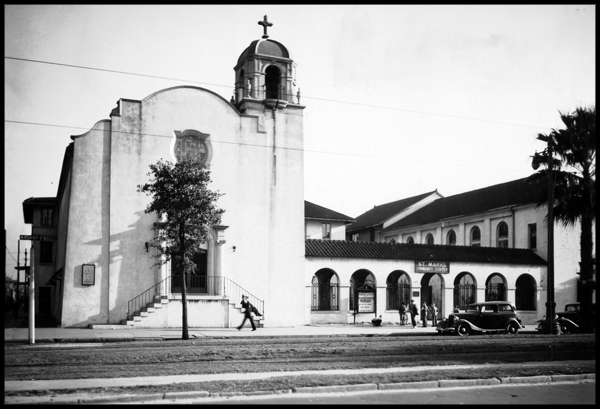

St. Mark’s Community Center

St. Mark's Community Center, a settlement house run by Methodist deaconesses, opened its doors in New Orleans in 1909 and continues to operate today.

Courtesy of State Library of Louisiana

St. Mark's Community Center in New Orleans. Barkemeyer, Erol (Photographer)

St. Mark’s Community Center, a settlement house run by Methodist deaconesses and originally known as St. Mark’s Hall, opened its doors in New Orleans in 1909 and continues to operate today. Originally located on Esplanade Avenue, the house was a classic expression of the social gospel, a late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century movement among Protestants to address societal problems arising from the surge of industrialization, urbanization, and immigration. St. Mark’s also served as a bastion of progressive thought and action during the women’s suffrage movement of the 1910s and the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

The women who operated St. Mark’s offered spiritual training to thousands of New Orleanians; provided wholesome recreation for youth; fostered the educational and leadership development of immigrants, particularly women; pioneered free health care to the needy; and offered child care for working mothers and instruction for child care providers long before these services were commonly available. For decades St. Mark’s was also the only location in New Orleans where mixed race groups of any sort could hold meetings. Currently owned by the Women’s Division of the United Methodist Church, South (MECS), the center reorganized after Hurricane Katrina as the North Rampart Community Center. It is presently located at 1130 North Rampart Street.

The Mary Werlein Mission

St. Mark’s grew out of the Mary Werlein Mission, an organization run by the Woman’s Parsonage and Home Mission Society (WPHMS) and located in New Orleans’s Irish Channel neighborhood. In addition to providing a place for street preaching and evangelism, the Werlein Mission carried out urban ministries under the direction of Lillie Meekins, a city missionary from Covington. In residence at the mission, Meekins was surrounded by mills, factories, and the tenements where poorly paid laborers lived. She was determined to improve the lives of those around her. Mary Werlein, the mission’s primary fund-raiser and a leader within the WPHMS, spent her time working for the church, leading religious services in jails, and participating in activist women’s organizations, especially those concerned with providing safe housing for single women.

Believing that it was not reaching enough immigrants—particularly the recent wave of Italian arrivals—the WPHMS expanded its work into the French Quarter in 1909. Under the leadership of Deaconess Margaret Ragland, the first head resident at St. Mark’s, programming included classes in English, sewing, and cooking. Because many in the community suffered from preventable or treatable illnesses, St. Mark’s provided a free clinic for women and children, staffed by a resident nurse deaconess and a female physician who volunteered her time. The women also ran several industrial schools that provided job skills for young people, a night school that offered elementary education for adults, and clubs for adults and children.

Ragland and other deaconesses saw their task as both true settlement work and evangelistic Christian mission, though conversion to Methodism was not required of St. Mark’s clients. On Sunday evenings St. Mark’s welcomed visitors for a courtyard worship service that was attended by people from twenty-five countries. This “Church of All Nations” held services in both Italian and English.

Local Lay Leaders

The local Methodist women responsible for St. Mark’s establishment were led by Elvira Beach Carré, a widow and mother of seven who successfully managed her husband’s lumber mill after his death. She also served as the president of six local organizations at one time, including the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA), which she helped bring to the city, and the City Mission Board. Her successor, Hattie Rowland Parker, was an activist and leader of the Era Club, a group devoted to women’s suffrage. Before coming to the settlement house, Parker advocated the establishment of a separate court for juvenile offenders, the abolition of child labor, and efforts to reduce infant mortality. Both Carré and Parker also played active roles in the woman suffrage movement, working for women’s right to vote in political elections and within the Methodist church.

