Les Cenelles

Les Cenelles is a groundbreaking collection of original French poems published by a group of free men of color in nineteenth-century Louisiana.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

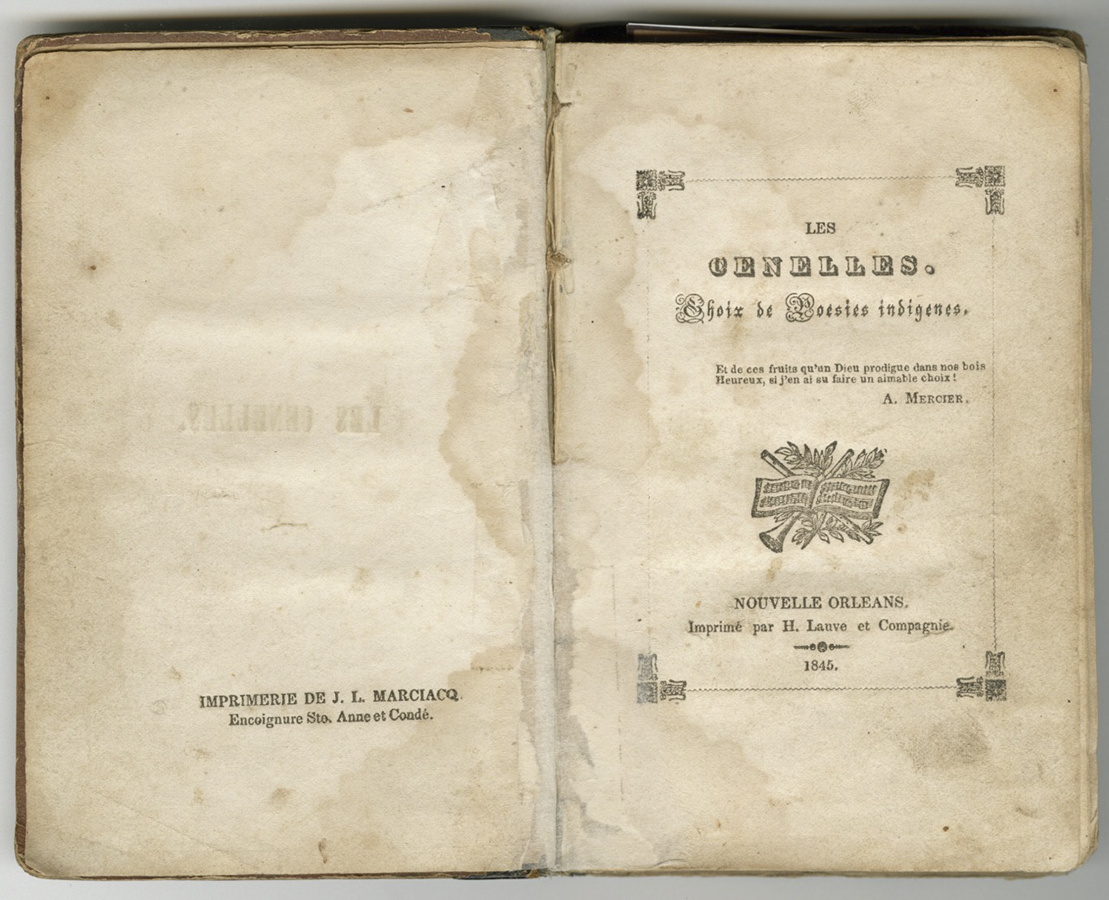

Frontspiece of "Les Cenelles: choix de poésies indigènes," published 1845.

In 1845 a group of free men of color published a collection of original poems in French entitled Les Cenelles: choix de poésies indigènes, known in English as Mayhaws: A Selection of Native Poetry. Under the editorial direction of Armand Lanusse (1812–1867), Les Cenelles brought together eighty-four works by seventeen different writers, most of whom lived in New Orleans. While the endeavor stands out as a landmark of Louisiana Creole culture, scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. also holds up the volume as “the first attempt to define a black canon” within US literature.

Free People of Color within Louisiana’s Francophone Literary Scene

Throughout the nineteenth century, Louisiana’s French-speaking community nourished a vibrant literary scene. Threatened by the increasing dominance of English, Francophone Creoles asserted their cultural identity through poetry, theater, short stories, and, after the Civil War, novels. Romanticism, the period’s main aesthetic current in Europe and across the Americas, encouraged authentic expression of the self and of regional characteristics. Moreover, many educated Louisiana Creoles, regardless of color, maintained ties with France. This movement blossomed in the 1840s, coinciding with a boom in the French-language press.

Despite their second-class treatment as a racial minority within the French-speaking population, Creole free people of color developed a rich community life and dynamic cultural institutions, especially in New Orleans. Many engaged in creative writing. Prior to the Civil War, social pressures and harsh legal restrictions obstructed any form of direct protest against racism and slavery. Case in point, a magazine founded in 1843, L’Album littéraire: Journal des jeunes gens, amateurs de littérature, ceased publication due to complaints about the radical stance of some texts. Not surprisingly, the poetry in Les Cenelles does not raise the issue of racial injustice—at least not overtly.

