Indigenous Slavery

Indigenous people were enslaved alongside enslaved African people as domestic and agricultural laborers, guides, interpreters, hunters, sexual companions, and wives in colonial Louisiana.

University of South Florida

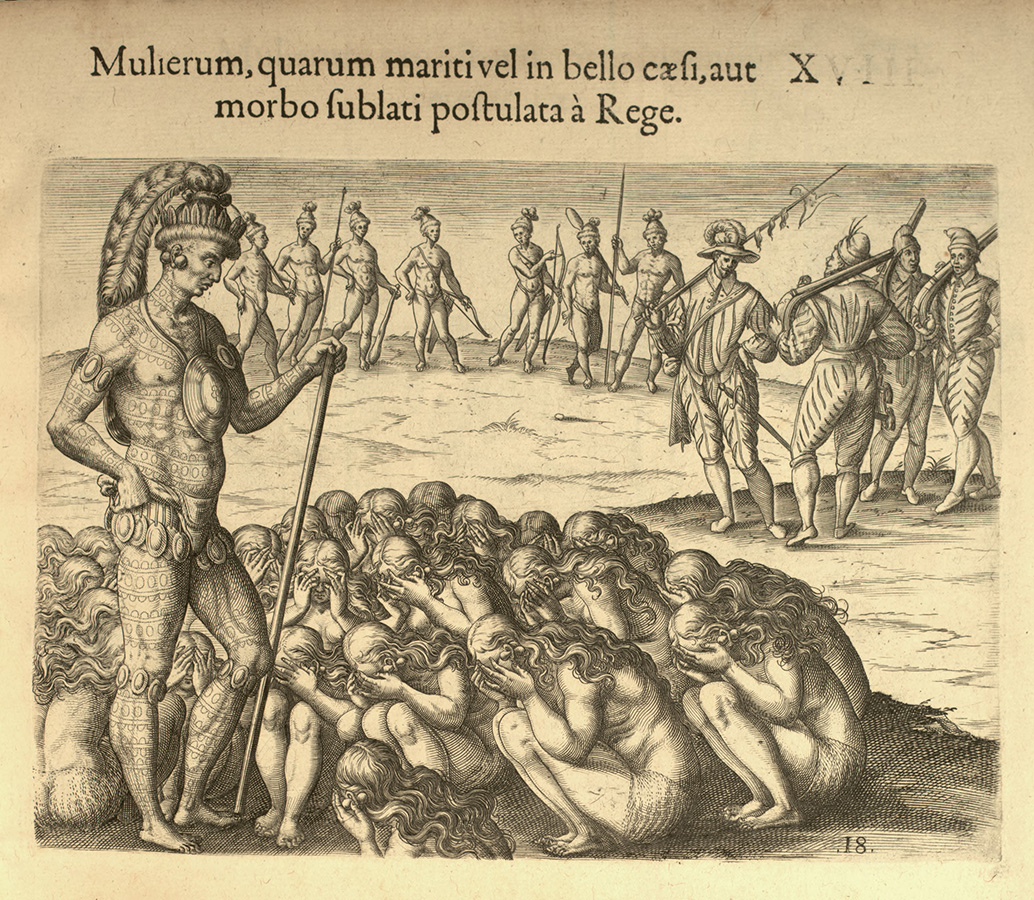

An engraving depicting a chief applied to by women whose husbands have died in war or by disease, 1591. Engraved by Theodor de Bry based on a painting by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues.

Enslaved Indigenous people were essential to the commercial and diplomatic survival and development of colonial Louisiana—specifically Lower Louisiana, or Basse-Louisiane, which includes the modern-day states of Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama—from 1699 to 1803. Although officially banned by the French and Spanish and with numbers never registering more than a few hundred, enslaved Indigenous people and the system that produced them formed an integral component of Indigenous-European relations throughout the life of the colony. Indigenous people were exploited alongside enslaved African peoples as domestic and agricultural laborers, guides, interpreters, hunters, sexual companions, and wives.

Precedents for enslaving Indigenous peoples in Lower Louisiana existed in Upper Louisiana, or Haute-Louisiane (which includes much of the modern-day midwestern United States), and Canada. The exigencies of local conditions throughout colonial Louisiana often demanded that Europeans work within preexisting Indigenous captive-taking traditions. This meant Indigenous peoples often came into European possession as war captives from allied and hostile Indigenous nations both within and from outside the colony. French and Spanish methods for acquiring captives contrasted sharply with those employed by the English Atlantic colonies, which were active in the Indigenous slave trade from the mid-seventeenth century until the Yamasee War (1715–1717) compelled their gradual disassociation from the practice. Nearly two-thirds of enslaved Indigenous people that were traded or given to the French and Spanish were women and children. New social identities were created when sexual unions between European men and Indigenous women, or métissage, produced children. These offspring could remain enslaved or be incorporated into French and Spanish society.

