Manumission

Manumission is the formal act or process of being released from slavery.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

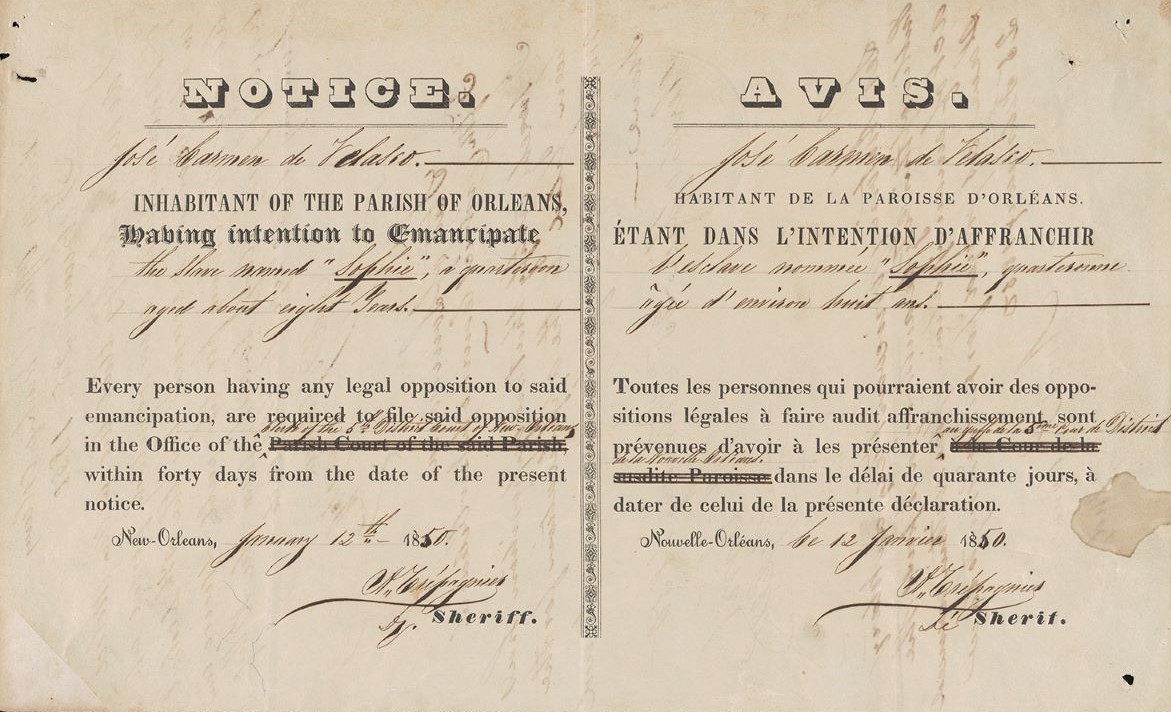

Orleans Parish Sheriff's notice of José Carmen de Velasco's intent to manumit an eight-year-old girl named Sophie.

Manumission is the formal act or process of being released from slavery. On the eve of the Civil War, Louisiana was home to the largest population of free people of African descent in the Deep South despite enslaved Africans and African-descended people making up almost half its population. This free Black population originated primarily from manumissions during the French, and especially the Spanish, colonial periods. Around the same time as the Louisiana Purchase, an influx of free people of color, who were refugees of the Haitian Revolution, enlarged the free Black population. As Louisiana’s plantation economy expanded, moving deeper into the nineteenth century, the state government placed increasing restrictions on manumissions.

Manumission in French Colonial Louisiana

After the founding of New Orleans in 1718, French colonial authorities imported thousands of enslaved Africans to establish a slavery-fueled plantation economy centered on tobacco production. Between 1719 and 1743 slave traders brought around six thousand enslaved Africans, mostly from the Senegambia region, as well as many others from the Caribbean, to the Louisiana colony. In 1724 the French Crown the Louisiana Code Noir, which was intended to bolster slavery and provide guidance for enslavers in managing the enslaved.

The Code also regulated the process of manumission. It prohibited enslavers under the age of twenty from freeing enslaved people and required a “decree of permission” from the Superior Council, the colony’s judicial body, for any manumission. Some men who had fathered children with enslaved women freed the mother or, more often, their mixed-race children. However, the most common reason for manumission was as a reward for military service on behalf of the French against their Native American enemies. Several dozen enslaved Africans who fought for the French against the Natchez Indians in the 1720s were rewarded with freedom. In 1736 more than one hundred enslaved Africans were granted freedom for enlisting to fight Chickasaws on behalf of the colony. The arming of enslaved Africans to fight on behalf of the colony during the French period formed the basis for an institutionalized free Black militia during the Spanish period.

