Sherwood Anderson

Sherwood Anderson first arrived in New Orleans in 1922 and quickly became the charismatic center of the arts scene now known as the French Quarter Renaissance.

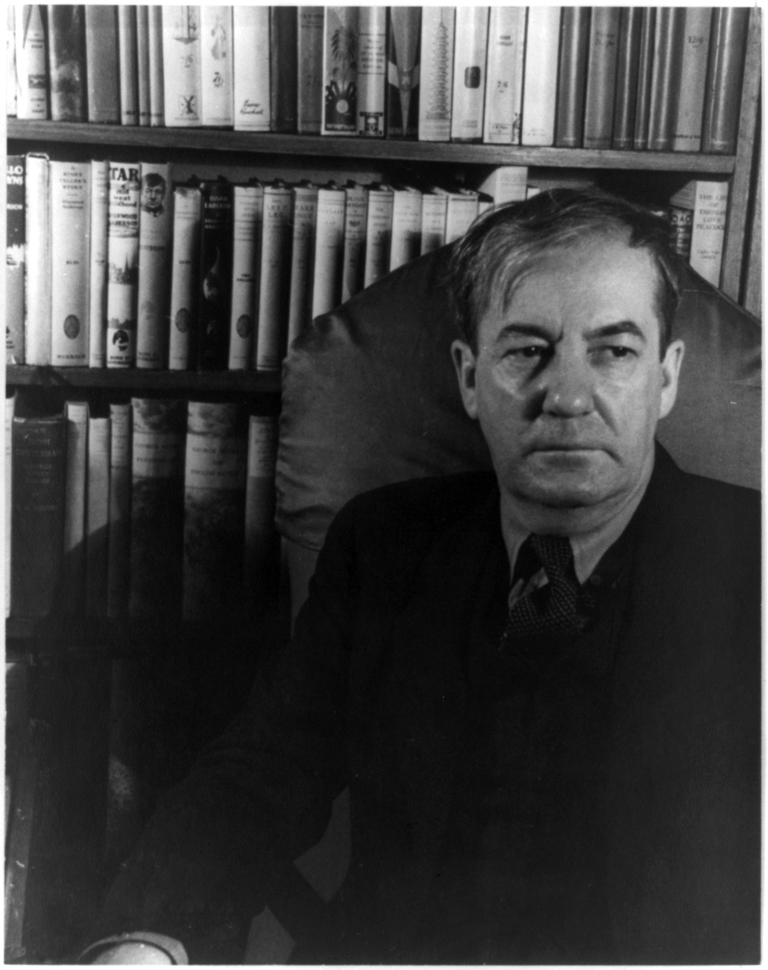

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Portrait of Sherwood Anderson. Carl Van Vechten (Photographer)

An American writer known for his pioneering literary work of the early twentieth century, Sherwood Anderson earned international literary fame and mentored such emerging writers as William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. Eccentric in his passions and prone to fits of despondency, Anderson traveled extensively, divorced frequently, entertained almost nightly, and wrote prolifically throughout a star-studded career that spanned nearly three decades from his first novel in 1916 until his death in 1941. His most enduring work—a collection of short stories entitled Winesburg, Ohio, published in 1919—helped launch a remarkable century of definitively American literature and inspired a generation of writers that included John Steinbeck and Thomas Wolfe.

Early Years

Anderson was born on September 13, 1876, in Camden, Ohio, and moved often throughout his early years as his father’s fortunes sank lower and lower. By the time he was fourteen, Anderson had left school to work odd jobs, and at eighteen he joined the National Guard. In 1899 he was deployed to Cuba during the Spanish-American War. After his military service, Anderson returned to Cleveland, Ohio, where he became a successful advertising salesman and writer. His busy work schedule was rivaled only by his exuberant social life. He and his wife, Cornelia Pratt Lane, entertained frequently and attended all manner of events. Despite the happy exterior, however, Anderson was feeling a great deal of stress and suffered the first in a series of nervous breakdowns that would ultimately change his life forever.

When his own fortunes began to falter, Anderson found himself in Elyria, Ohio, selling industrial paint. The business thrived, but Anderson did not. Another mental breakdown sent him wandering on foot some thirty miles back to Cleveland, where days later he was discovered lost and wandering through a drugstore. Soon after that, Anderson decided to make a major life change: he abandoned his wife and children, moved back to Chicago, and began writing literature. Along the way, he divorced Lane and remarried to the sculptor Tennessee Claflin Mitchell.

