James Freret

Entry covers the life and work of New Orleans architect James Freret.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

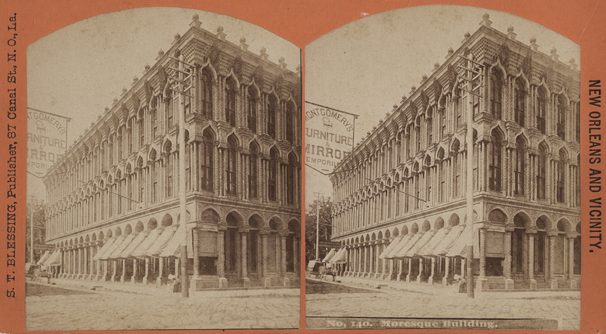

Moresque Building, New Orleans and Vicinity. Blessing, Samuel T. (photographer)

Trained before the Civil War in the ateliers of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, when few Americans had yet studied there, James Freret was the first native-born New Orleans architect to achieve national prominence in the profession. He excelled in ecclesiastical buildings, and built his reputation on projects for the Catholic Church throughout Louisiana and the deep South, few of which survive today. In many commercial and residential projects he was an early and skillful proponent of the contemporary Second Empire style. After his death in 1897, the American Architect and Building News praised him as “one of the most distinguished architects of the South.”

Early Life

Freret was born in 1838 to a prominent New Orleans family (his uncle, William, served as mayor in the 1840s), whose social connections later gave him access to important clients. His early architectural training in New Orleans (from 1857) was with George Purves, who had worked in London and New York, and his older cousin, William A. Freret, with whom he designed the Touro Alms House and the Moresque Building, two of the city’s largest Civil War-era building projects. The Moresque, unfinished until after the war, was the finest example of cast iron construction in New Orleans.

In 1860–61, Freret studied in Paris under Charles-Auguste Questel (1807–88) and traveled through France, England, and Italy. Surviving drawings from his study tour are evidence of a keen eye and a skilled sketch artist. Following the outbreak of the Civil War, Freret returned to Louisiana after taking a commission as an officer in the engineering corps of the Confederate Army. He worked on the fortifications at Port Hudson, where in June 1863 he was wounded in battle, taken prisoner briefly, and paroled.

Early Architectural Career

Launching an architectural practice in the war-shattered economy of New Orleans was difficult, and apart from several houses, many of his early projects were unrealized. In 1864 he entered into competition for St. Vincent Orphan Asylum on Magazine Street, which he lost to Thomas Mulligan, and he prepared proposals, also unsuccessful, for St. Joseph’s Church (1866), a new Masonic Hall (1867, 1868), and the Jewish Widows and Orphans Home (1869). In all of these early projects, he remained close to his Parisian training, and his color wash presentation drawings showed his mastery, in Beaux-Arts fashion, of many historicizing styles.

It was from the Jesuits in 1869 that Freret received his first important commissions. For the Jesuit Church of the Immaculate Conception (130 Baronne Street), he designed a high altar (fabricated in France in 1870), and for Spring Hill College, a Jesuit school in Mobile, Alabama, he designed a three-story brick administration building in a French Renaissance manner. He was again hired by the Jesuits in 1872 to design a chapel and tomb at St. Louis Cemetery I (near the intersection of Canal and Basin Streets), and in 1875 for the church of St. Charles Borromeo (174 Church Street) at Grand Coteau.

Freret’s earliest large-scale commercial success was the New Orleans Gas Light Company’s three-story office building, assertively Second Empire in style, on Baronne Street (1875). Other important commissions followed: St. Patrick’s Hall (1875); a catafalque of Pius IX for the Cathedral of New Orleans (1878); a building for Straight University, an African-American school on Canal Street (1878); and the Lemann Brothers Stores at 314 Mississippi Street in Donaldsonville. It was St. Patrick’s that cemented Freret’s reputation as one of the city’s most versatile designers. Occupying most of a block of Camp Street, St. Patrick’s was another bold statement in the Second Empire style. With this project, he had a major impact on the appearance of the city center at Lafayette Square, having also designed the Moresque Building opposite.

