Ishak Indigenous People

The Ishak are an Indigenous people who have lived in southwest Louisiana and southeastern Texas since precolonial times.

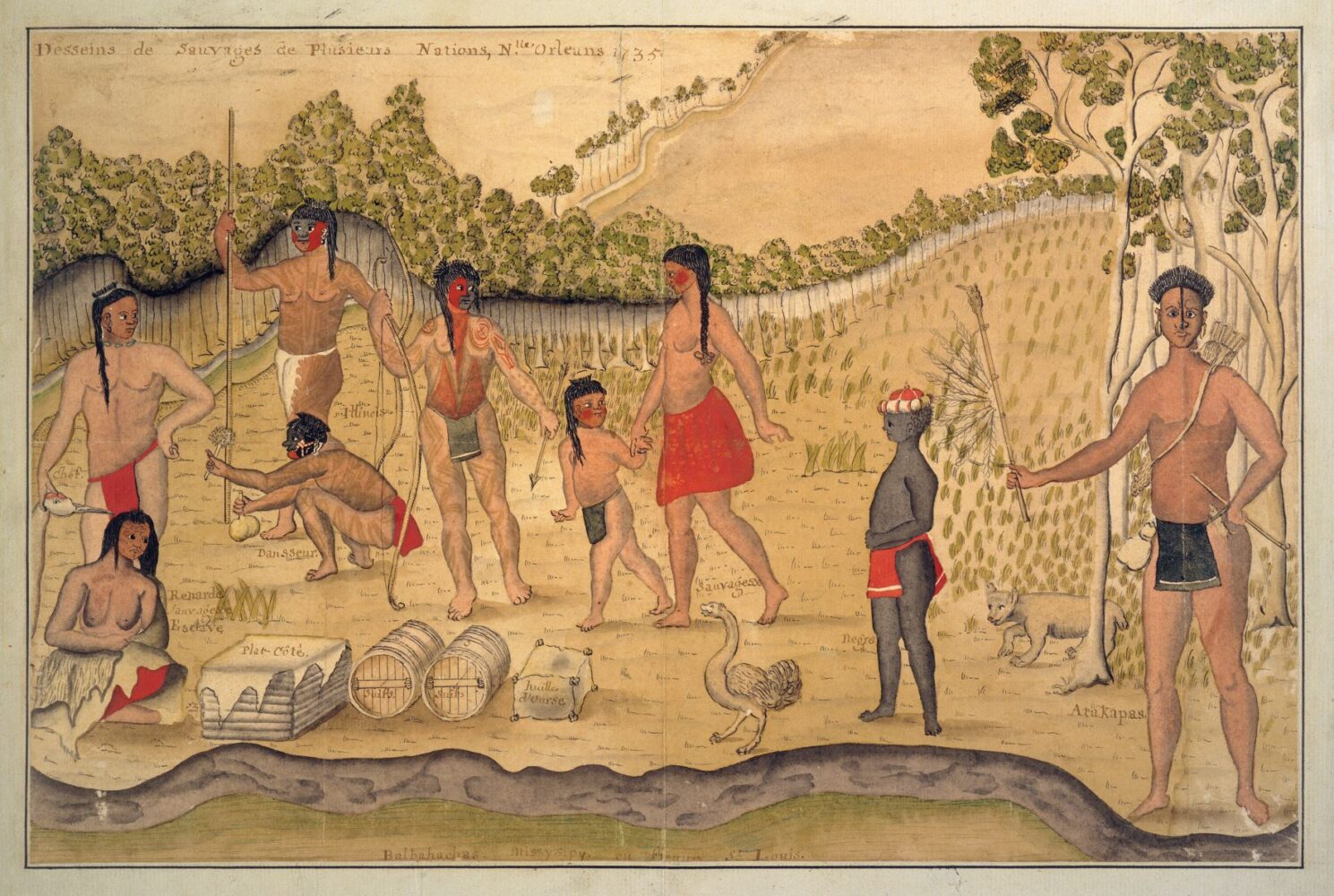

Gift of the Estate of Belle J. Bushnell, 1941. Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

An illustration by Alexander de Batz depicts eight Indigenous people and one boy of African descent. One of the individuals is an Ishak person wearing a feather headdress, sporting facial tattoos, and carrying a calumet, a ceremonial pipe.

The Ishak are an Indigenous people who have lived in southwest Louisiana and southeast Texas since precolonial times, with traditional lands stretching from Vermilion Bay to Galveston Bay. Various organized groups of Ishak exist currently, and while federal agencies have documented the Ishak in the past, no current Ishak groups enjoy federal recognition. Many Louisiana Creoles have Ishak ancestry, causing the group to be known sometimes as “Creole Indians.” The tribe has had a lasting influence on zydeco music, and its language is undergoing a resurgence.

