Spring 2016

Excavating the Mysteries of Poverty Point

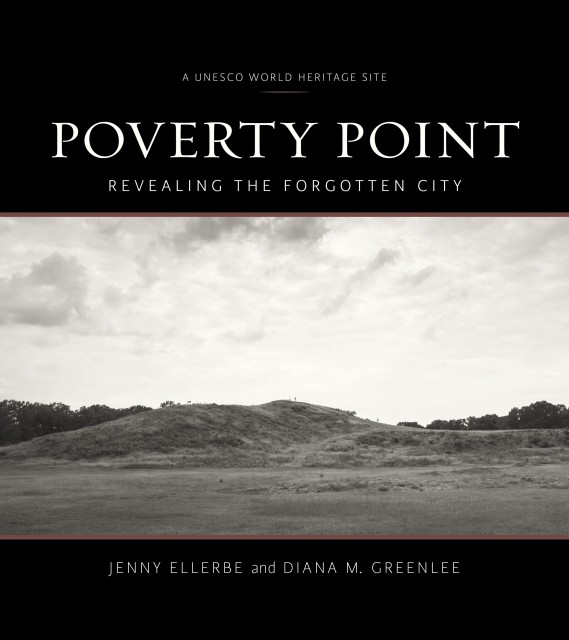

2016 Humanities Book of the Year features two distinctive voices

Published: March 1, 2016

Last Updated: January 14, 2019

Photo by Jenny Ellerbe

This veneration for such places inspires one of the LEH’s 2016 Humanities Books of the Year: Poverty Point: Revealing the Forgotten City by Jenny Ellerbe and Diana Greenlee (Louisiana State University Press, 2015). A 345-acre site in northeastern Louisiana, just 20 minutes off I-20, Poverty Point is probably more than 3,000 years old. Over the centuries, farming, erosion, and road making have taken their toll, flattening and obscuring what must have once been even more conspicuous features in the landscape. The authors describe Poverty Point as “the New York City of its day, rising above all others in North America.” Today, there are six mounds and more than five miles of man-made ridges rising above Macon Bayou. The National Parks Service manages the site and artifacts and other “Poverty Point Objects” can be seen in its museum. The original function of the latter may not even be known, but help in assigning dates to the pre-agricultural society that made the mounds. Poverty Point was designated a National Monument in 1988, and in 2014, thanks largely to the help of the book’s two authors and the State of Louisiana’s Office of Cultural Development, it became Louisiana’s first World Heritage Site as approved by United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

Revealing the Forgotten City emerged from the documentation process required for the UNESCO nomination in 2013. The authors present the sum of what is known about the site, acknowledging past theories and exploring current issues in an accessible blend of technical data, photographs, and narrative. What makes this a different kind of history book is the two distinct styles of Greenlee and Ellerbe, who take alternating sections of the text. Greenlee writes from the standard scholarly point of view, presenting verifiable information with clear data and references. Ellerbe creates a more lyrical approach that attempts to convey the wonder and strangeness of Poverty Point and to make a thoughtful connection of some kind with the people who inhabited it.

Dr. Diana Greenlee, the station archeologist, presents her material in a mostly third-person, objective account of the site excavation. Charts and colored photographs illustrate the results of geophysical surveys, magnetic gradiometers, and the laser-sensing technology known as LiDar which produces topographic maps. Greenlee uses these to build up a picture of how to examine the culture that built the mounds. She compares Poverty Point evidence like middens, post-holes, and decorative artifacts with other finds from mound sites across the eastern United States. Her text describes the techniques used to study and classify the site over the 300 years since Europeans first noticed the mounds, together with the conclusions they have drawn, and then shows how some of these inferences have been erroneous.

In 1927, for example, an archeologist from the Smithsonian Institution concluded that the mounds were natural formations, not man-made. To counter this, Greenlee demonstrates how modern soil-sampling assesses the diversity of materials within the mounds, which, together with radio-carbon dating, indicates that the soil was brought in baskets to the site (the impressions of some of which can be seen, astonishingly, in a few of the photographs). She then goes on to calculate how many baskets of earth it would take to build the 72-feet high Mound A: 15.5 million loads! Having established that Paleo-Indians did in fact raise these mounds, Greenlee describes them in the context of the culture of the other Middle-Archaic “mound-builders” and provides the reader a helpful background as to why these people might have used up precious resources of time and energy to build ”cultural elaborations” that may not have had a specific function. She explores the number of spear-points (sometimes wrongly called “arrow-heads” by casual collectors), which remind us that these people were hunter-gatherers and lived in a time before agriculture was practiced. All of her data is presented in clear, readable prose with timelines and illustrations to help us locate the civilization which built Poverty Point in our knowledge of world history.