Manumission in Spanish Colonial Louisiana

Louisiana became a Spanish colony in 1762, though Spain did not take official control of the colony until 1768. During the Spanish period manumissions increased significantly, and the free Black population in Louisiana grew, from just over three thousand in 1771 to more than eight thousand at the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Spanish law in Louisiana was more favorable to manumission than the Code Noir. While the Code limited the ability of enslavers to manumit the enslaved, the Spanish custom of coartación, imported from Cuba, gave enslaved people the right to purchase their own freedom—even without the enslaver’s approval—for an agreed-upon price or a price set through arbitration. Moreover, French law forbade enslaved people from owning property, while Spanish law did not. Thus enslaved people could legally build up the means of self-purchase. Coartación led to a rise in manumissions during the Spanish period. In more than three decades of Spanish rule, over nineteen hundred enslaved people were freed, with manumissions increasing significantly with each decade. Between a quarter and a third of these manumissions continued to be white male enslavers freeing their mixed-race children and, less frequently, the mothers of these children. However, established and propertied free Black people increasingly purchased the freedom of enslaved relatives and intimate partners.

Under Spanish rule military service remained an avenue to freedom and became a source of collective identity for free men of African descent. Spanish law and custom provided that enslaved people should be freed for valiant military service, with the government compensating the enslaver for property loss.

Manumission in American Louisiana

The United States acquired Louisiana in 1803, after Napoleon’s failed attempt to reestablish slavery in the French colony of Saint-Domingue and just as plantation slavery was expanding in the Lower Mississippi Valley. The Haitian Revolution produced tens of thousands of refugees, many of whom ended up in Louisiana. Within a decade of the Louisiana Purchase, ten thousand refugees were living in New Orleans and its environs. While slavery had been abolished in the French Caribbean during the French and Haitian Revolutions, the liberty of the formerly enslaved was not recognized in the United States. In Louisiana the refugees were categorized as white, enslaved, or free people of color, with about a third falling into the last category. About three-quarters of the adult refugees of color were women. However, their freedom was precarious because many did not have sufficient documentary proof of their free status to satisfy Louisiana authorities, and this made them vulnerable to illegal enslavement and sale in the slave market. Dozens of kidnapped or otherwise illegally enslaved people of African descent resorted to the Louisiana court system to preserve or regain their freedom.

Louisiana’s laws and social conditions under the United States during the nineteenth century were less conducive to manumission than in earlier periods, and manumission restrictions increased as the Civil War approached. As slavery rapidly expanded throughout the Deep South, state governments in the region took steps to reduce the free Black population, and Louisiana was no exception. An 1807 law required approval by the territorial and then state legislature for the manumission of an enslaved person under age thirty. Beginning around 1830, in response to fears of rebellions of enslaved people and the rising abolitionist movement, state legislatures throughout the South sought to decrease the size of free populations of African descent. In 1830 the Louisiana state legislature required anyone who freed an enslaved person to post a thousand-dollar bond to guarantee that the freed person would leave the state within thirty days. An 1852 law required any manumitted person to leave the United States entirely. In 1857 the legislature outlawed manumission altogether. Louisiana’s free Black population declined in the late antebellum period, from over twenty-five thousand in 1840 to less than nineteen thousand in 1860, a result of free people of color leaving the state or identifying as white.

Conclusion

Manumission in Louisiana was shaped by international events; the different policies of France, Spain, and the United States; and changing socioeconomic conditions. Under the French a free Black population emerged from manumissions primarily as a reward for military service on behalf of the colony. Under Spanish rule manumissions accelerated dramatically. Even as a plantation economy grew in the late Spanish period, coartación ensured that manumissions continued unabated. Ironically the Louisiana Purchase led to both a massive increase in the free Black population and greater restrictions on manumissions. As plantation slavery expanded and a racial defense of slavery solidified in the face of increasing abolitionist attacks, the very existence of a large population of free people of African descent was seen as a threat to the social order, and manumissions were eventually banned altogether. By February 1861 Louisiana had seceded from the Union to protect slavery. The war that followed would eventually lead to the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment—manumitting all the enslaved people in the United States.