Louisiana Tigers During the Civil War

During the Civil War, Louisiana’s battalions and regiments of foot soldiers were collectively known as the Louisiana Tigers with a reputation for reckless, often alcohol-fueled behavior.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

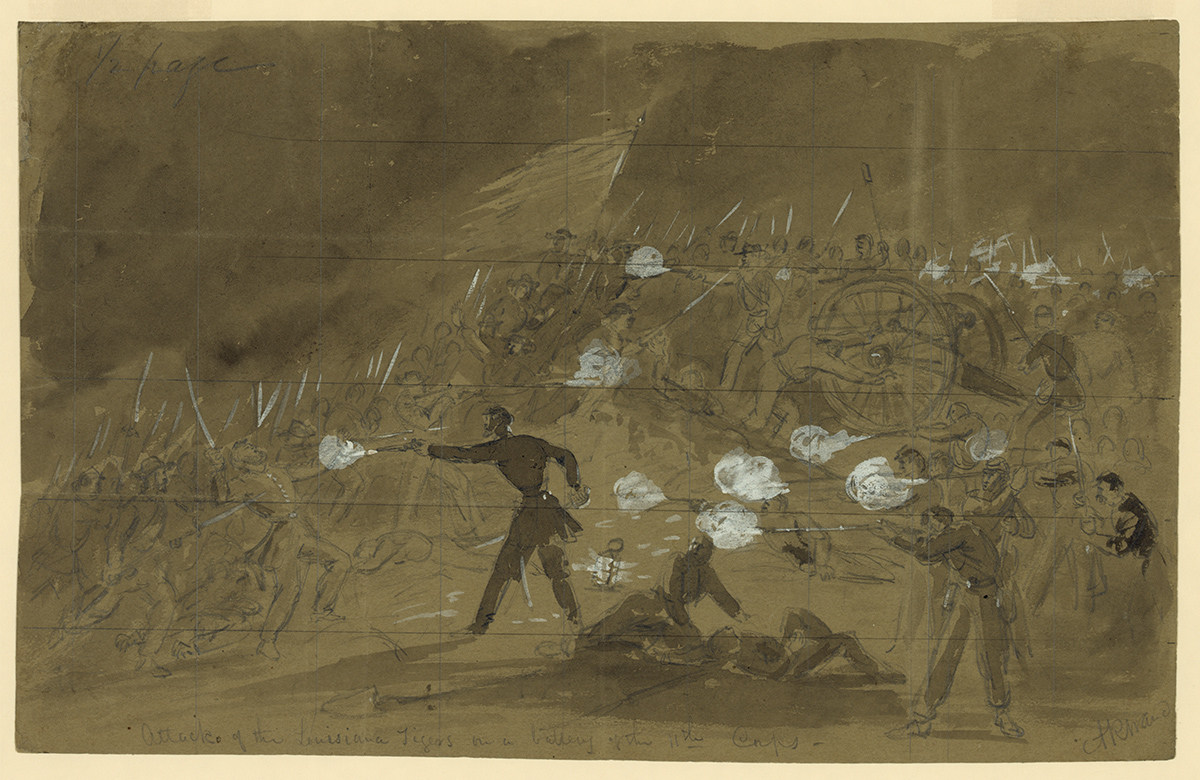

A sketch depicting the "Attack of the Louisiana Tigers on a Battery of the 11th Corps," July 2, 1863. Alfred R. Waud, artist.

Present throughout the Civil War, from First Manassas to Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Louisiana’s Confederate infantry forces were a part of the Army of Northern Virginia and were commonly known as the Louisiana Tigers. The nickname originated with one New Orleans volunteer unit and, due to a combination of fierce fighting and notorious actions, came to encompass a six-company Louisiana battalion. Ultimately, the entirety of the state’s foot soldiers in the Civil War’s eastern theater came to be known as the Louisiana Tigers.