Indigenous slavery is understood to encompass the forcible capture and subsequent subjugation and exchange of Indigenous peoples without their consent both before and after a sustained and significant European colonial presence was established on the North American continent by the early seventeenth century. Captives both before and after the arrival of Europeans could anticipate a spectrum of experiences that might also include adoption into the Indigenous captor’s clan—a unilineal kinship group where members saw themselves as blood relatives. Different from enslavement, adoption brought the consequent benefits and rights of kinship to the captive while enhancing the captor’s clan by replacing a member that had died either in battle or from disease. Although captive taking, slavery, and other forms of physical coercion existed in Indigenous societies prior to contact, European market demand for labor and periodic desires for retribution against enemies (Indigenous and European alike), encouraged the hyper-expansion of warlike practices among Indigenous peoples in the Americas. The resultant spiral of violence and upheaval between and among dozens of Indigenous societies spread across much of eastern North America from 1650 to 1730, creating vast regions of sociopolitical instability and dislocation in what anthropologist Robbie Ethridge has described as the “Mississippian shatter zone.” This “shatter zone” had geographic limits, and French Louisiana formed its western edge. Conservative estimates reckon that hundreds of Indigenous towns were destroyed and tens of thousands of Indigenous people from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast and from the Atlantic Coast to the Mississippi River lost their lives and freedom during this period of intense enslavement, disease, and warfare.

While European colonization was a set of circumstances and economic forces that could often be destructive to traditional Indigenous lifeways, it could also be culturally restorative and produce political innovations. The Indigenous political arrangements that emerged in response to the violence of the Indigenous slave trade were more resilient and shaped European North America for much of the eighteenth century. Often formed by the joining of people from the splintered remains of larger, more complex communities, these coalescent societies simultaneously drew upon and deviated from precontact political and social institutions in ways that helped them transition into potent adversaries to one another and to European colonizers. The Creek and Caddo confederacies, Choctaws, Cherokees, and Chickasaws represent examples of coalescent societies that selectively integrated elements from their Mississippian chiefdom past that still exist today.

Precontact Indigenous Slavery

Slavery in its many forms existed among the Mississippian chiefdoms and long before Europeans arrived in the North American Southeast and lower Mississippi valley. Although enslaved people in these precontact societies could be obtained through trade or given as gifts for alliance building, war and raiding were the most conventional means for their procurement. Archaeological findings demonstrate the centrality of warfare to the Mississippian worldview and cosmos. Violent iconography, visible trauma on human remains, and geophysical anomalies under the soil exhibiting the presence of once-fortified towns speak to the norm of inter-group conflict between these pre-state societies. Slaughter during war was often indiscriminate, but when captives were taken, they were most often young women of reproductive age. Captors prized women over men because they were easier to rehabilitate, less likely to rebel, and could provide menial labor, adoption into family units, marriage, sexual companionship, and in some instances, sacrifices in the form of retainer burials. Captured men, who were usually warriors, faced torture and execution as part of an elaborate grief ritual for family members killed in combat. Many of these customs continued after the appearance of Europeans, but the introduction of commercial slavery during the mid-seventeenth century fundamentally changed the approach to captive taking.

The Commercial Indigenous Slave Trade and the Rise of Militaristic Slaving Societies

European exploration and colonization of North America during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries radically altered Indigenous societies through the introduction of Eurasian diseases such as influenza and smallpox; trade in iron tools, linens, alcohol, and firearms; and the proliferation of mutually destructive conflict on an unprecedented scale. From 1650 to 1730, much of this transformation in the North American southeast was subsumed in the widespread capture and enslavement of Indigenous peoples in what scholars have termed the commercial Indigenous slave trade. The Dutch, French, and Spanish participated in commercial slavery to varying degrees, but it was the English from the colonies of Virginia and Carolina (and North and South Carolina after 1712) that came to dominate this trade. While the scope and scale of the trade varied in effect, region, time, and purpose, it remained violent, destabilizing, market driven, paradoxically destructive and regenerative for many Indigenous communities, and crucial to fueling the economic growth of the Atlantic World. It also helped finance the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade throughout the Western Hemisphere. As a system and a condition, the commercial Indigenous slave trade describes the physical and legal control of Indigenous people by European colonizers for the purposes of extracting labor, exerting authority over Indigenous land and communities, weakening imperial colonizer rivals, and furthering regional trade schemes.

