Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina and the flooding that followed brought international attention to Louisiana.

This entry is 8th Grade level View Full Entry

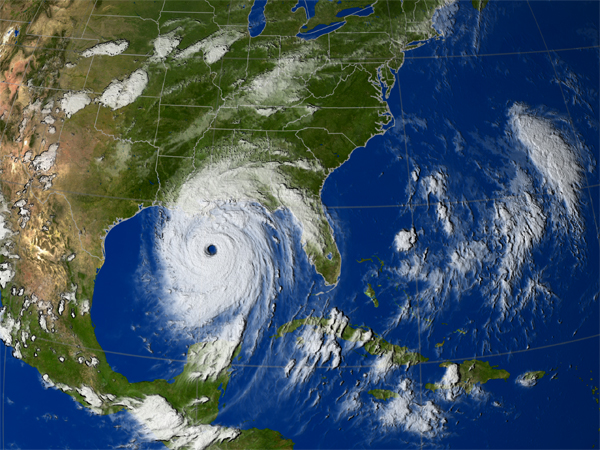

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

Hurricane Katrina clouds on August 29, 2005.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina came ashore near the border between Mississippi and Louisiana. It was the most destructive and costly disaster in US history. Louisiana recorded 1,577 deaths from the storm. Hurricane Katrina and the flooding that followed brought international attention to Louisiana. It also brought much debate about how well local, state, and federal officials prepared for and responded to the storm.

Why did Hurricane Katrina cause so much damage?

Hurricane Katrina made landfall near Buras in Plaquemines Parish at 6 a.m. on August 29 as a Category 3 hurricane. (Weather forecasters classify hurricane strength on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the strongest.) At landfall Katrina’s maximum winds were about 125 mph. Shortly before landfall, Katrina was moving at 12 mph, a relatively slow speed for hurricanes. A slow-moving storm, however, can be more destructive than one that moves quickly. At 5 a.m., the US Army Corps of Engineers received a report that the 17th Street Canal levee in New Orleans was overflowing. At 8:14 a.m. the Industrial Canal was breached, flooding New Orleans’s Lower Ninth Ward neighborhood. By 4 p.m. the London Avenue Canal levees broke as well, leaving approximately 80 percent of the city underwater.

In addition to damage in New Orleans, Katrina caused severe destruction along the Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas. In Louisiana the storm destroyed nearly every building in lower Plaquemines Parish. A massive storm surge sent water over the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet and the Industrial Canal in St. Bernard Parish, submerging 95 percent of the parish. More than forty thousand homes in St. Tammany Parish were damaged, including almost twenty thousand by flooding. Katrina also caused power outages in 1.1 million homes and other buildings in Louisiana and Mississippi. As a result of the storm, eight Louisiana oil refineries were forced to shut down. They accounted for 8 percent of US refining capacity.

How did people evacuate before and immediately after Katrina?

In preparation for the storm, officials in Plaquemines and St. Charles Parishes declared a mandatory evacuation on August 27, 2005. New Orleans Mayor Ray Nagin and Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco held a press conference the same day. Nagin declared a state of emergency in New Orleans but did not order a mandatory evacuation until August 28. A contraflow system, where all lanes of traffic flow in one direction, was used for the evacuation.

A total of 1.2 million people evacuated before Katrina hit, 92 percent of the affected population. Despite the evacuation order, approximately one hundred thousand people remained in the city as the hurricane came ashore, many because they didn’t have transportation.

Before the storm hit, the city opened the New Orleans Superdome as a shelter of last resort. By August 31 about twenty-six thousand people had filled the Superdome, which didn’t have enough food, electricity, or restrooms to accommodate everyone. The Ernest J. Morial Convention Center was also occupied by stranded evacuees. Around twenty-five thousand evacuees crowded the center, which also lacked food and accommodations. Some evacuees were moved to Houston’s Astrodome, which was opened as a shelter shortly after the storm. The occupants of the Superdome and convention center were not fully evacuated out of the city until September 3.