In his introductory essay Lanusse does address the benefits of education in the face of prejudice. This challenge spoke to the condition of free people of color as represented by the Creole poets of Les Cenelles. While some of the writers were teachers, including Lanusse, several others worked in trades like masonry (Auguste Populus), shoemaking (Jean Boisé), and cigar manufacturing (Nicol Riquet). Victor Séjour, on the other hand, had already emigrated to Paris, where he gained fame as a playwright. Two of the collection’s most important contributors, Camille Thierry (fourteen poems) and Pierre Dalcour (twelve poems), would later leave for France to escape racism.

Les Cenelles: What’s in a Name?

Les Cenelles is dedicated to “the fair sex of Louisiana,” i.e., Creole women, for whom Lanusse composes this laudatory quatrain:

Please do accept these modest Mayhaw Berries

That our heart presents to you in sincerity;

May a single glance received from your innocent eyes

Suffice for their glory and immortality.

Mayhaws, the fruit of the hawthorn bush (Crataegus opaca or aestivalis), are prized across the South for the jelly that can be made from them. In bygone days New Orleans youths often ventured to the swamps to forage for the berries, which they would bring to their mothers or their wives. Historian Jerah Johnson explains that the volume’s title “subtly and poetically evoked the image of small, uniquely flavored, and rare local delicacies that struggled for life in surroundings so hostile as to make the very gathering of them a dangerous travail, but one worth the risk because of the richness of the reward.” The mayhaw, or cenelle, thus served as a fitting metaphor for a literary project by Creoles of color.

Race, Gender, and Social Equality

By its very constitution Les Cenelles delivers a strong, albeit implicit, statement of intellectual equality and common humanity between white people and people of African descent. Drawing from the themes and tropes of Romanticism, the Creole writers place their feelings at the heart of their poetry. Many of their works are imbued with melancholy, loss, and a sense of alienation, all of which underscore the poets’ subjective authenticity. Moreover, their compositions display mastery of French versification—the rules for rhythm and rhyme in formal poetry—a highly esteemed skill in nineteenth-century intellectual culture.

Issues of racial identity emerge most clearly in relation to gender, specifically through the poets’ hopes and expectations regarding Creole women. Several poems exhort women readers and addressees to remain faithful in love and to shun material temptations. This concern for morality and sexual propriety speaks to anxieties about relationships between predatory white men and women of color. Armand Lanusse, the most represented writer in Les Cenelles with sixteen poems, addresses the matter very pointedly. In “Épigramme,” Lanusse satirizes the hypocritical piety of a Creole mother who wants to postpone her religious conversion until she can “place” her daughter with a rich man, presumably white.

A few poems do venture farther afield from the collection’s limited range of overall topics.

Taking a very French perspective, Victor Séjour’s “Le retour de Napoléon,” which had been previously printed in Paris, offers a nostalgic meditation on the supposed greatness of Napoleon I. In its celebration of the glory of France, the poem’s praise of the emperor comes across as strangely ironic given the latter’s attempt to revive slavery in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (where most of the poets had family roots) during the Haitian Revolution.

Visions of a Cultural Community

From its title page onward, Les Cenelles enacts various forms of belonging, setting community at the core of the collection’s vision for Creole poetics. One aspect of belonging involves the literary sphere, be it to Louisiana literature—such as by quoting white Creole writer Alfred Mercier—or to the realm of French belles-lettres by mentions of Victor Hugo, Alphonse de Lamartine, and, most especially, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, the most popular songwriter of the period. These authors’ works form a shared set of cultural references. More immediately, the Creole social milieu of New Orleans features prominently in many poems, namely through dedications to poets’ lovers and friends, some named, some anonymous. Finally, the performative nature of the texts themselves is foregrounded in notes indicating tunes for singing certain poems.

A telling example of attachment to community comes in B. Valcour’s “L’ouvrier louisianais” (“The Louisiana Worker”). Valcour bases his composition on a song by Béranger, borrowing from the French author the line, “Je suis du peuple ainsi que mes amours” (“I am of the people and so are my beloveds”). Confronted with the allure of exile to France, the Creole poet affirms his determination to stay in Louisiana:

As an unsung son of Orleans the New,

Despite her faults, I cherish her still;

To my country I wish to remain ever true…

Rosette and my home are my love’s only will.

Here, the “faults” attributed to the city reflect both racism and class prejudice, against which true love offers protection.

Influence and Critical Legacy

Les Cenelles enjoys recognition as a groundbreaking work of Black literature, notwithstanding the shifting nature of racial categories in nineteenth-century Louisiana. Its publication laid the foundation for more radical writings by people of color during the Reconstruction era and beyond. The Creole activist and historian Rodolphe Lucien Desdunes grants detailed treatment to the Les Cenelles and its contributors in his 1911 study Nos hommes et notre histoire (Our People and Our History). The collection later garnered serious critical attention from scholars as well as interpretations through tributes and performances. In 2003 Les Cenelles was republished in the original French by Éditions Tintamarre.