With the onset of the war in April 1861, thousands of white Louisiana men joined hastily assembled infantry companies across the state, prepared to fight for the newly formed Confederate States of America. These locally organized groups of roughly one hundred men each—in units bearing such names as the Carondelet Invincibles, Atchafalaya Guards, and Pelican Greys—mustered into service as the battalions and regiments of foot soldiers that, by the end of the war, were collectively known as the Louisiana Tigers.

Civil War-era Louisiana saw the formation of several units associated with the predatory big cat, groups such as the Calcasieu Tigers and the Rapides Tigers. Yet a New Orleans-based company has the most direct lineage to the Louisiana Tiger brigade: the Tiger Rifles. Raised by Kentuckian Alexander White, the company included dozens of dockworkers and deckhands, many hailing from Ireland and White’s home state upriver, as well as several reported felons. Only two native Louisianans—identified in census records as “mulatto”—appeared on the company rolls. Members embellished their hats with slogans such as “Tiger Found for Happy Land,” “Lincoln’s Life or a Tiger’s Death,” and “Tiger in Search of a Black Republican,” according to local newspapers.

By the spring of 1861 White’s Tiger Rifles, now wearing French Zouave-style uniforms, assembled at Camp Walker on the grounds of the Metairie Racecourse. There they mustered with four other New Orleans companies: Old Dominion Guards, Walker Guards, Delta Rangers, and Rough and Ready Rangers (later Orleans Claiborne Guards). Commanded by Chatham Roberdeau “Rob” Wheat, a Virginia-born veteran of the Mexican-American War and filibuster affair in Nicaragua, the regiment subsequently trained at Camp Moore in St. Helena Parish. With the addition of the Catahoula Guerillas, an array of farmers and merchants from North Louisiana, the men formally organized as the First Louisiana Special Battalion, more commonly known as Wheat’s Battalion.

The five-hundred-strong unit quickly earned a reputation for its reckless, often alcohol-fueled activities, repeatedly brawling with the other volunteer companies at Camp Moore. The First Special Battalion was far from unique, however, as recruits from across the state achieved notoriety in the lead-up to battle and early days of the war. The Fourteenth Louisiana (including Carroll Parish’s Tiger Bayou Rifles) and Georges de Coppens’s Louisiana Zouaves proved particularly troubling as, according to local accounts, they fought, drank, and looted across the countryside en route to Virginia.

Such aggressive, often violent tendencies served the foot soldiers well on the battlefield, gaining the Louisianans early praise in the war’s eastern theater. During the First Battle of Bull Run, Wheat’s Battalion—including White’s Zouave-uniformed Tiger Rifles—played a key role in repelling Union forces, even after the major took a bullet to the chest. For their conduct in the conflict’s opening battle, Wheat’s entire unit became colloquially known as the Tiger Battalion.

The animal moniker gained wider use as disquieting stories of the First Louisiana Brigade’s exploits circulated through the Confederate ranks. Their infamy exploded in the wake of the Union’s Peninsula campaign in southeast Virginia, with the press repeatedly reporting on their drunken brawls, livestock killings, and indiscriminate thievery. Barely a year into their deployment, their reputation and nickname had become firmly established: the scrappy infantry brigade would simply be known as the Louisiana Tigers.

Despite their loutish misdeeds the Tigers also achieved acclaim for their efforts on the battlefields of Virginia. Stonewall Jackson’s campaign through the Shenandoah Valley saw them join with the First Maryland Infantry to force a Union retreat at Front Royal on May 23, 1862. At the Second Battle of Bull Run three months later, the Tigers of the newly created Second Louisiana Brigade repelled federal forces using only rocks and stones after exhausting their ammunitions supply. However, the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 and the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864 resulted in heavy losses for both brigades, ultimately leading to their consolidation in the spring of 1864.

By the time of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox the following year, nearly thirteen thousand men had served in the state’s eastern theater infantry collectively known as the Louisiana Tigers. A quarter of these foot soldiers did not live to see the end of the war and the Confederacy’s dissolution. Fueled in part by romanticized narratives of the Lost Cause, the soldiers’ renown only grew in the decades that followed, and in 1896 Louisiana State University adopted the name Louisiana Tigers for its football team.