Although some settlement houses were identified with one individual—Hull House in Chicago, for example, was associated with Jane Addams, and Kingsley House in New Orleans with Eleanor McMain—the Methodist women pooled their individual talents and resources into a collaborative effort. Their endeavors required both deaconesses, who worked full time and possessed training and professional expertise, and laywomen, who raised funds and built local networks. Together these women created a community of individuals who understood and appreciated each other’s abilities and commitments to social change.

The Methodist Deaconess

During the settlement movement, well-educated individuals often chose to live among poor and/or immigrant peoples in order to better understand their needs. Deaconesses were trained in theology as well as in community and social justice issues at Methodist academies. Part of their mission at St. Mark’s was to become integral to the neighborhood.

The MECS consecrated its first deaconesses in 1903. In exchange for full-time work, deaconesses received room and board, plus a small allowance to cover other needs, including the required uniforms (long black dresses and bonnets tied with a white bow). This uniform was made optional in 1925, not long after the settlement moved to a facility located on North Rampart Street at Gov. Nicholls Street. Named the St. Mark’s Community Center, this structure was one of the finest settlement facilities in the South. Along with a full gymnasium, an indoor swimming pool, and ample space for classes and club work, it had a very well-equipped medical and dental clinic. The clinic helped break down opposition to the center’s work by the conservative male leadership of the MECS, who considered the women engaged in settlement work as too secular; its service and follow-up visits by the nurse deaconess brought most of the newcomers to worship and other center services.

The MECS women’s goals included helping immigrants adjust to life in America. To help women preserve their ethnic heritage, settlement workers encouraged them to showcase their food, crafts, and culture. At the same time, they helped the newcomers learn English and become citizens—services much in demand in the community.

The congregation and the community center separated administratively in 1925, when the city’s Community Chest (now the United Way) organized and began providing financial assistance to St. Mark’s. The congregation and center continued to share space in the building, and St. Mark’s United Methodist Church still worships there.

Work for Racial Equality

Most deaconesses who served at St. Mark’s were trained at Scarritt College in Nashville, Tennessee, and many were influenced by a professor who was a prominent white member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In addition to relating the teachings of Jesus to contemporary social ills, the Scarritt curriculum addressed problems related to unchecked capitalism. Similarly, in their Methodist women’s study groups, New Orleans laywomen such as Werlein, Carré, and Parker frequently read the work of social gospel literature concerned with issues of class, race, and economic disparity.

As early as 1917, the leaders of St. Mark’s called for education about race and tolerance of racial minorities. Their grounding in the social gospel and their powerful religious beliefs allowed them to push for real social change, even when it put them in conflict with their segregated and sexist society. At the St. Mark’s clinic, for example, patients—black and white—used the same dental chairs and medical examining rooms, at a time when Jim Crow laws dictated that these facilities be segregated.

Although by today’s standards, some of the women’s efforts can be legitimately criticized as racially insensitive, they were on the cutting edge of race relations at the time. Critics castigated the white women simply because they raised funds to establish black settlements in black neighborhoods, and because some white deaconesses, including some who served at St. Mark’s, chose to work at those settlements. White Methodist laywomen held meetings with black women’s groups to address racism. Like other white MECS women’s societies, the New Orleans local chapters studied literature on race and attempted to improve race relations; they also called for voting rights for blacks in the early 1950s.

The MECS women laid groundwork that allowed St. Mark’s to play a major role in the New Orleans School Crisis. In 1960 the worshipping congregation, with the deaconesses and active lay leaders, supported pastor Lloyd Anderson “Andy” Foreman when he and his daughter, Pamela, broke the white boycott of William Frantz Elementary that began when six-year-old Ruby Bridges began attending the school as its first black student. In response, St. Mark’s was vandalized, and the Foremans and the center staff received numerous death threats. Fae Daves, the last deaconess to serve St. Mark’s until after Hurricane Katrina, and longtime employee Laura Smith saw the center through its own full integration in the 1960s. The first time Smith took African American children from the city to the center’s camp on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, a cross was burned at the campgrounds.

Religion guided the actions of the women of St. Mark’s, even when it put them in conflict with the values of their segregated and sexist society. The civil rights movement, the social gospel movement, and the push for women’s ordination in the Methodist Church all benefited from their courageous work.