Ozeme Carriere

Ozeme Carriere led one thousand guerilla fighters, including enslaved people and free people of color, in resisting the Confederate draft.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

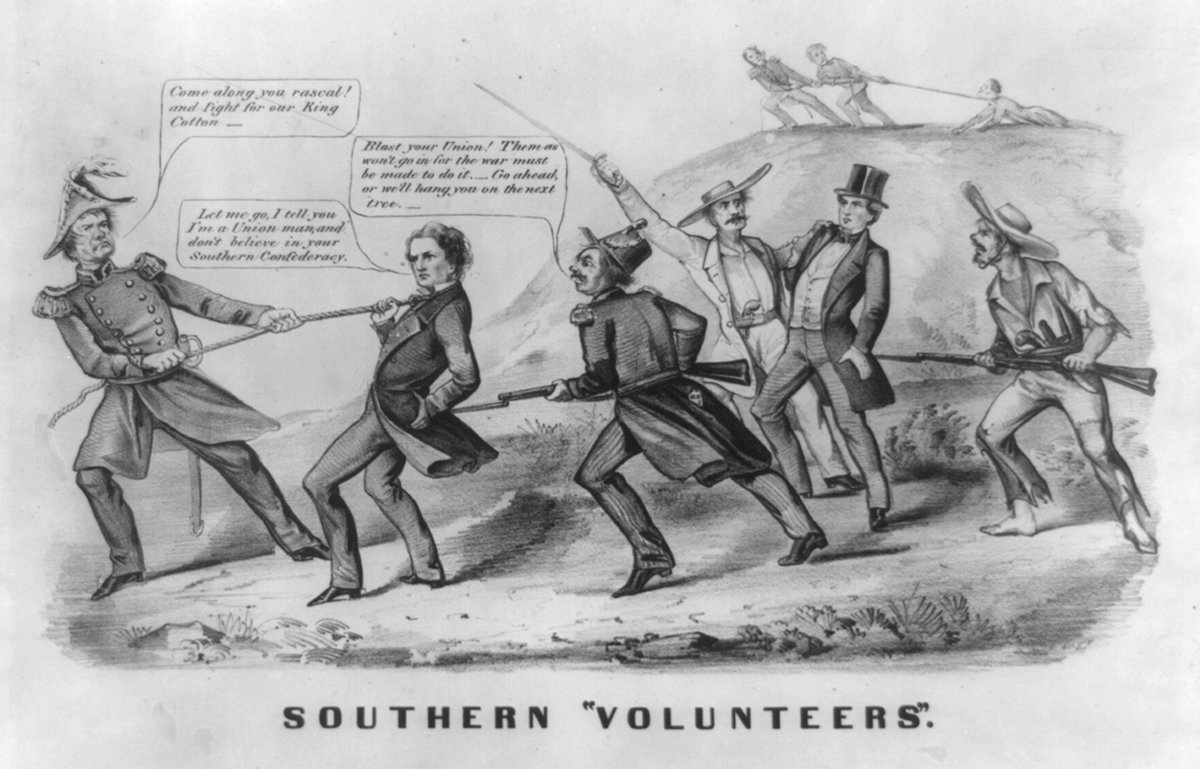

Political cartoon depicting Confederate troops using force to recruit men to join the Confederacy against their will, c. 1860s.

Ozeme Carriere was a resistor to the Confederate draft during the American Civil War. From the spring of 1863 until his death at the hands of Confederate cavalry in May 1865, Carriere led guerilla fighters in St. Landry Parish west of Opelousas. Members of the Confederate government and the pro-Confederate press labeled him and his followers Jayhawkers, in reference to antislavery guerilla fighters in Kansas during the 1850s. Though they were anti-Confederates, Carriere and his followers were not necessarily abolitionists or even strong supporters of the Union.

Much of Carriere’s early life is unknown. He was the youngest of seven children, born in St. Landry Parish in 1831, a few months after the death of his father. In 1860 a census recorder found Carriere living on a small farm with two free women of mixed racial ancestry; both were named Mary Guillory, and one was old enough to be the mother or aunt of the other. Like his neighbors, Carriere was illiterate and poor. The elder Mary Guillory, potentially his partner, was not the only free person of color around. Carriere, like many poor white people in the South, lived on the margins of the slave-based plantation economy and in close proximity to poor free people of color and enslaved people. When Louisiana seceded from the United States in 1861 to protect slavery, people like Carriere had little reason to fight for their state in the ensuing war, seeing no personal benefit. Some resented the wealthy plantation owners who often dominated politics in southern states. Others, of course, joined the fight because they felt that threats to slavery were also threats to white supremacy, which was sometimes the only thing that gave poor white people status, rights, and power over Black people. Carriere’s views are a mystery.

When the Confederacy passed a conscription act in 1862, Carriere and his peers had reason to resist. After Union forces routed the Confederates in the Bayou Teche region in the spring of 1863, many recusant conscripts and conscript-aged men deserted for the woods and swamps of southwestern Louisiana. Carriere came to lead a band in the Bois Mallet area, west of Opelousas near present-day Eunice.

As the war dragged on, Carriere attracted more supporters, including enslaved people and free people of color. Martin Guillory, brother of Carriere’s possible partner Mary, became one of his lieutenants. By February 1864, Carriere counted around one thousand men under his command. They resisted attempts by Confederate soldiers and militia to force them into military service. They also raided nearby farms and towns to hamper the Confederate war effort and to supply themselves with food and other necessities. By May 1864, Confederate General Richard B. Taylor ordered the 4th Louisiana Cavalry to kill or capture the guerillas. The war between the Confederates and Carriere’s band lasted a year.

The twilight of the Civil War proved to be Carriere’s downfall. The threat of the Confederate draft waned and then collapsed after crushing Union military victories in the winter and spring of 1865. Most of Carriere’s guerillas returned to their homes, leaving Carriere vulnerable to attack. Brought to their knees but not yet defeated, the Confederate military and the secessionist Louisiana government continued to pursue Carriere. The cavalry caught Carriere and killed him in May 1865.

Carriere was not the only resistor to the Confederate draft during the Civil War (the most famous being Newton Knight, the subject of the 2016 film Free State of Jones). His resistance to the Confederacy and the common cause he found with Black people underscore the complexity of the US South and Louisiana during the Civil War era.