Interspersed with all this fascinating archeological detail is photographer Jenny Ellerbe’s personal story about her relationship, as it were, with Poverty Point, a place she has known since childhood. She became involved in the UNESCO bid as an official photographer, but in this book she brings an artist’s eye to the site and rounds out the archeological study with a first-person narrative about the effect Poverty Point has on a creative, imaginative sightseer. This deliberate subjectivity mediates past with present in almost poetic terms. Here she tells us about walking on Mound E:

I walk through acres of dry, cut grass that rests like tufts of hay on the soft ground. All is beige and dormant. From the empty expanse of ocher, a dozen small birds rise before me, as if they were born of the brownness and released at the sound of my footsteps. I walk on, and it happens again and again. From nothing, from the grass . . . flocks of birds. And so the Poverty Point people appear before me at times, when I least expect them, when I am walking their city, when they rise from seemingly nowhere.

Ellerbe’s narratives are accompanied by stirring black-and-white photographs that represent the landscape: they show the mounds not just in the clear light of science but in dawn mists or through a beautyberry bush. As she says of her fellow author in the Prologue, “the book is structured much like our conversations—my wanderings and musings, her research and data.” Ellerbe goes on to point out that these two perspectives attempt to enhance our view of Poverty Point as “a city and culture to be experienced.” The images she contributes offer a wordless impression of the site as it stands today.

One of the strongest sections in the book describes the people of Poverty Point through their artifacts, the small hand-shaped objects used for hunting, cooking, or decoration that are “diagnostic” as they tell us about the daily lives of the people who lived amongst the mounds. Because there are no naturally found rocks at the site, the many microliths—the small tools made of stone—must have been brought from elsewhere, like the plethora of decorative objects made from materials like galena and hematite. This section of the book is illustrated with many clear photographs of these objects and some of them summon the past powerfully. Little pot-bellied owl pendants of red jasper are found all over the Southeastern U.S., but the ones from Poverty Point look particularly appealing with their “miniature feet, curved beaks, and drilled eye cones.” The human figures in clay also claim a connection with us; there is a photograph of a small head which seems, as Ellerbe points out, to have been captured in the act of speaking “as if caught in mid-sentence, the eyes empty but still somehow seeing.”

The two authors create a right-brain/left-brain approach to Poverty Point that produces a book to please all readers. It is handsome enough to sit on a coffee-table, yet also scholarly enough to answer contextual questions about the history and geography of the site. To add to its academic bona fides, the book includes a full list of references and further reading, as well as a very useful glossary at the back of the book to define terms like “pedogenic” and “atlatl” for the lay reader whose knowledge of the science behind archeology and anthropology is slight. Poverty Point: Revealing the Forgotten City well deserves its status as an LEH Book of the Year: it is interesting, informative, and beautiful to look at. And I hope that it brings readers to visit the site for themselves. As Jenny Ellerbe says in her concluding section: “I wish, fervently, that all who come here will see this great city as it once was and take the time to honor the bold and creative people who built it.”

The two authors create a right-brain/left-brain approach to Poverty Point that produces a book to please all readers. It is handsome enough to sit on a coffee-table, yet also scholarly enough to answer contextual questions about the history and geography of the site. To add to its academic bona fides, the book includes a full list of references and further reading, as well as a very useful glossary at the back of the book to define terms like “pedogenic” and “atlatl” for the lay reader whose knowledge of the science behind archeology and anthropology is slight. Poverty Point: Revealing the Forgotten City well deserves its status as an LEH Book of the Year: it is interesting, informative, and beautiful to look at. And I hope that it brings readers to visit the site for themselves. As Jenny Ellerbe says in her concluding section: “I wish, fervently, that all who come here will see this great city as it once was and take the time to honor the bold and creative people who built it.”

—–

A native of London, England, Dr. Helen Clare Taylor is the O. D. Harrison, Jr. Professor of the Liberal Arts at LSU Shreveport.