Singer Submarine Company

The Singer Submarine Company operated a naval yard on the banks of Cross Bayou that built five Confederate submarines, four of which were sunk before seeing combat.

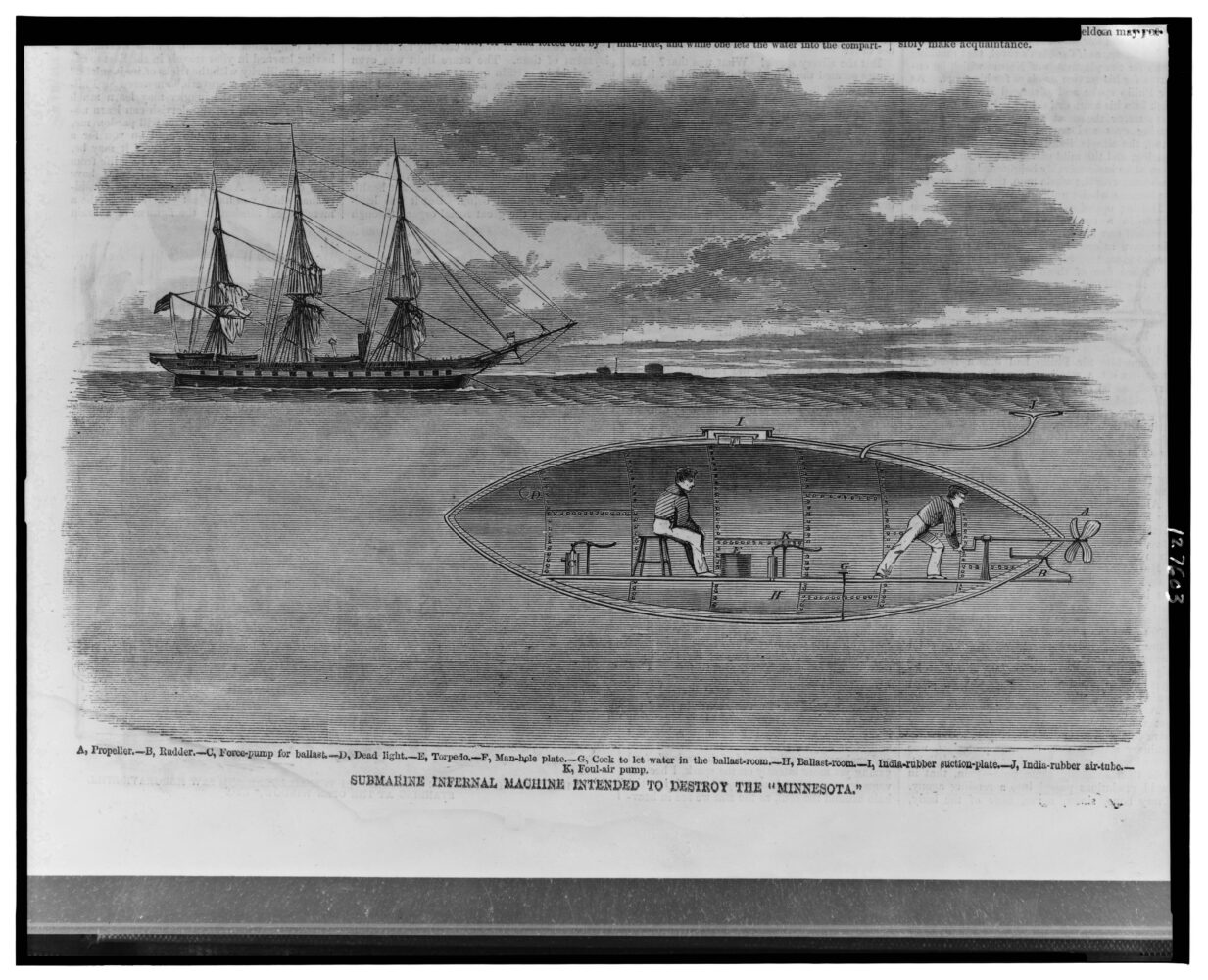

Library of Congress

An 1861 engraving from Harper's Magazine showing a Confederate submarine.

