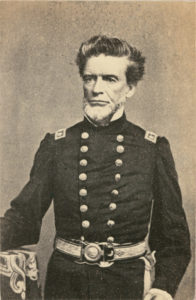

Thomas Overton Moore

Thomas Overton Moore served as the fourteenth governor of Louisiana, leading the state through much of the Civil War.

Courtesy of Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University

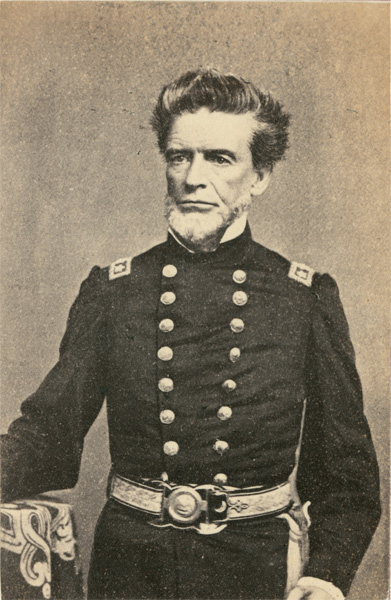

Thomas Overton Moore. Unidentified

As the fourteenth governor of Louisiana under American rule, Thomas Overton Moore served under the Confederacy, leading the state through much of the Civil War for the last three years of his term (1860–1864). After his inauguration in January 1860, Moore initially favored a peaceful boycott of Northern goods over secession as a way to protect slavery. Nevertheless, after Abraham Lincoln’s election in November of that year, he announced, “I do not think it comports with the honor and respect of Louisiana, as a slaveholding state, to live under the government of a black Republican.” Moore became a strong advocate of secession, and preemptively ordered the seizure of federal forts and arsenals before the Ordinance of Secession was enacted on January 26, 1861. Unlike other governors of Confederate states who took an extreme position on states’ rights, Moore tried to strike a balance between supporting the Confederate government and the needs of his home state.

Thomas Overton Moore was born in Sampson County, North Carolina, on April 10, 1804. In 1823 he moved to Rapides Parish to work as an overseer for his uncle, General Walter H. Overton, a veteran of the War of 1812 and staunch Jacksonian Democrat. In 1830 he married Bethial Jane Leonard, who bore him five children. Moore acquired plantations of his own, including his wife’s prodigious inheritance of a plantation and slaves. He prospered, and in the antebellum tradition of “government by gentlemen,” he entered politics as a loyal member of the wing of Louisiana’s Democratic Party controlled by then-US Senator John Slidell. Moore was elected to the state House of Representatives and in 1856 won an election to the state Senate. In 1859, John Slidell handpicked Moore to run for governor, and he defeated fellow Rapides Parish planter Thomas Wells, who had the support of the Know-Nothings (a nativist American political movement of the 1840s and 1850s empowered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by German and Irish Catholic immigrants) and old Whigs (a party formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson).

Moore faced a number of obstacles as a wartime governor. Louisiana more than fulfilled its quota of troops for distant battlefields in Virginia and Tennessee, but such deployments left a paucity of troops to protect the state. Arms and ammunition that Moore purchased for Louisiana were confiscated by Earl Van Dorn, Confederate commander of the Southern Mississippi and East Louisiana District, and not returned in spite of an order by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Moore unsuccessfully tried to prohibit the sale of cotton to the enemy, a practice that was rampant throughout the war.

After both New Orleans and Baton Rouge fell to the Union army and navy in 1862, Moore moved the state capital to Opelousas and then to Shreveport. Once the Union army fully occupied the bottom third of Louisiana, Moore focused his efforts on salvaging West Louisiana, since this area was essential for providing Confederate armies with supplies from Texas and Mexico. In order to protect the region, Moore tirelessly lobbied Jefferson Davis for a separate Louisiana command within the Trans-Mississippi Department, and Davis, once convinced, transferred Richard Taylor (son of Zachary Taylor and a Louisiana native) from Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia to command the Confederate Army in Western Louisiana. Moore’s efforts were vindicated when Taylor’s army soundly defeated Union troops under the command of Nathaniel Banks, commander of the Department of the Gulf, at the Battle of Mansfield, south of Shreveport, in 1864. The decisive battle thwarted a Union invasion of Texas.

Moore was a staunch defender of slavery as a positive good. When US Gen. Benjamin Butler gained support among Union sympathizers in New Orleans by courting white labor with anti-planter rhetoric, Moore countered with a public letter: “The workingmen of the South know full well that that this war on the part of the North is not so much against the institution of slavery as it is against its influence upon labor. Men get better prices for their services where it exists.” After Moore decided against a second term, he considered leaving Louisiana and taking his slaves to Mexico with the intent of starting over, since his own plantation was in ruins. Nevertheless, Mexican law would have freed his slaves and he abandoned the plan.

After Confederate Gen. E. Kirby Smith surrendered the Trans-Mississippi Department in Galveston, Texas, on June 2, 1865, Moore escaped to Havana, Cuba, via Mexico, fearing that he would be tried as a war criminal. On January 15, 1867, Moore received a full pardon from President Andrew Johnson. Moore returned to Rapides Parish, where he died at his home near Alexandria on June 25, 1876. He is buried at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Pineville, Louisiana.