Indigenous Americans were participants in and victims of the commercial Indigenous slave trade. Through the capture, enslavement, and overland transport of other Indigenous peoples, whom they viewed as outsiders or regional rivals, Indigenous enslavers merged traditional rationales for war into mercenary interests, forging powerful commercial and diplomatic ties with European colonizers settled on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Growing demand for laborers in the profitable Caribbean sugar island colonies encouraged the expansion of this trade and led to the emergence of Indigenous societies specifically oriented towards captive taking or what Robbie Etheridge has described as “militaristic slaving societies.”

Indigenous Slavery in French Louisiana (1699–1763)

When the French arrived on the Gulf Coast in 1699, they encountered a region enmeshed in the violence of the commercial Indigenous slave trade. Some Indigenous refugees migrated from their homelands to resettle near the French for the protection they offered through a trade in guns.

Desperate for laborers to clear land for cultivation, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville, hoped to replicate the English model of commercial slavery and petitioned officials in France to exchange Indigenous captives for enslaved African people in the Caribbean. However, France feared the destabilizing effects of the trade would ultimately imperil the small colony’s alliance networks and banned Indigenous slavery in 1710. Typifying the local autonomy that came to characterize life in the colony, the prohibition was ignored. Louisiana not only accepted Indigenous captives as an important feature in maintaining friendship with Indigenous allies but also in exercising vengeance against Indigenous enemies. The Indigenous slave trade extended Louisiana’s commercial networks beyond its borders with frontier settlements like Natchitoches quickly becoming way stations for Osage, Pawnee, and Lipan Apache captives taken from distant corners of the Great Plains.

The 1706 killing of priest Jean-François Buisson de Saint-Cosme and three companions as they encamped on the banks of the Mississippi River by a band of Chitimachas brought Louisiana its first significant enslaved population. Bienville understood that retaliation for the attack was necessary to preserve honor with Indigenous allies and inaugurated a twelve-year campaign against the Chitimachas that brought scores of women and children to Mobile and New Orleans. Retaliating against aggressive land seizures and other abuses suffered from French tobacco plantation owners brought a second wave of enslaved captives to New Orleans after the Natchez annihilated Fort Rosalie on November 29, 1729. While many Natchez found sanctuary among the Chickasaws and Creeks, hundreds of others were killed or sold into Caribbean slavery.

Enslaved African people outnumbered enslaved Indigenous peoples in the colony after 1719. From 1717–1721, the Company of the Indies brought two thousand West African people aboard eight ships to New Orleans. A 1726 census registered 1,540 enslaved Africans and 229 enslaved Indigenous people. By 1731 the enslaved African population had grown to more than four thousand, while the enslaved Indigenous population still hovered around a few hundred. The importation of additional enslaved African people ceased, however, in the aftermath of the Third Natchez War as administrators increasingly feared that the influx of enslaved African people and growth of the plantation economy would unite Indigenous and African people and spark similar outbreaks of violence against French landowners.

With so few French women available in the colony, liaisons between French men and the only viable alternatives became a matter of course. Although diverse customs pervaded Louisiana, when French and Indigenous marriage, or métissage, occurred, it was most often between a French man and an enslaved Indigenous woman. Indigenous wives provided their French husbands sex, labor, and children. Opinion on métissage stirred debate between civic and religious officials, with the matter eventually settling into a legal gray area. Children from these marriages could remain enslaved or be freed and incorporated into surrounding communities, where they intermarried with white or Afro-Creole people.

Indigenous Slavery in Spanish Louisiana (1763–1802)

In 1769 Governor Alejandro O’Reilly issued a series of “Ordinances and Instructions,” which banned Indigenous slavery. The new regulations did little to curb the trade, especially in frontier outposts such as Natchitoches, where the traffic in human captives was controlled by a cartel of Creole families and where alliances with the Caddos and Witchitas depended on the goods the trade provided. The reissue of the ban by Governor Esteban Rodríguez Miró in 1787 invited legal petitions for freedom from enslaved persons with claims of Indigenous ancestry. At least thirteen such cases were heard at the governor’s court in New Orleans from 1790 to 1794, resulting in the emancipation of several plaintiffs. However, under pressure from enslavers, Spanish Governor Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet issued a moratorium on challenges to Indigenous slavery. Avoiding future legal contests, enslavers began identifying enslaved people as either “Black” or “mulatto.” Commodifying Indigenous people in Louisiana was phased out as a practice after the Louisiana Purchase. The coalescence of smaller nations into larger ones, migration in the face of an advancing Anglo-American settler state, and the accompanying colonial Black-white racial binary combined to gradually dissolve Indigenous slavery. However, its legacies abound in the genealogies of individuals and descendant communities, including the Choctaw-Apache Tribe of Ebarb, Louisiana.