During the Civil War, the banks of Cross Bayou—where it meets the Red River in downtown Shreveport—were home to a naval yard operated by the Singer Submarine Company, which built submarines for the Confederacy.

The Singer Submarine Company was the creation of Edgar C. Singer of San Antonio, Texas. Singer was a mechanical engineer, who, together with a group of artillerists and engineers, built contact mines. The naval mines were the most widely used in the Confederacy, as were the torpedoes built by the firm.

Building Submarines

Three noted New Orleans inventors—Horace Hunley, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson—joined forces with Singer in 1863. These Louisianans had successfully built three submarines for the Confederacy: the CSS Pioneer and the Pioneer II, constructed in New Orleans, and the more famous CSS Hunley, built in Mobile, Alabama. On February 17, 1864, the USS Housatonic, a Union war sloop, became the first ship in American history to be sunk by a submarine when the Hunley attacked and destroyed her in the waters off Charleston, South Carolina.

After the sinking of the Housatonic, Confederate submarine operations took place in other locales, such as Mobile Bay, Alabama, and Norfolk, Virginia. Although their numbers were few—fewer even than Union experimental submarines then being created—Confederate submarines nevertheless struck a chord of fear in the North, with Harper’s Weekly describing them as “rebel infernal machines.”

Proved successful, the Singer Submarine Company was then engaged by the Confederate Navy to build many of its vessels at the naval yard in Shreveport, by then the capital of Confederate Louisiana. Several members of Singer’s submarine corps came to Shreveport in September 1863 to begin their work.

The naval yard was located on the southern bank of Cross Bayou where it meets the Red River. In the mid-nineteenth century the spot was a bustling industrial area with foundries, machine shops, and blacksmiths. Nearby, a short distance to the west, was the arsenal and magazine of the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederate Army, which was headquartered at Shreveport. It was at the Shreveport naval yard that two of the Confederacy’s famous ironclad warships were built: the CSS Webb and the CSS Missouri.

Workload and Vessel Specifications

Five submarines are known to have been built at Shreveport. Four never left town, but the other was sent to Houston, Texas. The Shreveport-built submarines were designed by James Jones, a Singer engineer who was also part of the inaugural crew of the Hunley; they were intended to play crucial roles in the destruction of federal ships on the Red River and elsewhere, but the war ended before they were called into combat.

A Union intelligence report from March 13, 1865, describes one of the Shreveport-built submarines. It states:

“The boat is forty feet long, forty-eight inches deep, and forty inches wide, built entirely of iron, and shaped similar to a steam boiler. The ends are sharp-pointed. On the sides are two iron flanges (called fins), for the purpose of raising or lowering the boat in the water. The boat is propelled at the rate of four miles per hour by means of a crank, worked by two men. The wheel is on the propeller principle.

The boat is usually worked seven feet underwater and has four deadlights for the purpose of steering or taking observations. Each boat carries two torpedoes, one at the bow, attached to a pole twenty feet long; one on the stern, fastened to a plank ten or twelve feet long. The explosion of the missile on the bow is caused by coming in contact with the object intended to be destroyed. The one on the stern, on the plank, is intended to explode when the plank strikes the vessel.

The air arrangements are so constructed as to retain sufficient air for four men at work and four idle, two or three hours. The torpedoes are made of sheet iron 3/16 of an inch thick and contain forty pounds of powder. The shape is something after the pattern of a wooden churn, and about twenty-eight inches long.”

Closure of Naval Yards

In June 1865 the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederate Army surrendered. Shortly thereafter a federal naval force was sent up the Red River to demand the surrender of the Missouri. To prevent four submarines from falling into Union hands along with the Missouri, the ships’ builders sank them in the muddy waters where Cross Bayou and the Red River meet. There they remain, buried in the river’s mud and silt, to this very day.