The Big Cat and the Bigger Dog

Ernie Ladd, the Junkyard Dog, and the intersection of sports, race, and culture in New Orleans

Published: November 29, 2020

Last Updated: February 28, 2021

Wikimedia Commons

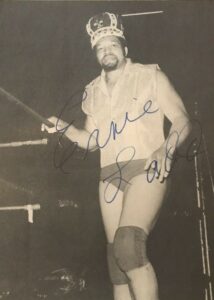

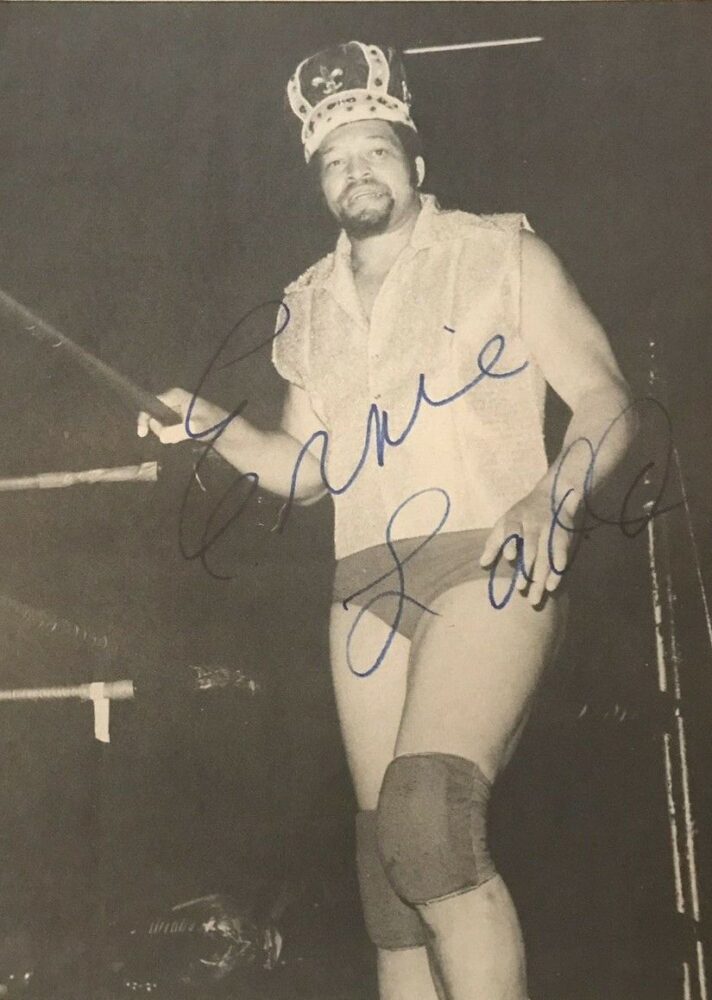

A signed 1976 publicity shot of Ernie Ladd.

As an example we can look to professional wrestling in Louisiana, which in the 1960s–1980s reflected the tumultuous social and political changes of the times. Two iconic African American wrestlers, Sylvester Ritter (The Junkyard Dog) and Ernie “Big Cat” Ladd, represented this intersection of professional wrestling, football, civil rights, and the ever-evolving and often controversial status of Black Americans in the South.

Before Vince McMahon finalized his WWE professional wrestling empire, transforming “rasslin’” to “Sports Entertainment,” the business resembled an economic cartel controlled by a single, governing entity, the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA). Starting in 1948, promoters owned autonomous territories operating under the auspices of the NWA, and they worked together to exchange talent, ideas, and ideally, avoid taking over each other’s businesses by crossing territorial lines. By the 1970s, television accelerated the popularity of professional wrestling. Promoters and owners of the territories contracted with hundreds of local TV stations to air weekly shows designed to draw an ever-increasing fanbase to arenas.

A native of Rayne, Louisiana, born in 1938, Ernie Ladd was built for football and wrestling, standing at six-foot-nine and tipping the scales at 325 pounds. After graduating from Grambling State, Ladd played defensive end for the Kansas City Chiefs and the San Diego Chargers from 1961 to 1968. He began wrestling while in Kansas City, ultimately deciding to dedicate his athletic career to it because it paid well; Ladd noted, “I quit football at twenty-eight and still had several good years left. That first year wrestling, I made $98,000, and after that never made less than a hundred grand a year. That was big money back in the ’60s.” Trained by another African American superstar, Bobo Brazil, Ladd became a main event attraction in several territories, including Mid-South and the WWE.

