Longism

The term “Longism” refers to both the political machine and the radical populist doctrine established by Huey P. Long Jr. from the time he was elected governor in 1928 until about 1960.

This entry is 8th Grade level View Full Entry

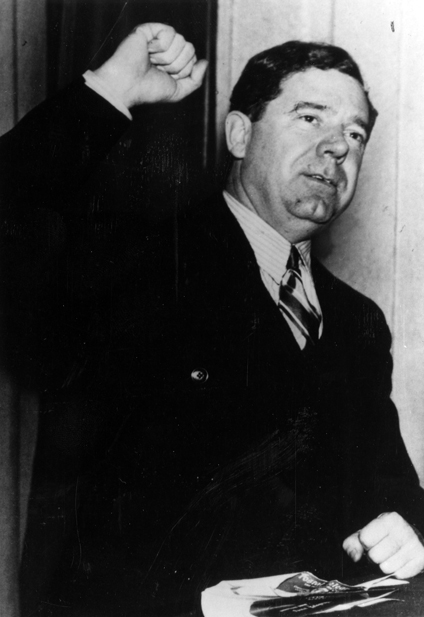

State Library of Louisiana

Huey Long during a Washington DC radio broadcast, 1935.

The term “Longism” refers to both the political machine and the radical populist doctrine established by Huey P. Long Jr. in Louisiana from the time he was elected governor in 1928 until about 1960, decades after his assassination in 1935. This lengthy period testifies to Long’s influence in a state where he achieved near-mythic status during his mere forty-two years of life. Long, both as Louisiana’s governor and as a US senator, identified himself as an advocate for the poor and developed policies to make their lives better and ensure their political support. After his death, he left behind a powerful and corrupt political legacy that contributed to Louisiana’s history. Many people would argue that Longism still has a strong influence on the state’s politics today.

How did Huey Long rise to power? How did Longism develop?

After Reconstruction, a corrupt alliance of conservative Democrats called the “Bourbons” and a group of New Orleans political bosses ruled the state government. Many Louisianans suffered extreme poverty in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and Louisiana lagged behind other southern states despite reforms enacted beginning in 1900. Long’s home territory, Winn Parish, nurtured a radical challenge to the status quo. A majority of Winn Parish voters voted socialist in 1912. Long knew that whoever could motivate the masses held real power, so he challenged the Bourbons’ unfair system.

Long began his political career in 1918, when he was elected railroad commissioner with the promise to lower freight rates for farmers. He used this position to enhance his reputation as a defender of the poor and opposed large oil and utility companies. In 1930, two years after he became governor, Long was elected to the US Senate, though he didn’t take office until 1932. He amassed extraordinary political power over the state with his fiery speeches. He promised thousands of poor Louisianans a better life, saying he’d make “every man a king” under his rule.

During the Great Depression Long implemented policies intended to improve the state’s infrastructure and the lives of his constituents, who were largely rural and poor. He authorized the construction of nine thousand miles of new roads and more than a hundred bridges. His administration also established public schools statewide, with free busing and textbooks, allowing thousands of children to attend school; approximately one hundred seventy-five thousand illiterate Louisianans attended night schools. State charity hospitals doubled in size, and the state university in Baton Rouge gained national recognition. Thousands of Louisianans could vote after Long eliminated the poll tax and pushed for a homestead property tax exemption. Over the course of his political career, voter participation in statewide elections more than doubled. Newly empowered citizens voted for the candidate who gave them new opportunities.

What problems or failures are associated with Long’s political career?

Although Long arguably did more for Louisiana than any politician before or since, his critics felt that his iron-fisted, dictatorial methods also damaged Louisiana’s politics. At the time of his death in 1935, he had gained more control over an American state than any politician in history. He built an unstoppable political machine by giving state jobs and government contracts to his loyalists and firing civil servants who opposed him. In addition to overseeing elections, he padded voting lists and oversaw ballot counting. Long also proposed a gag law suppressing criticism of his policies and started his own newspaper, Louisiana Progress, to attack established press outlets, many of which were critical of him. He used the state militia as his personal police force, declaring martial law in cities that didn’t comply with his wishes. He further made sure that his increasing power was unchecked by packing the courts with his cronies. Most blatantly, he dominated the state legislature, passing hundreds of bills that increased his power, destroyed his enemies, and stretched the limits of constitutionalism. Despite Long’s questionable tactics, Louisiana’s poor continued to support him strongly because he was opposed to the neglect they had suffered under Bourbon politics. The residents were either unaware of or unconcerned about Long’s ruthless political machine and the level of corruption in the state government; some even looked the other way as Long pocketed money. Because Louisiana was a one-party state at the time, the conflict between those who supported Long and those who opposed him split the Democratic Party in half. Long allowed no compromises, demanding absolute loyalty from his followers. If they opposed him, even in part, they became enemies, and he crushed them relentlessly. After foiling a 1929 impeachment attempt in Louisiana’s legislature, Long boasted, “I used to try to get things done by saying ‘please.’ Now I’m a dynamiter.” When Long was elected to the US Senate, he chose to leave the Senate seat empty and serve the remaining months of his term as governor. His hand-picked successor in the governor’s office was his longtime friend from Winnfield, Oscar “O. K.” Allen.

