Shape Note Singing

Shape-note singing dates from the late seventeenth century and is a system of printed shapes, instead of standard music notation, to help untrained singers learn how to read the music.

Public Domain.

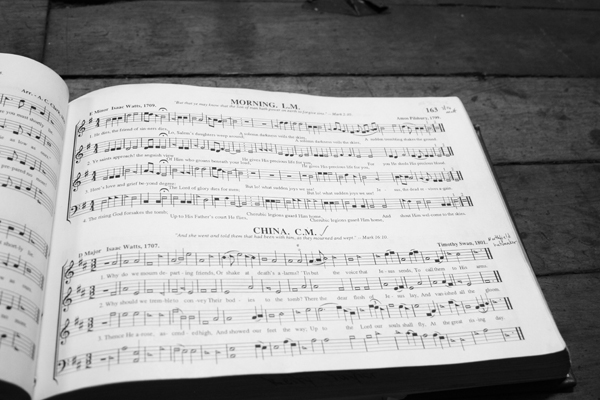

A black and white image of shape note music.

Shape-note singing is a form of a capella music, predominately of Christian hymns, that is typically sung in four-part harmony. These parts are primarily sung by groups of varying size, rather than by quartets with only one singer per part. The term shape-note refers to a simplified form of conventional musical notation that is intended to be easier to learn than the standardized form. This system normally uses four distinct shapes—a triangle, circle, square, and diamond—to correspond to the syllables fa, sol, la, and ti. Some groups use a more complex seven-shape system that still differs from conventional notation.

The first widely accepted system of shape-notes appeared in The Easy Instructor by William Little and William Smith, published in 1801 (and possibly earlier), although the Boston minister and music teacher Andrew Law introduced a similar system with “lozenge notes” in 1803 with The Musical Primer.

Shape-note singing first arose in colonial New England, where it was taught by itinerant singing masters who worked a circuit of small towns, setting up shop for a week or two and then moving on. The range of these roving instructors widened in tandem with westward and southward expansion and was associated with the Second Great Awakening, a resurgence of Protestantism that swept New England, the mid-Atlantic, and the South between 1790 and the 1840s. Eventually shape-note singing faded in the East, but it has survived in the South. In some quarters, especially among well-educated devotees of classical music, emergent shape-note singing was scorned as low-class music for the semiliterate masses.

Other observers of the era were more tolerant, however: “Yet the simple strains of those days were as perfectly adapted to those who made them as Wagner, Lizst, Mendelssohn, and Chopin are to us today.”

Shape-note singing material overlaps with other traditions, including gospel music. Some of the shape-note repertoire (although not the notation itself) appeared in various eighteenth-century songbooks, many of which echoed such bedrock British works as Isaac Watts’s Hymns and Spiritual Songs, published in 1707. One of the first important shape-note hymnals was The Southern Harmony; in an 1845 edition, its full title was The Southern Harmony and Musical Companion: Containing a Choice Collection of Tunes, Hymns, Psalms, Odes, and Anthems: Selected from the Most Prominent Authors in the United States: Together with Nearly One Hundred New Tunes, Which Have Never Before Been Published. Another popular work, The Original Sacred Harp, appeared during the nineteenth century in numerous versions and remains in print today. That “sacred harp” has become an alternate name for shape-note singing illustrates the extent of this book’s influence.

In Louisiana, shape-note singing is more apt to be heard in the northern parishes alongside other aspects of rural Anglo culture. Some African-Americans also practice the tradition, particularly in the state’s northeast Delta region. The practice occurs both at church services and at gatherings known as “singings.” In addition, echoes of the shape-note aesthetic are present in the music of north Louisiana close-harmony singers like the Whitstein Brothers, from Pineville, and from mid-century Louisiana Hayride performers like the Bailes Brothers. It also influenced gospel-tinged musicians like rockabilly pioneer Jerry Lee Lewis, whose music and career reflect a deep tension between sacred and secular material. Despite the stronger associations with north Louisiana, at this writing, Louisiana’s only chapter of the Sacred Harp Musical Heritage Association is in Mandeville, Saint Tammany Parish.