Bookstand

Freedom on the Move in Louisiana

Archived notices of people escpaing slavery plot a geography of resistance

Published: December 1, 2019

Last Updated: March 2, 2020

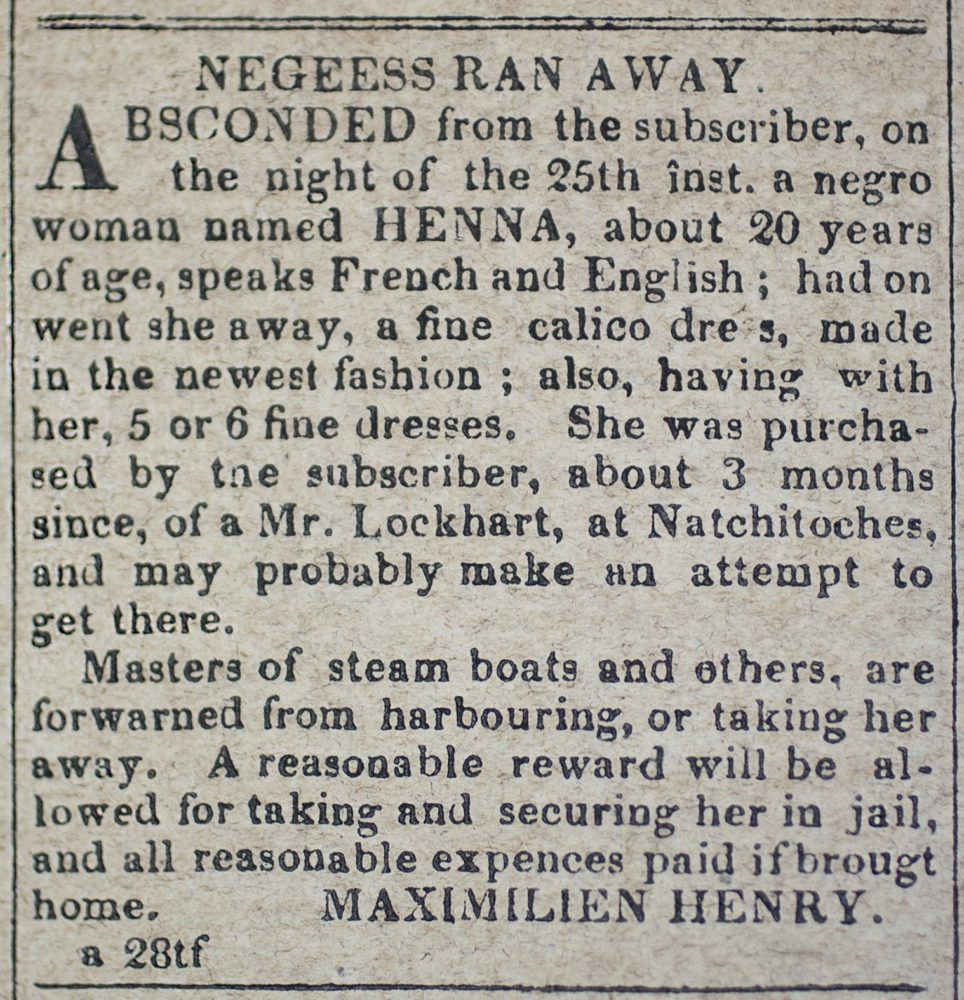

Louisiana State Gazette. Louisiana Division, City Archives, New Orleans Public Library

Ads like this one, for an enslaved woman named Henna, who ran away from her new owner in August 1826, are the subject of the searchable Freedom on the Move database.

Runaway slave ads provide a treasure trove of information about the lives of enslaved individuals. Masters supplied all manner of details about runaways for identification purposes: skin tone; eye color; hair color, texture, and length; height, weight, and build; age; physical markings and disabilities; clothing; and skills and knowledge, including languages and literacy. Ads often contained descriptions of fugitives’ perceived behavior and anticipated disguises adopted to elude detection. Familial and other relationships among enslaved people are illustrated through the ads, as well as where fugitives were born and places they lived. Although filtered through the enslavers’ perceptions, these types of details illuminate the stories of thousands of enslaved African Americans that otherwise would remain unknown.