The Writing Life

In Chicago, Anderson fell in with such writers as Theodore Dreiser and Carl Sandberg, and he made his first serious attempts at literary fiction. He landed a three-book deal with the publisher John Lane who issued Anderson’s first two novels, Windy McPhereson’s Son (1916) and Marching Men (1917). It was Anderson’s third book, however, that catapulted him to success. With Winesburg, Ohio, Anderson found his voice, telling the realistic, beautiful, and often grim tales of turn-of-the-century middle America. With his direct approach to narrative, everyman characters, and no-frills literary style, he captured the modern zeitgeist that was propelling a new generation of American writers. A follow-up collection, the Triumph of the Egg (1921), did quite well, and by the time he won the first annual Dial magazine award for fiction, Anderson’s fame was spreading on both sides of the Atlantic. His personal life, on the other hand, was in tatters.

The New Orleans Years

Anderson first arrived in New Orleans in 1922. He was flush with his prize money and separated from his latest wife, and this time would prove to be one of the happiest stretches of his life, as he was freed from financial and personal concerns to pursue the craft and art he so admired. As biographer Irving Howe noted, “Seldom before and probably never afterwards did Anderson feel so radiant and vigorous, so ready to forget for the moment the personal and career troubles of Chicago and New York. When the Mardi Gras was held he threw himself into it was a rich zest.”

It helped that New Orleans was in the midst of an artistic renaissance of its own, with an eclectic and talented assortment of artists and writers converging on the old French Quarter to create something of a modern bohemia. Many of these characters swirled around a local publication called the Double Dealer, which Anderson visited right away. Julius Friend, the magazine editor, later recalled his first meeting with Anderson: “He was an exotic spectacle! His long hair fell in strands over his florid face. His apparel: a rough tweed suit with leather buttons, a loud tie on which was strung a large paste finger ring, red socks with yellow bands, a velour hat with a red feather stuck in it. He carried a heavy blackthorn stick.”

For his part, Anderson found the gang who gathered around the Double Dealer to be “as pleasant a crowd of young blades as ever drank bad whiskey.” He went on to enjoy his time in New Orleans so much, in fact, that within two years he had permanently relocated to a French Quarter address, along with a new wife, Elizabeth Norman Prall. Anderson fashioned himself into something of a Falstaff, the charismatic center of a thriving arts scene, and even the newspapers began to refer to him as the “Lion of the Latin Quarter.” One of the artists who drifted into this scene was a young writer named William Faulkner. Anderson was generous with his time and advice, and he enjoyed being surrounded by young, eager writers and artists. He befriended the young Faulkner and helped him publish his first novel, Flags in the Dust (1927).

Later Career

Eventually, the heat got to him. Anderson would write in a letter, “We have tropical rains almost daily. You sit working and the water runs off your back.” He moved to the hill country of Virginia, where he built a large home called Ripshin. It was more than his stamina that was beginning to fade, however. Despite writing his only bestseller, Dark Laughter (1925), while in New Orleans, the critics had begun to turn on him. He had lost something of his old voice and edge. One of the most vicious critics was another young writer named Ernest Hemingway, a man who had once been Anderson’s protégé but who now saw an opportunity to knock off a competitor. Hemingway wrote a parody called Torrents of Spring (1926) that was ruthless in its attack on Anderson’s style and persona. Years later, Anderson wrote in a memoir, “It was so raw, so pretentious, so patronizing, that it was amusing but I was filled with wonder … I thought it foolish that, while there was so much to be done in writing, we writers should devote our time to the attempt to kill each other off.”

As he had done many times over the course of his life and career, Anderson reinvented himself once more. He divorced and remarried, this time to a much younger woman named Eleanor Gladys Copenhaver who was active in the labor movement. He continued to write—fiction and news articles—toured on the lecture circuit, and became involved in politics. Finally, he planned a goodwill tour to South America. Before he left, however, he embarked on a series of bon voyage parties across New York City, and somewhere along the way he accidentally swallowed the toothpick from a martini or hors d’oeuvre. Unbeknownst to him, that toothpick would perforate his intestine and cause a deadly infection. He made it as far as Panama before disembarking with his wife and being rushed to the hospital. He died on March 8, 1941, at the age of sixty-four in Colon, and his body was returned to the United States and buried in Marion, Virginia, near his beloved Ripshin.