Long declared himself a presidential candidate after gaining millions of followers. During the Great Depression, he founded the Share Our Wealth Society in 1934 to redistribute the nation’s wealth. Under his plan each American family would receive a minimum income that would be funded by a progressive income tax. Long hoped to provide for the poor by capping the income of millionaires. According to Long, the Share Our Wealth Society had attracted seven million members in twenty-seven thousand clubs across the country within a year of its founding. Many historians have argued that this surge of enthusiasm for a rival presidential candidate drove Franklin D. Roosevelt to respond with the Second New Deal. This array of programs—including the Social Security Act, the Works Progress Administration, Aid to Dependent Children, and the Wealth Tax Act of 1935—was designed to ease the suffering of the millions of Americans affected by the Great Depression.

What lasting impact did Long have on Louisiana?

In September 1935 Long was killed in the Louisiana State Capitol—either through an assassination by Dr. Carl Weiss, the son-in-law of a state district judge, whose district Long had been manipulating, or from retaliatory bullets fired by his own bodyguards. For three decades following Long’s death, the Louisiana political arena was a battle between Longism and anti-Longism. The four governors who served immediately after Long’s death shared his political philosophy. Long’s personally chosen successor O. K. Allen won election to Long’s Senate seat but died in 1936 while still governor. James A. Noe, a Share Our Wealth enthusiast, then served as interim governor and appointed Long’s widow Rose McConnell Long to fill the vacant US Senate seat. Richard W. Leche, another Long insider, was elected governor in 1936 and served until a corruption scandal forced him to step down in 1939. His replacement was then-Lieutenant Governor Earl K. Long, Huey Long’s brother. Across the state other patrons of the Long machine won political office, including Robert Maestri, who served as New Orleans mayor from 1936 to 1946.

Louisiana was run by Long’s followers with a tight grip—less ruthlessly but more corruptly. Road construction, free textbooks, hospital expansions, and school expansions were still an important part of the political agenda, but more radical wealth distribution and social programs were generally abandoned. By making deals with Long’s former enemies, Long’s successors ceased attacks on the oil industry and granted tax exemptions to business and industry. They also enacted a regressive sales tax.

Governor Leche—who once said, “When I took the oath of office, I didn’t take any vow of poverty”—resigned in 1939, when federal authorities indicted him and several of his cronies for misusing New Deal funds. Another convicted Longite was Louisiana State University President James M. Smith, who embezzled half a million dollars of university funds.

When Leche resigned, Lieutenant Governor Earl Long became governor, serving until 1940, and he was later elected to two nonconsecutive terms from 1948 to 1952 and 1956 to 1960. Almost as notorious as his older brother, Earl Long imprinted his own brand of Longism on Louisiana. A clever politician, he recognized the potential voting power of excluded African Americans. While not attempting to dismantle Jim Crow laws, he eased many government restrictions, allowing a considerable number of African Americans to vote. Earl Long also convinced the legislature to equalize teacher pay between the races. He called for full voting rights for Black Americans in 1959 after legislation attempted to restrict Black suffrage. That same year he was committed to a state mental asylum by his family, but Long, still governor, ordered his own release.

In 1960 Earl Long was elected to the US House of Representatives but died before taking office, marking the end of a political era. Longism had already suffered several major defeats before Earl Long’s death. In 1940 anti-Long reformist Sam Houston Jones defeated Earl Long for governor; four years later, popular singer Jimmie Davis defeated Lewis L. Morgan, the candidate supported by Earl Long and Robert Maestri. In 1948 Russell B. Long, son of Huey Long, was elected to the US Senate, where he served until 1987. Russell Long chaired the Senate Finance Committee from 1966 to 1981 and influenced tax, Social Security, and welfare programs in the country. Like his father Russell Long advocated for a heavier tax burden for the wealthy. By the 1960s, with the exit of Earl Long from politics, Longism was no longer a powerful political force in Louisiana, but traces of its power remained. The Long name continued to capture votes, especially in rural parishes, all the way into the twenty-first century.

Former governor Edwin W. Edwards perhaps best exemplified a modern-day version of Longism. Through his liberal political views and charming personality, he cast himself as a Louisiana populist in the tradition of Huey and Earl Long. Edwards was elected to the US House of Representatives, serving from 1965 to 1972. While in Congress, he was one of few southern congressmen to support the extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Serving an unprecedented four terms as governor (two terms spanning 1972 to 1980 as well as reelections in 1983 and 1991), Edwards used windfall tax revenues from the oil industry to increase health and human services programs, create vocational-technical schools, and strengthen higher education.

Like Huey and Earl Long, however, Edwards frequently faced charges of corruption, especially when Louisiana reintroduced legalized gambling. He survived two dozen corruption investigations and remained enormously popular. During Edwards’s gubernatorial campaign against white supremacist and former Ku Klux Klansman David Duke, supporters printed bumper stickers saying, “Vote for the Crook. It’s Important,” and the voters did. Edwards’s luck finally ran out, however, in 2001, when he was convicted of extorting money from casino boat owners seeking licenses. A federal court convicted him on seventeen counts, including racketeering, money laundering, and wire fraud.