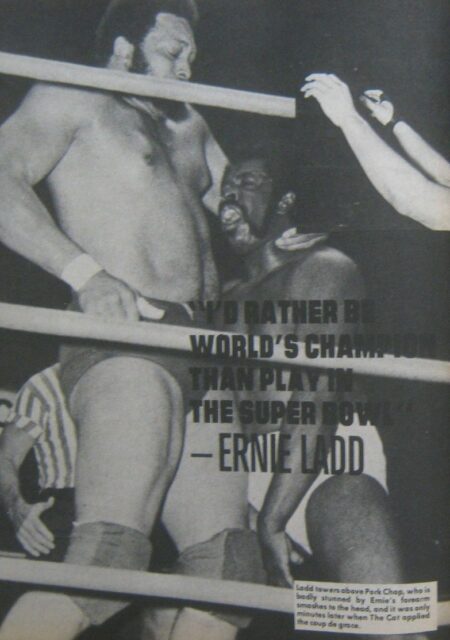

Ladd appears in the process of administering defeat to Pork Chop in this page from the 1975 Wrestling Annual. Wikimedia Commons

Ladd found himself in the middle of a lesser-known but defining event in the history of civil rights in New Orleans, mirroring many places in the South and the rest of the nation. By 1965, the fledgling American Football League football league had become a legitimate competitor to the National Football League. The AFL All-Star Game was scheduled for January 15, 1965, but several players began arriving in New Orleans days before to enjoy the local culture. Upon arrival, Black players encountered everything from angry stares to racist comments. A group of Black players decided to take in the sights and sounds of the French Quarter. They were drawn to a Bourbon Street bar playing James Brown and tried to enter; using racist language, the doorman told them they were not allowed in the bar. Ernie Ladd then told the doorman that he was going to rip the doors off the hinges and enter the establishment; the doorman brandished a gun and convinced the group that moving on was the wiser choice. The incident resulted in a players’ boycott of the AFL All-Star Game, led by Ladd.

The boycott led league officials to move the game to Houston, and it had implications for the city of New Orleans and their new NFL team, the Saints. David Dixon, the longtime businessman and urban booster, convinced the NFL that New Orleans deserved an NFL team. Even after the league approved the measure, he begged the Black players to not boycott the AFL All-Star Game, knowing it might damage the possibility of the NFL awarding a franchise to the city. On All-Saints Day in 1966, the NFL awarded New Orleans a team, but the city continued to recognize the need to improve its image as a tourist destination. The incident also allowed civil rights leaders to further leverage tourism as a way for local businesses to begin complying with recent federal laws protecting civil rights. In 1969, the city adopted a comprehensive public ordinance strengthening federal statutes to protect African American access to the city’s public places.

The Junk Yard Dog (JYD), born Sylvester Ritter, December 13, 1952, in Wadesboro, North Carolina, became the most popular wrestler in the Mid-South territory. JYD also was integral to the establishment of the now-universal “Who Dat” chant popular with New Orleans Saints fans. The Cincinnati Bengals’s “Who Dey” cheer was created during their 1981 winning season, which culminated in an appearance in Super Bowl XVI. Although the “Who Dey” cheer preceded the “Who Dat” chant, the latter was not a cheap rip-off. By 1982, transcending race and class, JYD was the most popular athlete in the city of New Orleans according to a Times Picayune poll; JYD bested icons “Pistol” Pete Maravich and Archie Manning. Evidence suggests that fans used the “Who Dat” chant to cheer on JYD at wrestling events in the city; the cheer also emerged at local high school football games. By 1983, when the Saints began to have some success on the field, the “Who Dat” chant became ingrained in the team’s culture and tradition, even inspiring a popular song written by Aaron Neville (backed by the Singing Saints).

Ernie Ladd and JYD reflect the ever-enduring intersection of sports, culture, and social issues. Dismissing or separating athletes and sporting culture from larger society and the context in which they reside is ahistorical and anachronistic.

Chris Stacey is an associate professor of history at LSU Alexandria.