Women Writers

Louisiana women have written about life in the state since before the Civil War, presenting their views of its unique society and landscape.

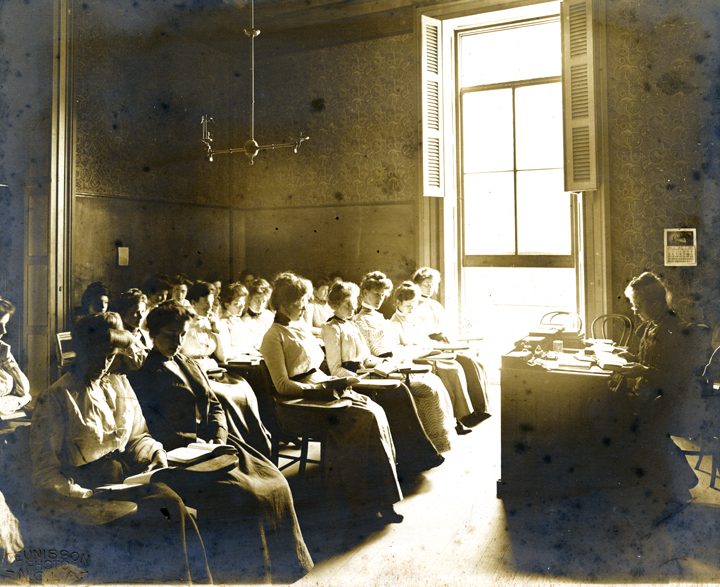

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

Classroom, H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College. Teunisson, John N. (Photographer)

Whether they were born in the state or settled in it, women have written about life in Louisiana since before the Civil War, presenting their views of the state’s unique society and landscape. Women writers in Louisiana reflected, reported, and contributed to the state’s distinctive literary heritage and complex social and political tensions. By examining and confronting the past’s links to the present, they laid a foundation on which contemporary authors continue to build.

Confederate diarists including teenagers Sarah Morgan Dawson, who recorded life on her family’s Louisiana plantation, and Clara Solomon, who documented urban life in antebellum New Orleans, contribute a unique and uncensored view of antebellum southern customs and politics. Later in the nineteenth century, Louisiana women such as Sidonie de la Houssaye wrote in French as well as English, recounting plantation life, travel, and social customs, as well as fictionalized accounts of love affairs, race relations, and politics. Long after the Civil War, however, Louisiana women continue to write about the social and political impact of race relations, as evidenced by the work of Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Shirley Ann Grau’s The Keepers of the House.

Louisiana Women Writers after the Civil War

As Louisiana’s former plantation owners fought to recover from the Civil War, women sought work that allowed them to maintain their “domestic responsibilities.” During Reconstruction, “over half of the newspapers in Louisiana had women writers; some [including the New Orleans Times-Democrat] were even edited by women.” In fact, the first woman in the world to own and manage a newspaper was New Orleans resident Eliza Nicholson, who saved the New Orleans Daily Picayune (the ancestor to today’s prize-winning Times-Picayune) from oblivion. Nicholson revamped the paper and hired female reporters and writers—including Elizabeth Gilmer ,who, under the pseudonym Dorothy Dix, dispensed advice to the lovelorn well into the 1940s. Other Louisiana women such as Miriam Follin Leslie, of Frank Leslie’s Lady’s Magazine, edited magazines owned by their husbands.

By the late 1800s and early 1900s, New Orleans women joined literary clubs like the Pan Gnostic League and Quarante, where members would review and respond to the papers other members presented. With support from other women, many female writers moved into the public sphere, while others wrote privately about the politics that heavily influenced their lives. Numerous nineteenth-century American women writers were earning money by writing and publishing, but New Orleans was home to a particularly large number of professional female writers.

