Nathan Abshire

Nathan Abshire was a singer, instrumentalist, and songwriter who was a central figure in the mid-twentieth-century evolution of Cajun music.

PINE GROVE PRESS

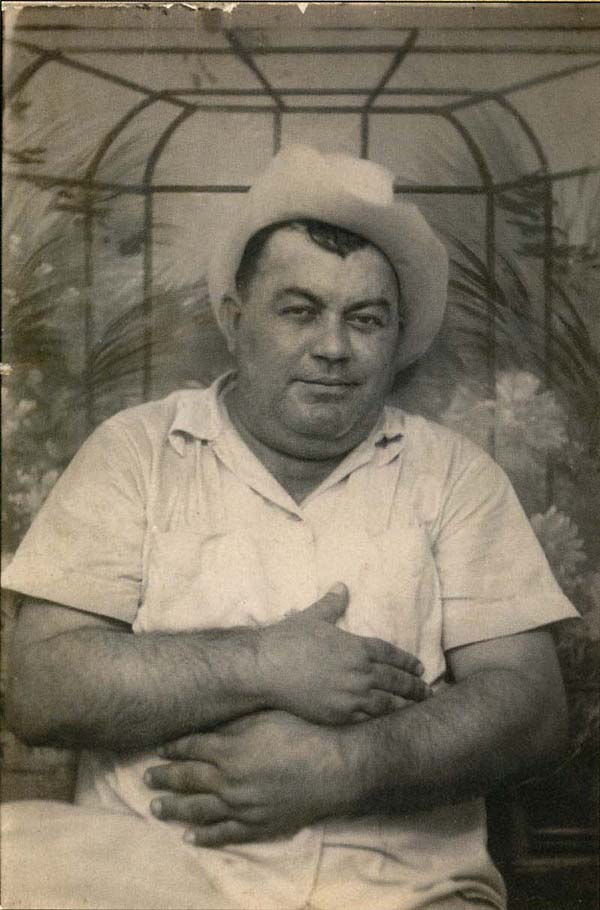

Nathan Abshire.

A central figure in the mid-twentieth-century evolution of Cajun music, Nathan Abshire was a singer, instrumentalist, and songwriter who vividly embodied the working-class origins of traditional Cajun music. While he mirrored the midcentury infatuation with country-flavored honky-tonk music—fiddle-driven and slide guitar-embellished—Abshire later helped lead a resurgence of more traditionally crafted Cajun music with the sound of the old-time button accordion reinstalled at its center. This was the music that had fueled both bals des maisons (house parties) and fais do-dos (weekend dances) in the old days. Rural Cajuns often listened to and played this music after work on their front porches, hence its historical categorization as “porch music.” Abshire’s performing and recording career playing “porch music” spanned six decades, starting in the 1920s. Although he enjoyed periods of great popularity, he was seldom able to rely solely on his music making to earn a living, working at manual labor jobs most of his life.

After World War II, Abshire and his wife, Olla Boudreaux Abshire, settled in the rural town of Basile, where he regularly worked in local music clubs and became caretaker of the town landfill. Around the same time, he became a celebrated figure of Cajun music’s rural origins. Abshire’s existence during the second half of his life centered around both his deep attachment to Cajun music and the modest pleasures of a life lived on the fringes of bleak poverty. As Cajun folklorist and historian Barry Ancelet explained in a profile written three years after Abshire’s death in 1981, “It was distressing to see such a great artist give himself so completely to his society all his life without adequate financial return, but one was hard-pressed to describe Nathan as a poor man when his over-sized heart and spirit were taken into account… Nathan’s bluesy music expressed his emotional personality, as full of soulful pathos as exuberant joy… [And in Basile,] his front yard became an extension of his job as he collected used objects of interest to sell, and his front porch became a cultural salon, where he held forth daily on Cajun music.”

