The Double Dealer

A New Orleans-based literary journal, The Double Dealer was published over a period of five and a half years, between January 1921 and May 1926.

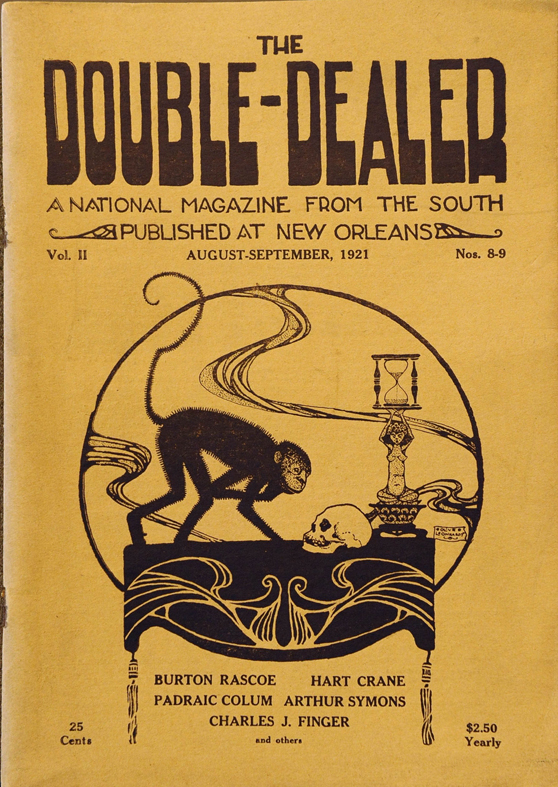

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

The Double Dealer, 1921 cover. Leonhardt, Olive (Artist)

A New Orleans-based literary journal, The Double Dealer was published over a period of five and a half years, between January 1921 and May 1926. The founders of the journal, a group of journalists and poets, hoped to establish a claim to literary legitimacy for the South in general and New Orleans in particular. The magazine featured works by scions of literary modernism such as William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate, Djuna Barnes, Hart Crane, and many others. For a time, it was the preeminent literary magazine in the South. Even after it ceased publication, The Double Dealer left a powerful intellectual legacy for southern letters.

Predecessors and Goals

As Thomas Bonner Jr. has pointed out, The Double Dealer came out of what is known as the little-magazine tradition, which had its initial roots in New Orleans in De Bow’s Commercial and Financial Review. De Bow’s was a publication of the mid- to late nineteenth century which, despite its name, had a pronounced literary focus. As The Double Dealer would after it, De Bow’s sought to celebrate and publicize the intellectual life of the South in the face of critics’ assertions that the region was provincial and backward. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a number of local artistic and literary journals, many published by women, provided regional writers with an outlet for publication and legitimacy. Anchored in this tradition, The Double Dealer was informed and inspired by a changing South and the transformative currents of modernism.

The Double Dealer’s title was drawn from William Congreve’s play of the same name, which, the founders believed, dealt with “the raw stuff” of human nature—something they, too, intended to do. In the first issue, founding editors Basil Thompson, a poet, and Julius Friend, a cultural critic, proclaimed that the journal’s goals were to “appeal once more…to that select audience for whom romance and irony lie not so many leagues apart; whose veneration for art, music, and letters, is not so solemn that it cannot be lightened by a sense of humor; whose opinions of society, economics, and politics are drawn, not from the perusal of dusty books, but rather from the vision of tolerant eyes estimating the devious ways of the world.”

Beyond this characterization of its intended audience, the goals of The Double Dealer were ambitious and complex. Its editors subtitled it “A National Magazine for the South,” positioning it as a rebuttal to criticisms—most notably H. L. Mencken’s scathing 1917 essay “The Sahara of the Bozart”—that the South was lacking in artistic and intellectual culture. The Double Dealer’s tone and presentation were defiantly grandiose. The journal was full of classical imagery, underscoring its claim to literary and cultural legitimacy. Yet, for all its evocations of tradition, both classical and southern, The Double Dealer also reflected the powerful currents of modernism that were transforming literature and art in the 1920s.

In some ways, the publication is best defined by the tensions it navigated. It walked a line between a regionalist focus, on one hand, and the energy and force of nascent modernism, with its experimental, internationalist spirit, on the other. The tension between past and present was matched by other tensions—between local and national, male and female—that gave the magazine much of its energy. Its editorials were ambitious and sometimes outrageous, as in the case of a piece in the third issue entitled “The Ephemeral Sex,” a broadside of debatable sincerity aimed at women artists. Despite this article’s sexist tone, women writers were well represented in The Double Dealer.

Notable Works and Impact

During its short run, The Double Dealer published a number of notable pieces by an array of important literary figures. Sherwood Anderson’s piece, “New Orleans, the Double Dealer, and the Modern Movement in America” connects the magazine’s mission to the broader intellectual currents of American modernism. William Faulkner‘s collection of sketches entitled “New Orleans,” along with a number of poems, essays, and reviews, appeared in The Double Dealer just as he was beginning to develop into a great modernist writer. In addition to Faulkner and Anderson, the Double Dealer published works by a veritable who’s who of American literary modernism; Ernest Hemingway, Amy Lowell, Hamilton Basso, Thornton Wilder, and Allen Tate published in the journal. The Double Dealer also included African American writers, encouraging a recognition and celebration of writers and artists of color. Throughout the journal’s life, it managed to maintain both its regional and national character, becoming a vital part of the national literary scene while retaining a clear and emphatic New Orleans character.

Legacy and Significance

While The Double Dealer’s life span was relatively short, its impact on the literary and cultural life of the South and the nation has been significant. By garnering national acclaim, it bridged the gap between regional and national writing, and served as a catalyst of the Southern Renaissance, an outpouring of literature by southern writers between the two World Wars. It influenced future literary journals like The New Orleanian, which succeeded it in 1930; the Iconograph, which began in 1940; and, perhaps most famously, the Southern Review. The journal’s most direct legacy is its namesake publication, Double Dealer Redux, now published by the Faulkner Society, headquartered in the apartment where Faulkner once lived in New Orleans. As an early outlet for some of the great writers of American modernism, a resounding claim for southern literary legitimacy, and a force moving New Orleans toward prominence as an international literary center, The Double Dealer had cultural impact well beyond its brief publication run.