At the turn of the century, many of these women writers—like their male counterparts—were influenced by local color fiction, a literary movement emphasizing the dialect and customs of specific places outside mainstream American culture. Keenly observant, these women wrote fictionalized accounts of southern life that included the unique dialects of blacks, poor whites, Cajuns, and Creoles, drawing attention to the things that made Louisiana seem different and exotic. New Orleans-born writer Grace King, educated at the city’s Institut de St. Louis and privately under the tutelage of a Madame Cenas and her daughter Heloise, infused her short stories for Century and Harper’s magazines with French phrases and Creole patois. Having studied with historian Charles Gayarré, King also contributed to a high school textbook on Louisiana history and eventually wrote a history of her hometown, New Orleans: The Place and the People.

Kate Chopin, who published stories about Cajun and French families, first lived in New Orleans with her husband before moving to a plantation in Cloutierville and then, after her husband’s death, back to her hometown of St. Louis, Missouri. While Chopin was a “lonely pioneer” in 1899, literary scholar Emily Toth suggests, she anticipated much of what was to come in the twentieth century, including “daytime dramas, women’s pictures, The Feminine Mystique, open marriages, women’s liberation, talk shows, Mars vs. Venus, self-help, and consciousness raising.”

Twentieth-Century Louisiana Women Writers

As women’s opportunities for higher education increased, female writers with more formal academic training emerged at the turn of the twentieth century. Newcomb College, the Louisiana Normal School (now Northwestern State University), and Straight College (now Dillard University) graduated journalists, fiction writers, and poets, including Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson, who wrote her first book of poetry in 1895. Louisiana lawyer Rose Falls Bres wrote plays about life as a professional in late nineteenth-century Louisiana, including The Law and the Lady Down in Dixie. Her first book, The Law and the Woman, explained the legal rights of women in every state. Published in 1917, the book was hailed by the New York Times as one of “unique value and interest.” Ada Jack Carver, who graduated from the Louisiana Normal School, began her award-winning writing career after she and her husband, a professor, moved from Natchitoches to Minden in 1920. Carver’s stories about Louisiana Redbones, people of mixed racial heritage, and the pioneers of the Cane River region, made her popular with readers of Harper’s and other magazines.

Mattie Ruth Cross Palmer moved to her mother’s hometown of Winnfield in 1957, and dedicated her papers to Northwestern State University when she died. Palmer had already seen two of her novels—A Question of Honor and The Golden Cocoon—made into movies popular in the 1920s. Palmer’s last book, The Beautiful and the Doomed, was written in Winnfield. After becoming a widow, Frances Parkinson Keyes moved to New Orleans, where she would write about Louisiana’s social conventions in historical novels such as Crescent Carnival and River Road. This prolific and best-selling author, whose work is suffused with Catholic religious principles, wrote most of her fifty-nine novels at her historic New Orleans home. Elma Godchaux, the descendent of a family of prominent Louisiana sugar refiners, won the 1936 O. Henry Prize and the support of literary critics for writing about race and social class in Depression-era Louisiana.

Louisiana women writers drew on the state’s rich cultural heritage, as well as its natural beauty. Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes was made into a popular and critically acclaimed film, nominated for eight Academy Awards. Set in the South after Reconstruction, the play’s themes of greed and class consciousness re-emerged throughout her nearly fifty-year writing career. Emilie Griffin, currently a resident of Alexandria, writes plays and stories about Catholicism and religious faith, having grown up in the predominately Catholic city of New Orleans. Alexandria-born writer Rebecca Wells describes the interactions and friendships of women living in central Louisiana in her Ya-Ya Sisterhood novels.

The first African American woman to earn a doctorate at Louisiana State University, Pinkie Gordon Lane, was the state’s poet laureate from 1989 to 1992. Lane’s later poems drew on what she identified as Louisiana’s “natural environment.” Like Lane, Mona Lisa Saloy, a 2006 PEN Award winner in poetry and director of creative writing at Dillard University, writes poetry about the attractions of New Orleans, her hometown, in the book Red Beans and Ricely Yours. Another writer shaped by New Orleans is Anne Rice, who, in recent years, has shifted her focus from vampires to Catholicism and Christian fiction.