Naming

The self-designated name for this group of Indigenous people is “the Ishak,” a name that approximately means “human beings” or “people,” but it may be related etymologically to the concept of birth, as in “those who have been born.” The Ishak are also known by the Choctaw exonym hattak apa—meaning “man eaters”—which was carried over into European languages as “Atakapa” with various spellings. That name has often been used deliberately and incorrectly in centuries past, especially as a slur to dehumanize the Ishak. While the Choctaw’s name refers to cannibalism, evidence of actual cannibalism amongst the Ishak is dubious at best and slanderous at worst. The name “Atakapa” likely didn’t refer to actual cannibalism. Historian Elizabeth Ellis points out that “man eater” was a metaphor for someone who would take another into slavery during the early colonial period in Louisiana. As such, it was likely the specter of being enslaved by the Ishak in battle that caused some tribal neighbors to use the term. It was later picked up by colonists as a justification for cruel treatment toward the Ishak.

During a reorganization of Ishak people in 1996 under the late Chief Hubert Singleton, the name “Atakapa-Ishak” was chosen for what is perhaps the largest current group of Ishak, the Atakapa-Ishak Nation of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. Other organized groups of Ishak people include the Attakapas Opelousas Prairie Tribe as well as the members of the Grand Bayou Indian Village in Plaquemines Parish, the latter being a geographic outlier. Other historically related peoples include the Opelousas as well as the Akokisas and Bidais of Texas.

Traditional Lands

In precolonial times, the Ishak lived in territory stretching from what is now known as Vermilion Bay in Louisiana to as far as what is now known as Galveston Bay in Texas. This territory included areas such as Lake Charles, Lafayette, St. Martinville, and Carencro, places where Ishak people still live now. Some of the traditional Ishak areas were named the Attakapas Parish of the Orleans Territory by the United States after the Louisiana Purchase, a continuation of the French practice.

Early Contact with Europeans

The Ishak are likely the Han People who rescued the shipwrecked Cabeza de Vaca in 1528. Based on his documentation, this means the Ishak were among the first of many Indigenous nations for whom colonizers noticed both the cultural acceptance of transgender people and marriages that were not heterosexual. Alexandre de Batz’s 1735 painting Desseins de Sauvages de Plusieurs Nations contains an image of an Ishak person wearing a feather headdress, sporting facial tattoos, and carrying a calumet, a ceremonial pipe. Ishak on a bison hunt were encountered by French memoirist Louis Milford in the late 1700s.

Ethnic Identity

Due to a history of living in close proximity to African-descended people during times of slavery, segregation, and beyond, most contemporary Ishak People have African ancestry. Many also identify as Louisiana Creoles. One reason perhaps for a lack of recognition of the tribe is a prejudice against people who are of both African and Native American ancestry being recognized as Native. So many Louisiana Creoles have Ishak ancestry that the Ishak are sometimes colloquially known as “Creole Indians.” Ishak people today typically embrace their mixed identity.

The Arts

One Louisiana art form often associated with the Ishak is zydeco music. Not only do many zydeco musicians recognize their heritage in the tribe, but the geography of zydeco generally overlaps with traditional tribal lands. Some scholars, such as Rain Prud’homme-Cranford, have noticed traditional Gulf South Native American musical and dancing forms within zydeco culture. This heritage led Hubert Singleton to title his monograph about the Ishak, The Indians Who Gave Us Zydeco.

Contemporary Ishak poets and playwrights include Tanner Menard, Carolyn Dunn, Rain Prud’homme-Cranford, Andrew Jolivétte, and Jeffery U. Darensbourg. The works of all these writers focus in some way on mixed Indigenous identity.

Ishak baskets are preserved in several prominent museums, including the National Museum of the American Indian.

The Ishakkoy Language

The language of the Ishak is properly known as Ishakkoy, “Ishak talk,” or Yukhiti Kóy, “the talk of the sort of people we are.” It has been incorrectly known as Atakapan, in a way similar to the misnaming of the Ishak themselves. The language was described by Albert Gatschet and John R. Swanton of the Bureau of American Ethnology in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Contemporary linguist David V. Kaufman has both developed a new orthography of the language and published a revised and reorganized version of the Gatschet and Swanton dictionary, making the materials more accessible. A revised grammar of the language has been published by Geoffrey D. Kimball. Contemporary narratives in the language have been composed by tribal member Russell Reed based on these new materials. New poems and songs have been composed in Ishakkoy by Tanner Menard, Joseph B. Darensbourg, and Jeffery U. Darensbourg.