Thibodaux Massacre

The Thibodaux Massacre was the resulting violence of a three-week strike in the sugar-producing region of Lafourche, Terrebonne, St. Mary, and Iberia parishes.

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

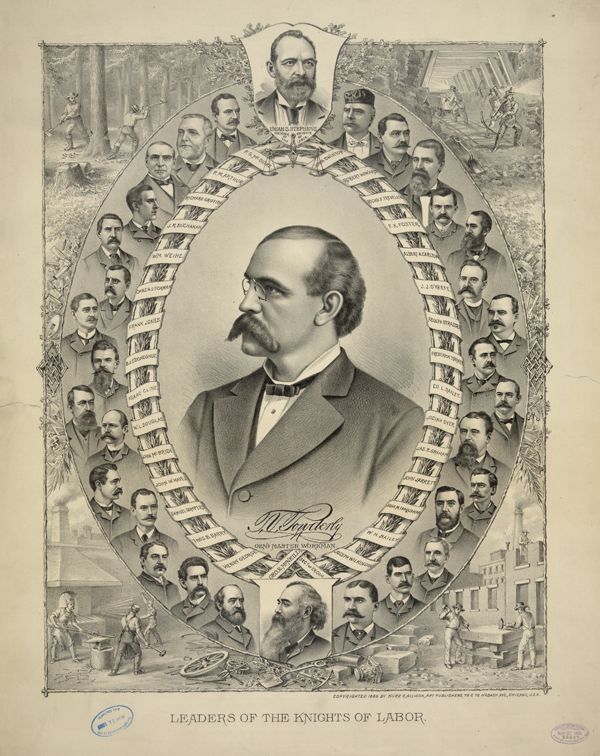

Leaders of the Knights of Labor. Kurz & Allison

Editor’s Note: Warning, this entry contains graphic imagery.

The Thibodaux Massacre, which took place on or about November 22, 1887, resulted from a three-week strike in the sugar-producing region of Lafourche, Terrebonne, St. Mary, and Iberia parishes. This confrontation is known as the second bloodiest labor dispute in U.S. history, although the actual number of fatalities remains uncertain. What began as a disagreement over wages became an expression of racial tensions that had been building since the dissolution of slavery. When the bloodshed ended, at least thirty-five and as many as three hundred African American workers had been killed at the hands of local white vigilantes.

Organization of Sugar Plantation Workers

The Sugar Strike of 1887, which preceded the massacre, differed from previous labor protests in the region in three ways: wage distribution, organization, and timing. Not only did workers and planters disagree on the amount of payment for labor, but also the method by which payment was made. Freedmen opposed the use of scrip or coins to be redeemed only at the plantation store. Plantation owners determined the pricing of goods. If a worker became indebted to the plantation store, he was required by law to stay and work until the debt was paid. This forced freedmen to remain at that plantation, continuing, for all intents and purposes, the enslavement from which they had recently been freed. Opposition to plantation scrip gave workers a powerful cause to unite them in protest.

In 1886, The Knights of Labor formed Local Assembly 8404 in Shreveport for the purpose of organizing sugar plantation workers. There had been minor protests before, but this was the first time that a structured labor association had operated in the region. In October 1887, the Knights of Labor presented a list of demands to the Louisiana Sugar Producer’s Association, including the elimination of scrip, a small increase in wages, and biweekly payments. When their demands were ignored, the Knights of Labor called for a strike to begin on November 1, 1887. On that day, an estimated ten thousand sugar plantation workers united in a work stoppage that affected the entire region. The precise number of strikers is not known, but there is no question that the Sugar Strike of 1887 was a major event.

The Sugar Strike of 1887

The strike was scheduled to begin at the most important time in the sugar plantation year. The “rolling season,” or sugar harvest, was a complex process requiring fine coordination, intensive labor, and perfect timing. If the sugar cane was not brought in on time, the impending frost would ruin the crop. If the sugar mill was unable to function smoothly, the cane could not be processed properly, and a fortune in profits would be lost. The workers used their knowledge of the intricacies of the harvest as leverage, forcing the planters to negotiate or risk sustaining heavy losses.

On November 1, the sugar plantation workers refused to bring in the crop. Alarmed by the prospect of losing their crops, planters asked Governor John McEnery to intervene and send the state militia to the sugar parishes. The governor, who was also a planter, agreed to deploy the militia to the region. Soldiers evicted striking workers and protected the scabs, or strike breakers, who took their jobs. The displaced workers and their families moved to the overcrowded African American section of Thibodaux. After establishing its initial presence, the militia left the area and the responsibility of maintaining order fell to the local leadership.

As the threat of frost increased, tensions between idle plantation workers and hostile white townspeople escalated. When the news spread that a few white scabs had been fired upon, hostility between races grew. White civilians formed pickets, protesting the strikers’ violence, while displaced plantation workers became even more confrontational. Judge Taylor Beattie, of Orange Grove Plantation, led the Peace and Order Committee in Thibodaux. The committee decreed that blacks within the city limits would need to show a pass to enter or leave. On the morning of November 22, armed members of the committee closed the entrances to the city, leading some of the black strikers to believe that they were endangered. After two of the white guards were fired upon, an explosion of racial violence ensued. During the chaotic hours of the massacre, black strikers and their families were rounded up by bands of local vigilantes and shot on sight.

In her writings, plantation mistress Mary Pugh indicated that “the initial skirmish commenced what soon became a frenzy of violence against the strikers. White guardsmen began hunting up the Leaders, and every one that was found or any suspicious character was shot.” When the violence ended, demoralized workers returned to the plantations to resume the sugar harvest. The workers were so solidly defeated that no attempt was made to organize sugar workers in Louisiana again until 1950. Pugh predicted that the massacre would “settle the question of who is to rule, the nigger or the white man, for the next fifty years, but it has been well done and I hope that all trouble is ended.”

The Thibodaux Massacre demonstrated the difficult transition from slavery to the new era of free labor. What began as a labor dispute erupted into a violent racial battle. For the planters who had witnessed great change after the Civil War and who were enduring economic hardships, the incident represented a battle to maintain some semblance of their eroding authority. For the freed sugar plantation workers, it was a fight to establish a sense of the power that had been denied them for generations. Neither side saw any means of compromise, and the interdependent nature of the sugar-planting industry led to an inevitable conflict. Ironically, the freedmen’s attempt to assert their newly granted rights resulted in more planter control. For many years after the Thibodaux Massacre, workers were even more dependent on the planters who had previously enslaved them.