Shirley Ann Grau

New Orleans born writer Shirley Ann Grau is noted for her depictions of southern landscapes and Louisiana folkways in her fiction.

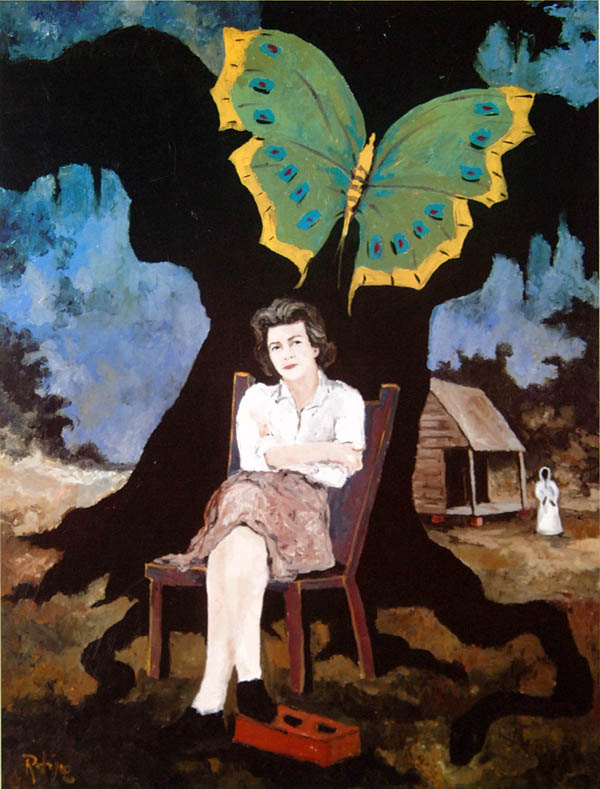

Courtesy of George Rodrigue

"Shirley Ann Grau. Setting the Limits of Her World". Rodrigue, George (Artist)

New Orleans-born writer Shirley Ann Grau is noted for her depictions of southern landscapes and Louisiana folkways in her fiction. Her stories of abortion, miscegenation, destruction, and death recall earlier periods in southern and Louisiana history. Yet she also confronts significant social and cultural topics that reach beyond southern borders, especially as these topics relate to the lives of women. For this reason, Grau remains important in studies of not only southern and Louisiana fiction but also women’s fiction.

Early Life and Career

Born on July 8, 1929, in New Orleans, Shirley Ann Grau—the daughter of Adolph and Katherine Onions Grau—spent her childhood in both New Orleans and Montgomery, Alabama. Grau completed her high school education at the Ursuline Academy in New Orleans before attending Sophie Newcomb College at Tulane University, where she pursued a degree in literature. She published her first short story, “For a Place in the Sun,” in Surf, a university magazine, in April 1948. Between 1949 and 1951, the stories “So Many Worlds,” “The Shadowy Land,” “The Lonely One,” “The Things You Keep,” and “The Fragile Age” appeared in Carnival, another university publication.

Upon graduation, Grau entered Tulane University with the intention of studying for a graduate degree in literature. After discovering that the chair of the English department would not hire females as teaching assistants in the program, Grau chose to continue writing fiction instead of completing her master’s thesis. Before The Black Prince (1955), her first collection of short stories, was published, Grau had placed three of the stories. “Joshua” was first published in The New Yorker, “White Girl, Fine Girl” in New World Writing, and “The Black Prince” in The New Mexico Quarterly. The stories in this collection range from the fantasy of “The Black Prince” to the bayou folk of “Joshua.”

The year 1955 marked not only the publication of The Black Prince but also Grau’s marriage to James K. Feibleman, a Tulane philosophy professor. While establishing her reputation as a writer, Grau lived with her husband and four children in Metairie, a suburb of New Orleans, and Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, dividing the year between the two homes. Her continued connection with the New Orleans area and Louisiana in general greatly influenced her work. She captures the harsh conditions and natural violence of hurricane season on a small Louisiana island in The Hard Blue Sky (1958), her first novel, and the realities of choosing abortion in uptown New Orleans in The House on Coliseum Street (1961). Grau’s oeuvre also includes the novels The Condor Passes (1971), Evidence of Love (1977), and Roadwalkers (1994). These novels continue her narrative exploration of families and use of multiple points of view. Her short story collections include The Wind Shifting West (1973) and Nine Women (1985).

Grau’s Sense of Place

Grau’s detailed descriptions of places, especially in Louisiana, and cultural traditions make her work significant in studies of Louisiana literature. The setting in The Hard Blue Sky is central to its theme of nature’s indifference, a reality experienced by many Louisianians each year during hurricane season. An isolated island, Isle aux Chiens is populated by an ethnically mixed folk community made up of African Americans, Cajuns, Creoles, Spanish, and Native Americans who live a harsh life, enduring natural forces and family conflicts. The novel opens with a geographical description of the island, complete with a catalogue of changes that have occurred as a result of past hurricanes. Alterations to the landscape are paralleled by cultural transformations, including the introduction of the first washing machine and landline phone on the island. Such instruments of progress coexist with folk medicines, traditional tales of the loup-garou (werewolf), and local foodways.

While her first novel records the lives and trials of isolated islanders, The House on Coliseum Street relates the story of twenty-one-year-old Joan Mitchell and her decision to have an abortion. The uptown home where the novel takes place marks a departure from the island home of The Hard Blue Sky, yet similarities exist among these stories and Grau’s other works. Grau continues to use multiple points of view to narrate the story, and the rainstorm that opens The House on Coliseum Street suggests once more nature’s indifference to the human condition.

Grau’s third, and Pulitzer Prize–winning, novel The Keepers of the House (1964) departs from the Louisiana settings of her previous work. Set in Alabama, the novel revolves around the story of Abigail, whose grandfather, Will Howland, married Margaret, a woman of African American and Choctaw descent, and fathered three children by her. The three children are sent to the North because they can pass as white and thus enjoy the privileges of being white, including a better education. The eventual return of Will and Margaret’s son exposes racism in Abigail’s community.

Grau’s use of houses and the imagery of the home prevail throughout her fiction. In his study of four Grau novels, literary critic Anthony Bukoski argues that homes in Grau’s fiction can “alienate…when they become representative of the failure of the family to provide direction to its members.” Examples include Annie Landry, who leaves her home in The Hard Blue Sky, and Joan, who is locked out of her mother’s house at the end of The House on Coliseum Street.

Unlike her characters, however, Grau returns to her Louisiana home both physically and fictionally, adding a new dimension to literature through her detailed descriptions of Louisiana locations and the people who populate them.