John McCrady

One of the best-known twentieth-century southern artists, John McCrady studied and worked in New Orleans, where he established an influential art school.

Courtesy of Ogden Museum of Southern Art

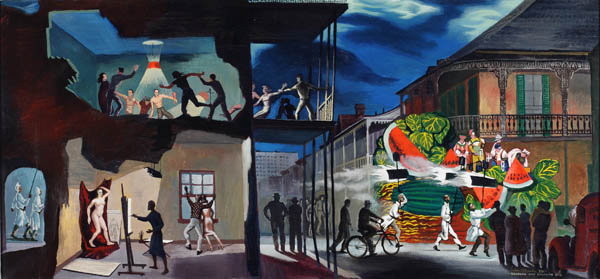

Parade. McCrady, John (artist)

One of the best-known twentieth-century southern artists, John McCrady studied and worked in New Orleans, where he established an influential art school. His scenes of the rural South are often compared with the work of Regionalist or American Scene painters such as John Steuart Curry, Grant Wood, and Thomas Hart Benton—the latter of whom McCrady studied with briefly. Like those artists, McCrady utilized images of everyday life in small-town and rural America for an iconic affect. While their work focused on the Midwest, however, he painted scenes of the American South and became particularly well-known for his images of southern African Americans.

Early Life and Career

Born in Canton, Mississippi, on September 11, 1911, McCrady was the son of an Episcopalian minister, Edward McCrady, and his wife, Mary Ormond Tucker. After briefly living in Greenwood, Mississippi, and Hammond, Louisiana, the family settled in Oxford, Mississippi, in 1928, where Edward McCrady taught philosophy at the University of Mississippi. At age twenty-one, John McCrady left Mississippi to study art at the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans School of Art. After just a year of classes, McCrady won a scholarship to the Art Students League of New York by submitting a portrait of an African American man. In New York, he studied under Kenneth Hays Miller and briefly with Thomas Hart Benton, both of whom proved influential. Benton’s sinewy anatomical style influenced McCrady’s work, while Miller introduced McCrady to a multistage technique used to paint oil transparencies over a tempera underpainting—a technique McCrady continued for the rest of his life.

Career Success and Recognition

After his study in New York, McCrady returned to the French Quarter and taught at the Arts and Crafts Club. Often depicting religious or rural scenes, his work emphasized contours and individuals in action. In addition to the Regionalists, McCrady was influenced by American artist Albert Pinkham Ryder, whose cloudy skies he sometimes emulated. In Woman Mounting a Horse, he makes direct reference to Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens, particularly in the fully developed female form and overall construction of the composition. Although McCrady decried the work of surrealist painters, his compositions sometimes merge dream and realism.

In 1935, McCrady’s work was included in Thirty-Five Painters of the Deep South, an important show at the well-respected Boyer Galleries in Philadelphia; subsequently the Boyer Galleries in New York featured McCrady in a one-man show. The New York exhibit included one of the artist’s best-known paintings, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot (1937). Inspired by the spiritual of the same named, the paining combines rural and religious themes in a night scene. Mourners hover over a deathbed visible through the open door of a cabin, while angels descend to take a newly departed soul to heaven in a chariot. The painting has often been compared with the writings of New Orleans author Roark Bradford, whose book Ole’ Man Adam and His Chillun inspired Marc Connelly’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play Green Pastures.

In response to the exhibition of McCrady’s work, Time magazine called the artist “a star risen from the bayous” who would do for painting in the South what Faulkner was doing for literature. McCrady also received high acclaim in Newsweek and New Republic. Life published a five-page spread on the artist and commissioned him to paint the “the second in a series of dramatic scenes in twentieth century American history.” McCrady chose to paint the assassination of Huey Long and produced one of his best-known, and most controversial, artworks. In 1939 McCrady received a Guggenheim fellowship “to paint the life and faith of the southern Negro.”

Beginning in the late 1930s, McCrady was one of many artists executing murals and easel paintings for the Graphic Division of the War Services Office for the Works Progress Administration. In 1942 he designed a series of propaganda posters. He Gives 100%, one of his contributions, reveals McCrady’s expertise with contour drawings and expressive body gestures. His interest in the surreal and the suggestion of activity beyond the easily apparent is implied in This Happens When You Talk to Others About Ship Sailings. The contour of a dense cloud of black smoke takes on its own life above the sinister shape of the conning tower of an enemy ship.

Later Career

After the war, McCrady refocused his interest on the South. His painting Robert E. Lee and Natchez depicts the historic 1870 steamboat race, during which the captain of the Robert E. Lee stripped the vessel of millwork and all unnecessary weight. In Boys Playing, children play games from the 1880s, including leapfrog and Jack-in-the-saddle. Rosalie Plantation sits on the bluff above Natchez-Under-The-Hill and the steamboat dock, while thick black smoke appears like a solidified human form.

In 1942, McCrady opened the John McCrady School of Art in New Orleans’s French Quarter. Overseen by McCrady and his wife Mary Basso McCrady (the sister of writer Hamilton Basso), the school flourished for more than three decades. Henry Casselli, Alan Raymond Flattman, Rolland Harve Golden, and Ida Kohlmeyer were among its most successful students. Also during the 1940s, McCrady illustrated Hodding Carter’s books, The Lower Mississippi (1942) and Floodcrest (1947) and provided illustrations for Mardi Gras Day (1948).

In 1946, McCrady’s work was exhibited at the Associated American Artists Gallery in New York. While most of the reviews were favorable, a communist newspaper, The Daily Worker, denounced McCrady as a racial chauvinist. Stunned by the criticism, McCrady experienced a long period of soul-searching. For a decade, he allowed his teaching and writing to take precedence over his creative work. Between 1963 to 1968, however, McCrady increased his artistic production. He had just completed three murals for the Bank of Oxford in Oxford, Mississippi, when he died suddenly on December 24, 1968, at the age of fifty-seven. Only three weeks earlier, he had been diagnosed with cancer. His work, however, remains influential and is included in the collections of the Georgia Museum of Art, the Saint Louis Art Museum, and the Louisiana State Museum. The Historic New Orleans Collection maintains many of McCrady’s papers, as well as the records of the John McCrady School of Art.