These rich historical documents have become more accessible thanks to Freedom on the Move (FOTM), an online database that will contain forty thousand runaway slave advertisements by the end of 2019. With funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Archives, Cornell University historians and developers, in collaboration with other scholars, including Dr. Mary Niall Mitchell, Associate Professor of History at the University of New Orleans, launched FOTM in February 2019. FOTM offers a vast and growing resource to scholars, family researchers, students and teachers, and anyone else interested in learning more about the lives of enslaved Africans and African Americans. The searchable database contains digitized ads from the early 1700s to the 1860s, which the public transcribes through crowdsourcing. Over the next year, FOTM collaborators will debut an online education portal for use in classrooms and develop software for future museum kiosks. Runaway ads digitized by Louisiana State University will be added to the database, increasing the number of Louisiana-based ads accessible in one place.

Through the inclusion of multiple New Orleans newspapers, the FOTM database makes visible a geography of slave resistance across Louisiana. A man named Benjamin, for example, ran away from Bayou Boeuf in Rapides Parish and was captured in West Baton Rouge. Handerson and Gurley ran away from a sugar plantation in St. Charles Parish, making it through St. John the Baptist Parish before being caught in St. James Parish. Often ads pointed to fugitives’ likely destinations and the rationales for their decisions. Snodgrass, for instance, advertised in New Orleans in part because Rachel had previously lived there. The large port was a common destination because it allowed runaways like Green and Rachel to blend in and earn a living, while offering better access to transportation to free states or other countries via the river and the gulf. Not everyone sought refuge in New Orleans, however. John escaped his new master in the city after being purchased from John and Alfred Waddell in Natchitoches. He likely headed towards Catahoula or Concordia Parish, where his wife was enslaved.

Fugitive slave ads functioned as part of a system of control and surveillance of people of African descent. While their specificity increased the chances of capture, the ads also made any black person on the move a suspected runaway who, if lacking the required documentation, could be detained. Law enforcement officials placed ads to alert enslavers of captured fugitives. In 1828, the warden in Baton Rouge advertised a man in his jail named Johnson, who had been “shot in the legs by those who stopped him.” Ads like this suggest the incredible risks the enslaved took when they ran away.

The Louisiana ads collected in FOTM also make abundantly clear the violence that undergirded the system of slavery. Neptune, captured in St. John the Baptist Parish, had “several scars on the breast, one on the forehead, and one on the left eyebrow, as well as on the left arm, and several on the back occasioned by the whip.” John, a fugitive from Iberville Parish, also had “his back . . . considerably marked by the whip, the marks of long standing.” In addition to scars, ads reported fugitives with burns, thumbs that had been removed, missing toes, and legs bitten by dogs. Violence and running away formed a vicious circle. Captured fugitives often suffered corporeal punishments, while enslaved people sometimes ran away after experiencing what they judged to be excessively harsh treatment. An 1844 ad described Rachel, who “had on an iron collar with three prongs, with a small bell attached to each prong.” Enslavers used such devices to punish serial fugitives and discourage additional escapes. Whether because of the collar or despite it, Rachel made clear her desire for freedom when she ran away wearing it.

Reading through thousands of fugitive slave advertisements in FOTM can be overwhelming in their sheer number, evidence of brutality, and scenes of heartbreaking desperation. Yet in vividly illustrating the lived realities of slavery, the stories that emerge from the database demonstrate the incongruity of treating people as property, and they serve as poignant reminders of the significant risks that people will take to seek a better life. The FOTM ads can tell us much about individual enslaved African Americans and, in turn, help us better understand the race-based system of slavery in America—the legacies of which we continue to contend with as a nation today.

Elizabeth C. Neidenbach earned her PhD in American Studies from the College of William and Mary. She has worked for the National Park Service in Virginia and New Orleans. Currently, she is the Visitor Services Trainer at The Historic New Orleans Collection. Elizabeth is revising her book manuscript, “The Life and Legacy of Marie Couvent: Social Networks, Property Ownership, and the Making of a Free People of Color Community in New Orleans.”