Kate and Jean Gordon

Sisters Jean and Kate Gordon stand out as among the most influential women of the progressive era in New Orleans.

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

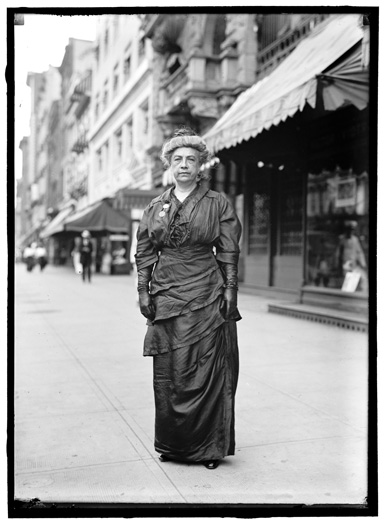

Kate Gordon. Harris & Ewing, photographer.

Sisters Jean and Kate Gordon stand out as among the most influential women of the progressive era in New Orleans. Though their interests often overlapped, they also carved out distinctive areas of individual influence: social welfare for Jean and woman suffrage for Kate. Together, they aroused a sense of social responsibility among women of their city’s middle class, fueling campaigns for many reforms in the city and state.

Jean and Kate Gordon were the daughters of Margaret and George Hume Gordon, the latter a transplanted Scot who emigrated from Edinburgh and married into a prominent New Orleans family. Jean was born May 27, 1867, while Kate was born July 14, 1861. They were educated in the city’s public schools and graduated from a local female academy. Never married, the sisters lived together in the family home, where a third sister, Fannie, kept house for them. They attended services at the First Unitarian Church and moved easily in the city’s circle of society.

Jean Gordon and the Reform of Child Labor Laws

It was younger sister, Jean, who first entered into civic affairs, beginning, after the death of her fiancé in 1888, with volunteer work for the Charity Organization Society. Exposure to the grim reality of child labor led her to begin a long crusade for revision of Louisiana’s ineffective labor laws. Working with the ERA Club (founded by her sister Kate), she produced a report on child labor in New Orleans and presented it to the legislature, but industrialists flocked to Baton Rouge to oppose any stronger regulatory measure. In Silk Stockings and Ballot Boxes, historian Pamela Tyler quotes Jean’s acerbic observation: “One, not knowing any better, would have been convinced that the most healthful, remunerative, educational place in the entire world in which to develop children was a mill or oyster cannery. One fairly tingled to spend the rest of life shucking oysters or peeling shrimp.” Having secured the backing of women whose husbands sat in the legislature, Gordon had expected female influence to work wonders; she was keenly disappointed when male legislators yielded to the industrialists’ arguments. After Gordon orchestrated more years of pleadings and heightened citizen pressure, the legislature at last acted in 1906 and passed the Child Labor Act, which provided for female factory inspectors. Jean Gordon herself became a factory inspector and served for five years, though at her own insistence, she was not paid a salary for her labors.

Her work soon revealed that the labor law’s provisions were inadequate. Undaunted, Jean Gordon studied stronger examples from other states, drafted an improved version, and persuaded a more compliant legislature to pass it in 1908. She had attained such prominence by the next year that Mayor Martin Behrman and Governor Jared Y. Sanders requested her assistance in promoting a southern governors’ conference to address the issue of child labor. The successful conference became an annual event. From her initial focus on child labor, Gordon went on to concerns with broader working conditions; she joined the National Consumers’ League, served as vice president 1909–1911, and organized the Louisiana branch in 1913.

Kate Gordon and the Fight for Woman Suffrage

Meanwhile, her sister Kate Gordon was garnering attention for her work for the more controversial reform of woman suffrage. Although an early member of Caroline Merrick’s Portia Club, she resigned in 1896 to establish the ERA Club, a less conservative body whose name stood for Equal Rights Association and whose members advocated votes for women. The 1898 constitutional convention in Louisiana, though impervious to appeals to include woman suffrage, had offered women a crumb when it gave property-owning, tax-paying women the right to vote on issues of taxation. Kate Gordon, president of her city’s Women’s League for Sewerage and Drainage, then prodded New Orleans to raise taxes to fund improvements to end the chronic flooding and epidemics attributable to poor sewerage and drainage. She spearheaded a petition campaign that forced the initiative onto the ballot, and then, anticipating that many women would feel reluctant to go to the polls, the Gordon sisters collected the proxies of some three hundred women and voted them on election day. When the measure carried, the local press credited the outcome to the women.