A Deep Attachment to Homemade Music

Abshire was the eldest of six children raised by Lennis (sometimes spelled Lanas) Abshire and his wife outside the town of Gueydan, bordered on one side by saltwater marshes and on the other by the Bayou Queue de Tortue. Both parents played accordion, as did an uncle who lived with the family. The uncle had a new, expensive accordion, and as a boy, Abshire’s desire to play it was great. As he told Ancelet, “I learned to play by myself. No one taught me… I was six years old. I started playing on an accordion that cost three-and-a-half dollars. It wasn’t mine. It was one of my uncle’s. He lived at home and there was this little old armoire, but there were these marks that he would put in between, and I didn’t know that. I couldn’t see those marks, and when he left to go to work, I’d get to play. When he’d come back at noon, he’d take off his belt, Jack… He’d give me a licking, and he really could whip! Listen! But I never gave up. At noon, he’d leave again and I’d grab it again. At night, when he came back home, he’d check it again. When it wasn’t in the same place, he’d give me another licking. Then he gave up and finally gave it me.”

By the age of eight Abshire was playing professionally in local clubs, at bals des maisons, and at fais do-dos. During his apprenticeship and early training, he eventually played with and learned from two legendary Creole and Cajun musicians, the extremely influential accordionist Amédé Ardoin and his sometime accompanist, fiddler Lionel Leleux.

The Invasion of Western Swing

By the time he reached his early twenties, Abshire was recruited by one of the most popular bands in the region, Happy Fats and His Rayne-Bo Ramblers, led by guitarist Leroy “Happy Fats” LeBlanc. In 1935, the band traveled to New Orleans for a Bluebird/RCA recording session split with another of the region’s most popular bands, The Hackberry Ramblers. Abshire was featured on four of the Rayne-Bo Ramblers tracks, but the sound of his accordion was already becoming obsolete as vernacular music in south Louisiana was being heavily influenced by western swing, with an emphasis on slide guitars and fiddle solos. The oil industry boom along the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast was quickly changing the region’s demography. Out of favor was what incoming Anglos described as “chank-a-chank” music; they preferred the more modern sounds of western swing, embodied by Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, and they wanted to hear slick dance arrangements driven by a slide guitar, featuring solos on the fiddle.

The following decade and a half were difficult for Abshire. He tried his hand at playing western swing on the fiddle with only moderate success. The US Army drafted him in 1942, but it soon became clear that his illiteracy and tentative grasp of the English language made him less than the most desirable inductee. Following a training accident in which his leg was broken, the Army shipped him back home. After the war, he worked at a sawmill until an accident there set him to work repairing oil-fired stoves, a service that likely was not in great demand. But then his fortunes changed almost overnight. Returning Cajun military personnel wanted to hear some of that old-time “chank-a-chank” music, and so did most of the Cajun populace. The return of the sound of the accordion is generally credited to another talented “country boy”—Iry Lejeune, a tragic figure who died at the height of fame in a late-night car accident returning from a gig in 1955. By the mid-1950s, Nathan Abshire had established his own career, which would see him through the next three decades.

Flourishing in the Cajun Revival

Following a postwar period in which old Cajuns and newly arrived Anglos employed in south Louisiana’s booming oil industry both grew more familiar with Cajun culture, and especially old-time Cajun music in dance halls and on the radio, the music revival turned into a passionate civil-rights movement as Cajuns began to take pride in their culture after decades of discrimination. Efforts to revive interest in the Cajun identity, including the use of Louisiana French, began in the 1960s, led in part by musician Dewey Balfa. And at his side much of the time was Abshire, who recorded frequently, appeared on college campuses and at festivals—including the vaunted Newport Folk Festival in 1967 with the Balfa Brothers—and was asked to be part of several film documentaries made in the 1970s.

Abshire’s best-known tune was “Pine Grove Blues,” his first hit, recorded in 1949 and re-recorded many times. But it was more than one song, or even music itself, that ennobled the life of Nathan Abshire—it was his embodiment of a rural culture frequently looked down on, but fierce and proud in its own way. Abshire and Balfa frequently played music together—they had come from similar backgrounds and knew much of the same music. But Balfa made his living in town as a school bus driver and insurance salesman, someone adept at socializing, making small talk, reading social cues. Nathan Abshire was a country boy, and his music encompassed most of what he had to say. It had never really been an easy life for him, he reflected toward the end, but he was proud of his accomplishments: “A musician’s life is hard, about as hard as a man can have it,” he told Barry Ancelet. “Walking up to three miles to make three dollars… But you could go to the store back then and you couldn’t bring back everything you bought there all by yourself. You used to get something for your money.”