Louisiana Purchase and Territorial Louisiana

This entry covers the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 and the period of territorial governance that followed until Louisiana became a state in 1812.

This entry is 7th Grade level View Full Entry

The Historic New Orleans Collection

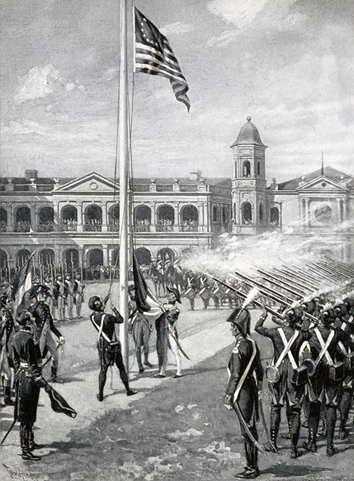

Jackson Square after the transfer of Louisiana from France to the United States in 1803.

The years 1803 to 1812 marked a turning point in Louisiana history. These years saw Louisiana’s transition from a European colony to a federal territory and then to the eighteenth US state. During this time Louisianans experienced social unrest, racial revolt, and even became involved in an international conflict.

What challenges did the Louisiana Purchase present to President Thomas Jefferson and Congress?

Nothing reflected the chaos and uncertainty of early Louisiana more clearly than the battle over its borders. In April 1803 France sold a vast but vaguely defined area to the United States through the Louisiana Purchase. News of the deal came as a surprise to the people of the United States. President Thomas Jefferson had sought to secure only New Orleans and access to the Gulf Coast. He now faced the challenges of governing far more territory and a larger, more diverse population. The Louisiana Purchase treaty also failed to specify clear borders. It would be almost two decades before the United States had clear title to, or legal ownership of, all the land that constitutes present-day Louisiana.

The boundaries of Louisiana took shape as a result of the political conflicts that gripped Europe and stretched across the Atlantic Ocean. These conflicts played out differently in North America, as the United States took advantage of Napoleon’s invasion of Spain in 1807 and the resulting crisis within the Spanish empire to seize West Florida in 1810.

As these international conflicts were going on, the federal government faced an equally difficult domestic challenge: how to govern the people in territory acquired through the purchase. The federal government began by subdividing the Louisiana Purchase into smaller, more manageable pieces. In 1804 Congress created the Territory of Orleans, which included most of what is present-day Louisiana. From 1804 until 1812 Louisiana existed under territorial rule. During this time federal leadership in Washington appointed most major offices, like the governor and judges, while local residents elected a territorial legislature. The territorial period ended when Louisiana became a state on April 30, 1812.

What tensions existed between the French-speaking population and the newly arrived Anglo-Americans in Louisiana?

Many white Louisianans actively sought statehood, and they believed that the territorial process was taking too long. They wanted to increase the number of elected offices and elect members of the existing French-speaking community rather than newly arrived Anglo-Americans. Although Louisianans had grievances such as these, few sought a return to European rule, in large part because they believed that there were greater political and economic benefits to becoming an American state than remaining a European colony.

As soon as the Louisiana Purchase was completed in 1804, federal officials, Territory of Orleans officials, and local residents struggled to establish institutions that would ensure democratic self-government. Congress eventually approved Louisiana’s statehood in 1812, and President James Madison signed it into law. After statehood Louisiana’s borders underwent minor revisions until the Transcontinental Treaty finally established the boundary separating western Louisiana from eastern Texas.

The Louisiana Purchase created confusing political circumstances in the Territory of Orleans. White men residing in Louisiana received immediate citizenship, allowing them to enjoy the same rights as all other US citizens. But many Anglo-Americans outside the territory claimed Louisianans didn’t know how to be American.

Louisiana’s statehood struggle often involved tense ethnic relations. Most Creoles born in Louisiana, as well as migrants from Canada, the French Caribbean, and France, spoke French, were largely Catholic, and believed themselves to be products of French culture. Other groups of people, including those of Spanish descent and Anglo-Americans, came to Louisiana during the period of Spanish rule. These circumstances led to complex and sometimes-bewildering ethnic relations in Louisiana. Francophone (French-speaking) and Anglophone (English-speaking) people were often at odds. As a result, Louisiana was unlike any other state in the union. French remained a common language in daily conversation and official documents, and Louisiana’s legal system was a blend of Anglo-American common law and French, Spanish, and Roman civil law.

How did enslaved people, free people of color, and Native Americans respond to new restrictions placed on them during the territorial period?

In Louisiana, most white residents, regardless of cultural or political differences, shared a belief in white superiority and a fear of non-white revolt. This outlook was true throughout the United States, but the fear of racial revolt was particularly acute among white Louisiana residents. Not only did Louisiana contain a large population of enslaved Black people, but it was also home to one of the largest and most prosperous communities of free people of color in the United States. Following the Louisiana Purchase, white people in Louisiana restricted the legal rights of free people of color, made it more difficult for enslaved Black people to secure their own freedom, and granted new legal rights to slaveholders.

These new restrictions contributed to the 1811 German Coast Uprising. In 1811 more than eighty enslaved people owned by Manuel Andry in St. Charles and St. John the Baptist Parishes launched an unsuccessful revolt along the German Coast that was the largest uprising by enslaved people in American history. Meanwhile, free people of color used new and existing networks, both among themselves and with white Louisianans, to establish and preserve their own opportunities.

Free people of color proved more successful. Located primarily in New Orleans, they sustained themselves as the largest, most prosperous free Black community anywhere in North America.

Meanwhile, white Louisianans supported federal government efforts to undermine Native American sovereignty and, eventually, force most Native Americans out of Louisiana. Native Americans developed numerous strategies of resistance. The most effective practice was to exploit the boundary tensions that made American officials so anxious. Some Native communities established themselves as allies on the borderlands. Others recognized that the United States and Spain both claiming the same land created a stalemate that could enable Native Americans to remain both neutral and independent. More than any other factor, it was the resolution of boundary disputes between the United States and Spain that tipped the scales against Native Americans. With new boundaries in place, it became increasingly difficult for Native communities to stop non-Native settlement on their lands.