By the early twentieth century, Kate Gordon had become increasingly active in the National American Woman Suffrage Association, serving as corresponding secretary from 1901 to 1909. Her sister Jean was likewise an enthusiastic suffragist, having concluded, after her experiences with legislators, that women needed the ballot. After the failure of a child protective law, she had commented that “the much-boasted influence of the wife over the husband in matters political was one of the many theories which melt before the sun of experience….[women] realized how weak a weapon was influence and in that moment were sown the seeds of a belief in the potency of the ballot beyond that of ‘woman’s influence.’”

A confluence of factors contributed to a swelling of support for woman suffrage after 1910, and even in the arch-conservative South, suffrage sentiment grew. Yet southern suffragists could not unite on the question of an appropriate vehicle for accomplishing the cherished right to vote. Some favored an amendment to the U.S. Constitution, to accomplish the enfranchisement of all women simultaneously; others preferred amending each state’s constitution, thus preserving the state’s sacred right to regulate its elections without federal interference.

Kate Gordon ultimately became the most outspoken member of the states’ rights set of suffragists. As the most blatantly white supremacist of the suffragists, she made clear her view that federal control of voting requirements would lead to the reenfranchisement of African Americans in the South, thus undoing their disenfranchisement by measures designed by southern state legislatures to circumvent the Fifteenth Amendment. Almost all of the nationally prominent southern suffragists supported a federal amendment, but contrarian Kate Gordon insisted, “state sovereignty and white supremacy were inextricably connected.” She hoped that by instilling fear of a federal amendment, she could generate support for a state measure to enfranchise women.

Believing a federal suffrage amendment to be a threat to the southern way of life, in 1913, with money from millionaire suffragist Alva Belmont, Kate Gordon founded the Southern States’ Woman Suffrage Conference to press for woman suffrage by state action only. Though some New Orleans women affiliated, others formed a body called the Woman Suffrage Party to work with national suffragists for the federal amendment. While differing on tactics, this group also resented Gordon’s imperious ways and contentious personality. When Governor Ruffin Pleasant called for the adoption of a state suffrage amendment in 1918 and asked Kate Gordon to write a memorial to the legislature framing the issue, the New Orleans federal amendment supporters hoped to cooperate with her to lobby for passage. However, she coldly rebuffed them, presumably wishing to gain all the credit for adoption of a woman suffrage amendment to the state constitution. In this she was disappointed; the state legislature passed the measure, but the state’s voters defeated it. While the amendment won a majority of votes outside New Orleans, her own city’s voters provided the margin of defeat. In a seeming paradox, suffragists Kate and Jean Gordon then joined with the antisuffragists to defeat the federal amendment in Louisiana and later attempted, unsuccessfully, to block final ratification of the measure by Tennessee in 1920.

Civic Activism

The sisters contributed much to the civic betterment of their native city. Jean developed a keen interest in the situation of developmentally disabled girls and ultimately created the Alexander Milne Home for Girls, with both a detention home and a training center. She served as president of the board and supervisor of the home until her death and, for her service; she won the city’s prestigious Times-Picayune Loving Cup in 1921. She died in 1931 from complications arising from appendicitis.

Kate poured her efforts into the fight against tuberculosis, seeing success in 1926 with the opening of the New Orleans Anti-Tuberculosis Hospital, where she served as vice-president. She commented wryly to a friend, “In the community I am now known as Tuberculosis Gordon and Jean as Feeble-minded Gordon. Take your choice.” Upon her sister’s death, she also took over the management of the Milne Home. She died in 1932 of a cerebral hemorrhage.

Both women embraced a multitude of worthy causes during their civic careers in New Orleans. In addition to the projects discussed, they worked for establishment of a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, a Travelers’ Aid Society, a juvenile court, the New Orleans Hospital and Dispensary for Women and Children, a day nursery at Kingsley House, and the admission of women to the medical school of Tulane University. It is beyond question that Jean and Kate Gordon’s lives of activism made their city more livable and more humane.