Solomon Northup

Solomon Northup, a free Black New Yorker, was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841, spending twelve years enslaved on Louisiana plantations before regaining his freedom.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

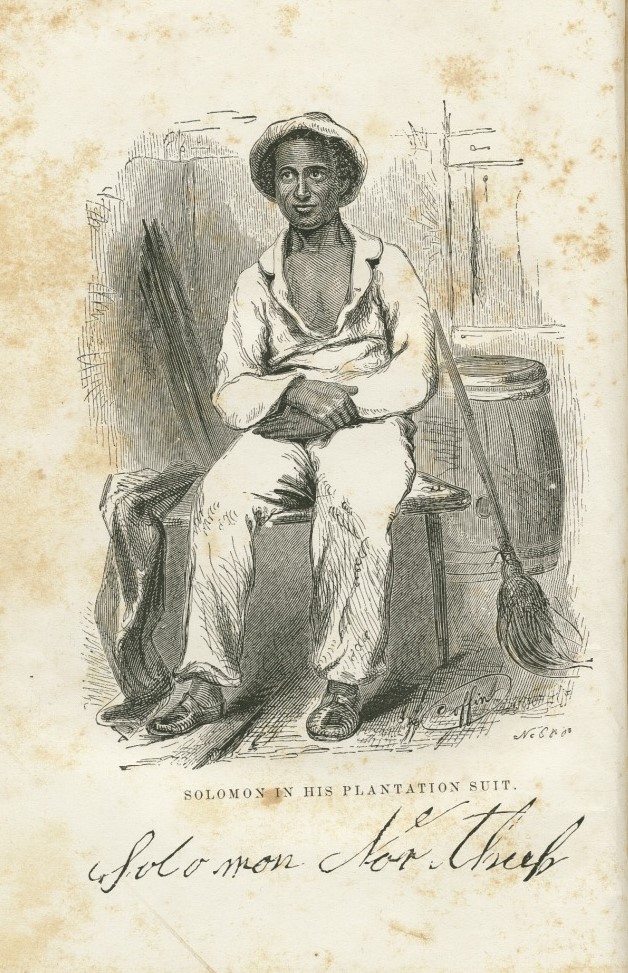

Frontispiece illustration of Solomon Northup by Frederick M. Coffin from Twelve Years a Slave.

Solomon Northup was a free Black man from New York who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in Louisiana between 1841 and 1853. Soon after escaping slavery he published his experiences as Twelve Years a Slave (1853). Northup’s autobiography has become an important source for understanding the history of the slave trade and slavery in Louisiana and the South.

Northup was born free in Minerva, New York, in July 1808. He grew up on farms in upstate New York, where his emancipated father, Mintus Northup, worked as a hired hand. In 1829 Northup married Anne Hampton; they had three children. During the 1830s he worked as a manual laborer and farm hand while supplementing his income during the winter by working as a traveling fiddler. In 1841 Northup met two men who called themselves Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton, who claimed that they worked for a circus and performed in Washington, DC. Promising large payments for performing with the circus, Brown and Hamilton lured Northup to the nation’s capital, where slavery was still legal. The two likely drugged him, and Northup woke up chained in a slave trader’s pen. He was no longer free but now the property of James H. Birch. As far as Birch was concerned, Northup was an escaped enslaved person from Georgia whom Brown and Hamilton had captured. Birch boarded Northup and other people he enslaved on a ship to New Orleans, part of the domestic slave trade.

In New Orleans Northup again spent time in a slave trader’s pen, this time that of Birch’s business partner Theophilus Freeman. With Freeman, Northup learned that he had been assigned the name Platt Hamilton, likely to disguise his identity. After Northup survived a bout of smallpox, Louisiana enslaver William Ford purchased Northup from Freeman. Northup spent most of his twelve years enslaved in Avoyelles Parish, on Ford’s plantation, or on the plantation of Edwin Epps, who purchased Northup in 1843. Northup labored in cotton fields during most of the years he was enslaved to Epps, but he was also sent to sugar plantations after the cotton harvest. Northup’s intelligence, musical abilities, and woodworking and lumbering skills distinguished him in the eyes of his enslavers. While enslaved, Northup frequently sought ways to escape but was unsuccessful. He was also well acquainted with the violence that upheld and enforced slavery.

Northup’s most significant opportunity to escape came in 1852, when Epps decided to build a new home. Epps employed a carpenter from Canada named Samuel Bass to construct the building and assigned Northup to assist. Bass was vocal about his antislavery opinions, and Northup eventually confided in the carpenter. Bass mailed a letter Northup had secretly written and sent others on his behalf to Northup’s white acquaintances in New York. After four months and with the aid of New York’s governor and attorney general, the son of the man who had enslaved Northup’s father—Henry Northup—arrived in Avoyelles Parish to free Solomon Northup. Since the letters Bass sent were postmarked in Marksville, Henry Northup was able to track down the Canadian, who led him to Epps’s plantation. Solomon Northup returned to New York a free man. On his way home he filed lawsuits in Washington and New York against the men who enslaved him, though both cases were dropped by 1857.

Soon after his return Northup dictated Twelve Years a Slave with help from local lawyer and politician David Wilson. The autobiography became a bestseller, appearing just a year after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). Northup began touring abolitionist circuits to tell his story of enslavement, a common practice of formerly enslaved Black abolitionists. By the late 1850s Northup disappeared from the public, likely because he died. Unfortunately no record of his death or grave has ever been found.

Northup survived the domestic slave trade and slavery in Louisiana. His autobiographical account informed abolitionists’ attacks on slavery, and he lectured at antislavery meetings. Today educators continue to assign his published account in classrooms across the United States for its stark depiction of enslavement.