Willie Piazza

Willie Piazza was one of the most successful madams in the Storyville vice district of New Orleans until it was closed in 1917.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

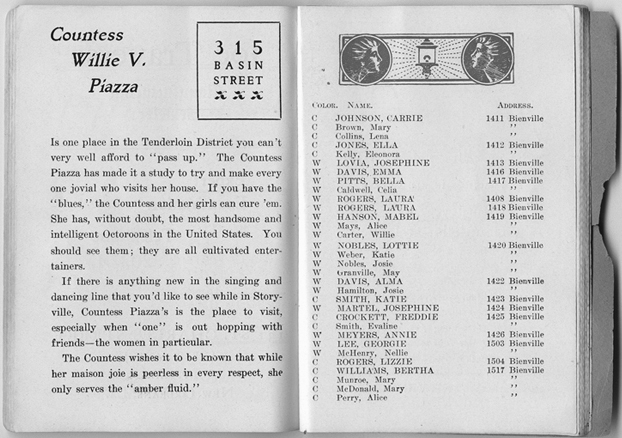

Advertisement for Countess Willie Piazza's. Basin Street Publishing Company ( publisher )

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Willie Piazza was one of the most successful octoroon madams in Storyville, the vice district of New Orleans. Promoting interracial racial sex in the era of Jim Crow eventually earned Piazza the city’s condemnation, but not before she made enough money to buy and furnish an upscale brothel. Moreover, when the city attempted to segregate Storyville and shut down her operation, Piazza took her case to the Louisiana state supreme court—and won.

Willie Vincent Piazza was born about 1865 in Jackson, Mississippi, to Celia Caldwell and Vincent Piazza, unmarried teenagers. Census data provide few clues about her parents’ background, other than revealing that her mother was classified as black and her father as white. Evidence suggests that her father was the son of Italian immigrants. By 1880, Celia Caldwell was “keeping house” in Jackson with Willie and two siblings, while Vincent Piazza had moved to Vicksburg, where he became a hotel proprietor. Not much is known about Piazza before she arrived in New Orleans, some time in the 1890s, except that she was either experienced or well positioned enough in the sex trade to become the madam of her own house by 1898.

Whatever the specifics of her racial heritage, Piazza identified herself and the women who worked in her brothel as octoroons. This racialized descriptor combined the eroticized associations of antebellum quadroon women with a slightly whiter genealogy. Despite the strict racial segregation outside Storyville, Piazza and other octoroon madams and prostitutes thrived within the district. They became one of Storyville’s major and most notorious attractions among their exclusively white male clientele. This did not escape the notice of reformers, who leveled withering criticism at the district generally but saved their strongest invective for octoroon women like Piazza. Despite the criticism, Piazza prospered and used her substantial profits to purchase a building at 317 N. Basin Street, Storyville’s main thoroughfare. She paid the building off in two years and, like other prominent madams, furnished her brothel in “an elaborate and expensive manner.”

Local politicians protected Storvyille and the enormous graft it generated, but on the eve of World War I, federal officials aimed to shutter the district to protect soldiers from venereal infection. In order to save Storyville, local officials attempted to segregate the vice district on the basis of race. Piazza and other women of color resisted their ouster, and more than two dozen women of color filed suit. Piazza’s case went to the state supreme court, where she won a surprising victory, but her triumph was short lived. In late 1917, shortly after the case was settled, federal officials forced the city to shutter the vice district entirely.

After Storyville’s demise, Piazza continued to live in her Basin Street property. She also traveled abroad, sailed to the Caribbean on her yacht, accumulated real estate, and lived out her life in a quiet but dignified fashion. On November 2, 1932, she died of cancer in New Orleans, leaving behind a substantial estate.