During the 1880s Freret was also changing the look of the commercial district. The Tchoupitoulas Street stores for C.H. Lawrence and Nicholas Burke, the Delgado Store on Customhouse Street, and the Dalsheimer & Company store on Canal Street were all completed in 1884–85. Also finished at this time were the Louisiana Sugar Exchange, on a riverfront triangle of land, and the Produce Exchange at 316 Magazine Street (extant), for which he designed a magnificent exchange hall illuminated by a glass rotunda. With the commodities exchange projects, Freret was at the height of his practice and in 1884–85 he completed an interior renovation of the Immaculate Conception Church (he had designed the Jesuit College building next door two years earlier); a convent for the Sisters of the Good Shepherd on Bienville Street, published in the American Architect and Building News (February 14, 1885); and two fine Second Empire residences, the George A. Lanaux house (still standing at 937 Esplanade Street) and a twenty-room mansion for Samuel B. McConnico at St. Charles and Peniston Streets. From the mid-1880s, only Thomas Sully, who had established a practice in New Orleans in 1882, challenged Freret as the preeminent architect in the city.

As a Beaux-Arts student, Freret assembled an inventory of historical details and styles that would serve him throughout his career, and which he supplemented as a mature designer by continued looking and sketching. On a trip to Chicago in 1883, for example, he sketched the work of Burnham and Root, in particular their Calumet Club and Chicago Club buildings. It was perhaps in response to the Chicago work that he designed his only building in the Romanesque style, a courthouse for Ascension Parish in Donaldsonville (1887–89). This project was soon followed by the Gothic Revival Masonic Hall of 1892 on St. Charles Avenue.

Church and Residential Architecture

Freret’s practice encompassed many building types, but ecclesiastical work formed the core of his practice. For several decades he executed the majority of large Catholic Church projects in New Orleans, several late in his career: the Sisters of the Sacred Heart convent on Dumaine Street (1893–94); the Discalced Carmelites chapel and convent at Rampart and Barracks Streets (1895); the Sacred Heart of Jesus church and convent on Canal Street (1895–897); and an academic building for the Congregation of the Holy Cross, at Reynes and Dauphine Streets (1896). His career portfolio of churches and convents (nearly all of them lost today) extended beyond New Orleans to Reserve, Jeanerette, Fairfield, Shreveport, Lobdell, New Iberia, and Lockport, Louisiana; Pascagoula, Scranton, and Bay St. Louis, Mississippi; Mobile, Alabama, and Augusta, Georgia. One of his surviving churches, and one of his finest designs, is Episcopal: the small gothic chapel of St. Mary in Franklin, Louisiana (1871–72).

As a designer of residences, Freret’s work ranged from modest cottages to mansard-roofed Garden District mansions; sixty-eight house projects are documented, at least forty-three with surviving drawings. His own house, which he renovated in 1885, stands at 2340 Constance Street. His house for Joseph Hernandez of 1868 (now at 1641 Amelia Street) used the Greek forms favored in antebellum New Orleans. He worked in a stick style for another early residence, for William McLellan on Washington Street (1868), and for a villa for Maunsell White, Jr., at Deer Range Plantation, and he designed a gothic cottage, extant, for Austin Rountree at 1421 Josephine Street (c. 1869). For Charles H. Adams, he designed a house on Second Street in the Queen Anne style, which was immensely popular for Uptown residences during the last decade of Freret’s career. His late renovation and addition for Judge Henry L. Lazarus (3519 Camp Street), which featured an opulent, wood-paneled interior and cupola, was published in American Architect and Building News (May 12, 1894).

Freret died of heart disease at age sixty on December 12, 1897, survived by his wife, Aline Allain, and seven children. He had no direct successor professionally, having partnered only once, briefly, at the beginning of his career (with Charles Crampon in 1867). His son-in-law Charles Allen Favrot (1866–1939), who had been his draftsman (1885–88), and Louis A. Livaudais (1870–1932), who had also worked for Freret until 1895, went into practice together under the firm name of Favrot and Livaudais, acquiring some of Freret’s clients after his death.