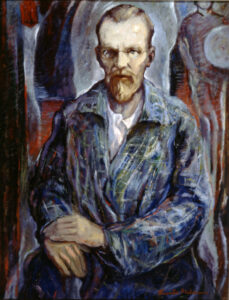

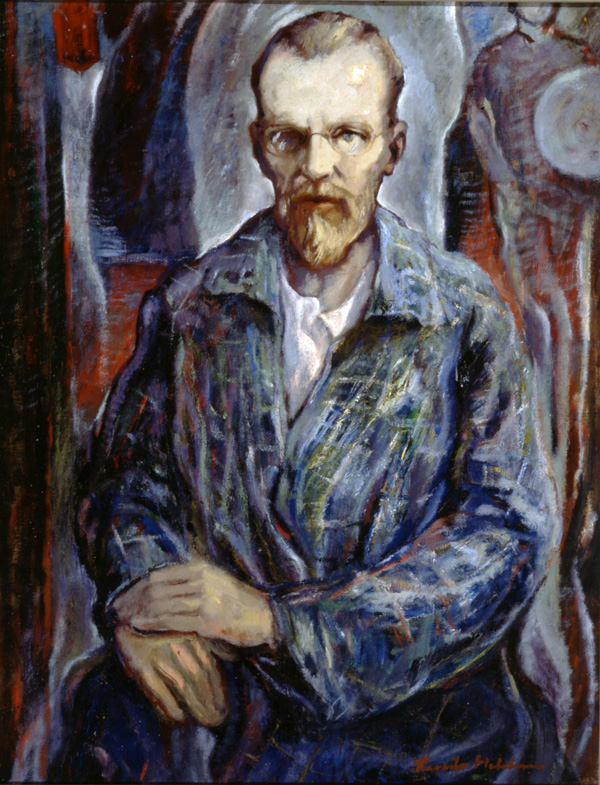

Knute Heldner

Swedish-born artist Knute Heldner emigrated to the United States where he split his time between Duluth, Minnesota and New Orleans.

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

Knute Heldner - Self portrait. Heldner, Knute (Artist)

Swedish-born Knute Heldner was among the best-known artists in New Orleans in the mid-twentieth century. With his blond beard, red velveteen trousers, blue shirt, and a cane he carried “for the jaunty look” it gave him, Heldner was very much at home in the bohemian art colony in the French Quarter in the 1920s through the 1940s. His impressionist painterly style set the standard for modern interpretations of the Louisiana landscape. Heldner also was the first to portray subjects of social realism in the French Quarter, instead of the merely picturesque largely favored by local artists.

Early Years

Born in 1877 in Verderslöv, a village in the province of Smaland, Sweden, Knute Heldner was raised on a small farm and received his early training at the Karlskrona Technical School and the National Royal Academy of Stockholm. An adventurous spirit, he became a naval cadet at the age of twelve and jumped ship while in his mid-twenties to come to the United States in 1902. He settled first in Wyoming and later in Minnesota. He found employment as a sheepherder, a Northwoods guide, lumber-camp cook, and cobbler—jobs that allowed him to pursue art courses at the Minneapolis School of Fine Arts in Minnesota and later the Student’s Art League in New York City. His artwork was first exhibited in 1915 at the Minnesota State Fair in St. Paul, where he won a gold medal.

In Duluth, Minnesota, Heldner began teaching at the small Rachel McFadden Art Studio, where he met student Colette Pope, who eventually became his wife. Heldner’s art from his earliest period is often introspective and philosophical, concerned with the hardships of the working man whom he witnessed in the mining and lumber camps of Minnesota. In one large composition, he painted himself as the camp cook in a snowy lumber camp in the Northwoods of Minnesota.

Career Development

By the time he arrived in New Orleans with his new young wife in 1923, Heldner was already nationally prominent. In 1926, he was invited to display his paintings in a one-man show at the Delgado Museum (now the New Orleans Museum of Art).

The Heldners traveled back and forth seasonally, from their summer home in Duluth to their winter home in New Orleans. Heldner won first place at the 1929 Chicago Art Show, which, combined with scholarship money from the city of Duluth, helped him finance a trip to Europe. It was a nostalgic return home and an opportunity to study and show his work in Paris, France, and Stockholm. Despite the European sabbatical, Heldner never varied his painting style, which he termed “post-impressionist.” His palette evolved, however, from dark tones to lighter, brighter colors after his exposure to the subtropical environment of New Orleans.

Returning to New Orleans from Europe, Heldner involved himself in the city’s art organizations. He was a charter member of the exclusively male New Orleans Art League, the 1927 offshoot of the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans, where he mounted an ambitious one-man show. As an art educator, philosopher, and writer, Heldner participated in the league’s art school, lecturing and teaching. He introduced a course in woodcarving, the art of his youth.

From 1931 to 1941, he completed a series of fifty dry-point etchings of the French Quarter. Unlike the customary scenes of monuments and colonial architecture found in the Vieux Carré, popularized by artists such as George Castleden, William Woodward, and Morris Henry Hobbs, Heldner’s etchings were studies of personalities in the Quarter and also of the poor and homeless during the Depression. These include Banjo Annie, depicting a woman slumped forlornly on a bench in Jackson Square; and The Bread Line, with a group of the hungry lined up like communicants before an altar.

Later Career

Heldner was employed by the Federal Art Project in Louisiana as part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s relief program for artists. Heldner helped collect hundreds of documents on artists, which resulted in a fifteen-volume fine arts and design encyclopedia, a project overseen by Ellsworth Woodward. Heldner continued to paint landscapes and portraits. To support his wife and two children, he was obliged to produce romantic paintings of the bayou, usually painted in heavy impasto with rich coloration. These bayou scenes, some hauntingly moonlit nocturnes, were immensely popular, and after his death in 1952, Colette Heldner, an artist in her own right, continued the tradition, painting her “swamp idylls,” as she called them, but in a more florid, expansive style.

Knute Heldner’s most significant paintings of this period are a series of large mural triptychs of agrarian life in the South, currently housed at Louisiana State University Art Museum: The Cotton Industry, The Sugar Industry, and The Turpentine Gatherers. In their scope and their stylized modernity of figures, these powerful paintings continued his interest in the workingman as an artistic subject and rank among the best of Southern regionalist art.

A philosopher by nature and deeply religious, Heldner also wrote unpublished plays and short stories, art instructions and critiques, as well as deeply felt essays in an attempt to reconcile the daily miseries of life and the horrors of World War II with a greater divine plan. His death at Charity Hospital in New Orleans in 1952 followed a particularly bleak two years of his life, during which Colette left him.

In the French Quarter, where flamboyant personalities often eclipsed true artistic talent, Heldner’s art has proved a steady light and inspiration for generations, influencing artists such as Robert M. Rucker, Steele Burden, and French Quarter artist Nestor Hippolyte Fruge. His paintings can be found at the Louisiana State University Museum of Art in Baton Rouge, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, and the Historic New Orleans Collection.