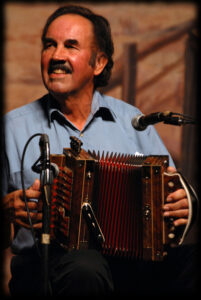

Marc Savoy

Marc Savoy is a Cajun folklorist, musician, and master accordion maker in Eunice.

Courtesy of Cajun and Zydeco Photos, David Simpson

Marc Savoy. Simpson, David

Musician Marc Savoy builds and repairs Cajun accordions in his Eunice shop, the Savoy Music Center. The store, which opened in 1966, serves as a gathering place for local Cajun musicians and fans from around the world; a jam session takes places there on most Saturday mornings. Savoy, an advocate for the preservation of Cajun music and culture, has played with Dennis McGee, D. L. Menard, and Michael Doucet, among others. He also performs with his wife, Ann, and sons, Joel and Wilson, as the Savoy Family Band. In 1982, the National Endowment for the Arts honored his contribution to tradition music with a National Heritage Fellowship. He also appeared in PBS documentary series American Roots.

Marc Savoy was born October 1, 1940, the son of Joel Savoy and Mabel Billideaux. He grew up an isolated rice farm near Eunice, in the rich cultural milieu forged by French-speaking Acadian (from which the term Cajun is derived) refugees from eastern Canada; they immigrated to southwestern Louisiana in the late eighteenth century. The first time music made an impression on him was when he was seven years old and visiting his grandfather. He recalls, “After a while, my father [Joel Savoy] asked my grandfather, ‘Pop, get out your fiddle and play us a tune.’ My grandfather slowly got up, went into one of the back rooms, and returned with a small oblong black case which he proceeded to open with the most gentle affection. From the little black case, he removed a very odd-looking wooden object and began turning little pegs while plucking the strings. At this young age … I think the thing that impressed me as much as the sounds being emitted from the little wooden box was the look that came over my grandfather’s face … it was as though he was no longer in the room with us. From that moment on, I remember thinking ‘When I grow up, I want to be able to make sounds like that.’”

From that day on, Savoy spent nearly every afternoon with the French-speaking older men who gathered at his grandparents’ home playing music and reminiscing. For him, those older folks represented “a way of life that was like a big, soft, warm blanket on a winter night.” Growing up, he fell in love with the button accordion but couldn’t find anyone to teach him to play it or to make one. When he was twelve years old, he made one himself from household items, such as his grandmother’s tablecloth that he used to line the cardboard bellows, and toilet float rods to make the levers that attached to the keys.

Later, his father bought him a new instrument from the Sears Roebuck catalogue for $27.50. By the time the accordion arrived, Savoy said, he felt that he was already able to play. “With all the music that I had soaked into me before my new accordion arrived, it was only natural that some had leaked out through my fingers on the buttons…. There were certain things I wanted to do, but my instrument couldn’t keep up with.” When Savoy was not playing his Hohner accordion, he was disassembling and reassembling it to see how it worked.

One day, his family attended a party at his father’s cousin’s home. Cyprien Landreneau and his cousin, Alton Landreneau, an extraordinary accordionist, were providing the music for the party. “The moment we arrived,” Savoy says, “I jumped out of the car and, hearing the sound of the accordion, I told my family ‘Wow! Listen to the sound of that accordion!’ My father said ‘What do you mean? It’s just an accordion.’ I replied ‘Oh, no, it is not.’” Savoy eventually learned that this accordion was a pre-World War II Monarch instrument from Germany. Later, he was able to purchase a dilapidated Monarch accordion, which he restored to mint condition. Word of his restoration skills spread, and soon he was repairing other people’s instruments. Gradually, Savoy developed very specific ideas of what an ideal accordion’s timbre, tone, and performance capacities should be.

While developing his ideal accordion, Savoy continued his formal education and earned a B.S. in chemical engineering. After graduation, he interviewed with a major chemical company in the Northeast and decided two things: He did not want to leave Louisiana, and he wanted to pursue his interest in accordions more than he wanted to be a chemical engineer. In 1965, he opened a music store and went full-time into the business of building accordions. Over the next decade, Savoy’s Acadian instruments became widely recognized and were in demand by musicians who appreciated their superior tonal quality.

Savoy’s accordions were used primarily, but not exclusively, by Cajun musicians. When Savoy heard French Canadian accordionist Philippe Bruneau play, he realized how limited his knowledge of accordion music actually was. Having been raised within the Cajun music tradition, Savoy didn’t fully understand how varied the different accordion musical styles were. He was inspired by Bruneau’s musical genius and applied that inspiration to building an accordion for the musician. In addition to stimulating his interest in more diverse accordion musical performance styles, Savoy’s exposure to Bruneau increased his awareness of how Cajun music had been influenced by the country and western style.

In 1977 Savoy married Ann Allen, a native of Virginia, and over the years they have performed together in the United States and abroad. Ann Savoy has written extensively on the history of Cajun music, and has worked and performed with her husband to preserve traditional Cajun culture.