Sarah Morgan Dawson

Sarah Morgan Dawson kept a dairy of her experiences during the Civil War in Louisiana.

Courtesy of University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

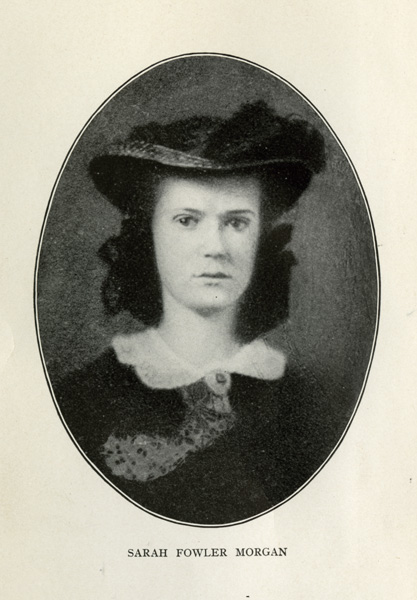

Sarah Morgan Dawson, 1842-1909. Unidentified

Nineteenth-century Louisiana writer Sarah Morgan Dawson is best known for the diary she kept during the Civil War. From March 1862 until April 1865, Dawson chronicled her thoughts and experiences, providing one of the most detailed accounts of civilian life in wartime Louisiana. A gifted storyteller, Dawson recorded her feelings about the Confederacy, war, politics, refugee life, and women’s place in society against the backdrop of Louisiana’s invasion and occupation by Union troops.

Born in New Orleans on February 28, 1842, Sarah Ida Fowler Morgan was the seventh child of Judge Thomas Gibbes Morgan and his second wife, Sarah Hunt Fowler. In 1850, the family relocated to Baton Rouge, where Thomas worked as a district attorney and later a district judge. After less than a year of formal education, Dawson studied under the tutelage of her mother at the family home on Church Street. Her comfortable home life began to unravel at the beginning of the Civil War.

Civil War Diary

In April 1861, Dawson’s brother, Henry Waller Fowler Morgan, died in a duel. Later the same year, her father—who opposed secession but supported his state once it seceded—died at home. When Dawson began her diary in January 1862, she was still mourning the loss of her kin in addition to the departure of her three remaining brothers—Thomas Gibbes Jr., George Mather, and James Morris Morgan—to the Confederate army and navy. In Baton Rouge with her mother and sisters, Dawson recorded the scarcity of food and household items as a result of the Union blockade, remarking that “Confederate” amounted to anything that was “rough, unfinished, unfashionable or poor.”

In April 1862, David Glasgow Farragut captured New Orleans, and by May, the Federal onslaught on Baton Rouge had begun in earnest. With her “running bag” packed and her personal papers piled on her bed ready to burn, Dawson used her diary to record a warning to any Federal soldier who attempted to “Butlerize—or brutalize” her in the attack. “I will show you the use of a small seven-shooter,” she wrote, “and large carving knife which vibrate between my belt, and pocket, always ready for use.”

Within days of the attack, Sarah, her mother, and her sisters, Miriam Antoinette Morgan and Eliza Ann Morgan LaNoue, were forced to abandon their home for safer quarters in Clinton. Inhabiting a sparsely furnished one-bedroom apartment, Dawson documented the hardships of refugee life. In August 1862, Dawson accepted an invitation from her sister-in-law, Lydia Carter Morgan, to visit the Carter plantation, Linwood, in East Feliciana Parish. At Linwood, she wrote about her isolation from the privations of the war, and the frequent visits by groups of Confederate soldiers encamped at nearby Port Hudson.

Dawson’s visit to Linwood was extended after she was thrown from a horse in November 1862 and spent months incapacitated by a back injury. The federal assault on the Confederate stronghold at Port Hudson in July 1863, however, forced the Morgan women to make a final exodus to occupied New Orleans, where they joined the household of Dawson’s half-brother and Unionist sympathizer Judge Philip Hicky Morgan. While in his home, Dawson received news of the death of her brothers, Gibbes and George, in February 1864.

Life after the Civil War

Without an independent fortune, Dawson spent the late 1860s as a dependent in Philip Morgan’s household. In May 1872, Dawson and her mother moved to South Carolina to make their home with Sarah’s younger brother, James. In an effort to support herself, Dawson accepted an editorial position at the Charleston News and Courier, and throughout 1873, she wrote a series of editorials on the plight of young, single women in the postwar South. In 1874, Dawson married the newspaper’s editor, Englishman Francis Warrington Dawson. The couple had three children: Ethel in 1874, Warrington in 1878, and Philip Hicky in 1881. Philip died at six months of age. After her husband’s murder in 1889, Dawson again turned to her pen for survival, publishing a series of short stories and translations of French literary works. In 1899, Dawson moved to Paris with her son Warrington, where she published Les Aventures de Jeannot Lapin, a French version of the Brer Rabbit stories, in 1903. She died in Paris on May 5, 1909.

Though Dawson originally asked that her six-volume diary be destroyed upon her death, she later willed it to her son Warrington. In 1913, he arranged to have the first four volumes published as A Confederate Girl’s Diary. The diary was later edited by Charles East and published in its entirety in 1991. Dawson’s correspondence with her future husband, Francis Warrington Dawson, has also been published.