An estimated four thousand people were stranded on the Interstate 10 overpass in New Orleans, and others were stranded on the roofs of their homes, surrounded by floodwaters. In addition, hundreds of hospital staff and patients were stranded, and all but one of the hospitals was without power. It was hard to treat the patients because of a shortage of supplies. More than three thousand patients were evacuated by air from the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport in the week following the storm. This was the largest air evacuation of its kind in history.

How did the federal and state government respond to Hurricane Katrina?

Hurricane Katrina greatly disrupted communications. New Orleans Police Department officers and staff were unable to communicate with each other due to the destruction of radio towers and cell phone towers. Reports of looting were widespread. After the storm thirteen thousand National Guard troops arrived, and President George W. Bush deployed seven thousand active-duty troops to the Gulf Coast. Many complained that the troops hadn’t arrived quickly enough. In September Bush gave a televised speech at Jackson Square in New Orleans, describing the city as “nearly empty, still partly underwater, and waiting for life and hope to return.” The president pledged, “We will stay as long as it takes to help citizens rebuild their communities and their lives.” Some world leaders visited New Orleans in the weeks after Katrina, including King Abdullah of Jordan and Prince Charles of England and his wife Camilla.

On September 24 Hurricane Rita made landfall along the Louisiana-Texas border, complicating evacuation and recovery efforts. Like Katrina, Rita came ashore as a Category 3 storm. Five people died during the storm, and Rita caused significant property damage along the coast of southwest Louisiana and Texas. Despite the setback New Orleans was reopened on September 30, allowing evacuees who were able to return to see what was left of their homes.

Through various pieces of legislation, the federal government provided $71.5 billion to Louisiana to help rebuild after Katrina and Rita. In addition, more than 1.1 million Americans volunteered to help with recovery efforts, gutting and rebuilding houses, serving meals, and more. After Katrina and Rita Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco created the Louisiana Recovery Authority (LRA). According to the LRA, the two storms caused $75–100 billion in property damage. Debris from demolition and renovation of damaged property in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina was estimated to be one hundred million cubic yards—enough debris to fill more than eight million dump trucks. Katrina also caused the largest insurance loss in US history, with $41.1 billion paid out on more than 1.7 million claims. Claims in Louisiana accounted for 63 percent of those losses.

What were the long-term effects of Hurricane Katrina?

State, local, and federal officials blamed each other for delays in the evacuation. Michael Brown, head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), resigned after widespread criticism of the federal response to Katrina. He was replaced by David Paulison, who promised to improve the agency. Criticism of the Bush administration’s Katrina response continued, affecting the 2008 presidential race, which wasn’t the only major race affected by Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. Governor Blanco announced on March 20, 2007, that she wouldn’t run for a second term after being criticized for the state’s response and recovery efforts.

Katrina also caused a public debate about the failure of New Orleans’s levees. Local levee boards and the US Army Corps of Engineers manage the levee system. In 2006 Blanco signed a law to combine the levee boards and simplify management. That same year the US Army Corps of Engineers, which designed the levees, acknowledged in a report that levee design flaws caused most of Hurricane Katrina’s flooding.

The long-term effects of the storm on the state’s population are still unclear. Katrina forced 1.2 million Louisianans to evacuate, with some displaced for months or years. Thousands of evacuees ended up in other states, and some chose to resettle permanently. By 2020 New Orleans had regained about 79 percent of its pre-Katrina population. Hurricane Katrina also sparked interest in restoring Louisiana’s barrier islands and wetlands to help protect it from future hurricanes. In 2009 President Barack Obama created a federal task force to coordinate restoration of the Louisiana and Mississippi coastlines. Katrina’s destruction of the state’s wetlands led to more efforts to protect these natural resources, which were already in danger before the storm. Immediately following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in late 2005, the Louisiana Legislature created the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA), a single state authority, to oversee coastal restoration and hurricane protection activities and funding in the state. Authorized by the US Congress in 2006 to handle federal funding as well as state funding, CPRA was responsible for creating the first Comprehensive Coastal Master Plan for Louisiana in April 2007. The master plan, which is revised and reissued every five years, is intended to provide a template for coastal protection and restoration work in Louisiana for a five-year period. Since CPRA’s creation, a variety of coastal restoration projects have taken place across South Louisiana.