Spring 2023

“I’m Not Playing”

An excerpt from Moving the Chains: The Civil Rights Protest That Saved the Saints and Transformed New Orleans

Published: February 28, 2023

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

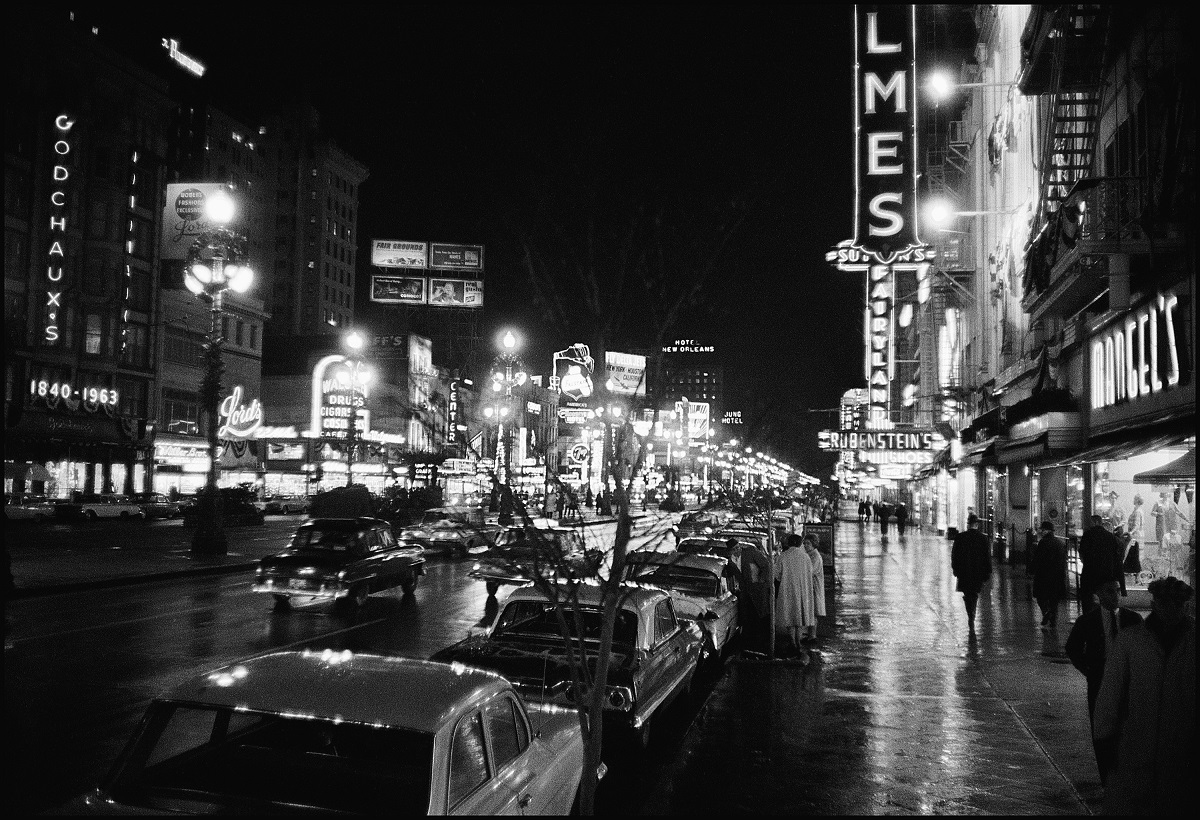

The Photojournalism of Del Hall, LSU Press, 2015.

Canal Street, mid-1960s.

. . . . Half a dozen taxis sat outside the Roosevelt, but as Clem Daniels, Dick Westmoreland, Ernie Ladd, and Dave Grayson approached, drivers walked away. When a player tried to get in one cab, the driver announced he could only carry Black passengers who were with a “white associate.”

The group walked down the sidewalk away from the hotel to flag someone not under peer surveillance. After several more vacant taxis passed, Clem Daniels lost his patience and stepped in front of the next oncoming cabbie, who stopped short of the halfback and agreed to haul them the short distance to the French Quarter. There, the group splintered and milled about, looking through windows and gauging music. Westmoreland, Ladd, and Grayson liked a tune coming from one little joint and decided to check it out. They were stopped instantly by a bouncer who stated that no African Americans were allowed inside. Turning away, Westmoreland wondered why a club opposed to Black presence was playing James Brown.

Daniels strolled past a different venue, one with three rooms and a band in each. As he stepped inside the first space, the music stopped immediately, and walking into the other two got the same result. In the third, however, when the band broke, he sat down at the bar and had one drink, in nearly complete silence. Likewise, nearby, Earl Faison felt like a magician: when he entered the crowded foyer of the Playboy Club, he made everyone else disappear.

Westmoreland was most shocked when walking around with Ernie Ladd, who was six-foot-nine and 320 pounds. Westmoreland could not believe how many scrawny white guys dared to speak slurs right to the players’ faces. He also worried about Ladd’s temper and lobbied for an early curfew. But the party tried one last club. This time, the bouncer pulled out a gun and barked, “You n——s are not coming in here.” Everyone jumped back but Ladd, who took another step forward. The doorman put the gun to Ladd’s nose and announced, “I will pull the trigger!”

LSU Press.

“Hey man, we better start thinking about getting out of here,” Westmoreland said, looking around. “We kind of got a mob out here now.” Ladd did not flinch. He stood his ground a moment more and then calmly stepped back to join the other All-Stars’ tactical retreat. Again, however, cabbies claimed they could be arrested for driving a car of only African Americans. So the players got directions and started back to the Roosevelt on foot.

The walk did nothing to temper their ire. “I don’t need to take this crap,” Ladd asserted.

“I’m taking my Black a’ home,” Westmoreland concurred, “I’m not playing.”

. . . . When the civil rights movement swept Louisiana, little was more out of sync with the Big Easy’s branding than change. Even as race riots and violence blacklisted the town, progress was kept behind closed doors in the interest of public approval, at least until the action of fifty-eight Black and white AFL All-Stars made it clear that inch-wise, piecemeal, behind-the-scenes advancement did not befit a big league city. As a result, for the first time New Orleanians had a popular cause and a common goal to rally behind en masse and out in the open. Suddenly, conservatism was obstructionism and a socially perilous stance.

Moreover, locals found a way to be, as Mayor Vic Schiro proposed, both the traditional city and the city of change. A locale long renowned for enchanting stagnation found itself advertising its shiny new modernity, and civic identity was in flux. The pro club was immediately folded into the city’s defining features of Mardi Gras, jazz, and red beans and rice, and locals’ absolute fanaticism over the franchise was a common denominator breaching barriers of race, generation, or politics. Perhaps most powerfully, since an enemy’s enemy is a friend, the existence of common (external) rivals gave a new complexion to the dichotomy of “us versus them.”

EXCERPT FROM:

Moving the Chains: The Civil Rights Protest That Saved the Saints and Transformed New Orleans

by Erin Grayson Sapp

$29.95; 312 pp.

Louisiana State University Press

October 2022