Innovative New Interpretations of Centuries-Old Music

The lyrical legacy of Caesar Vincent

Published: August 30, 2019

Last Updated: February 3, 2021

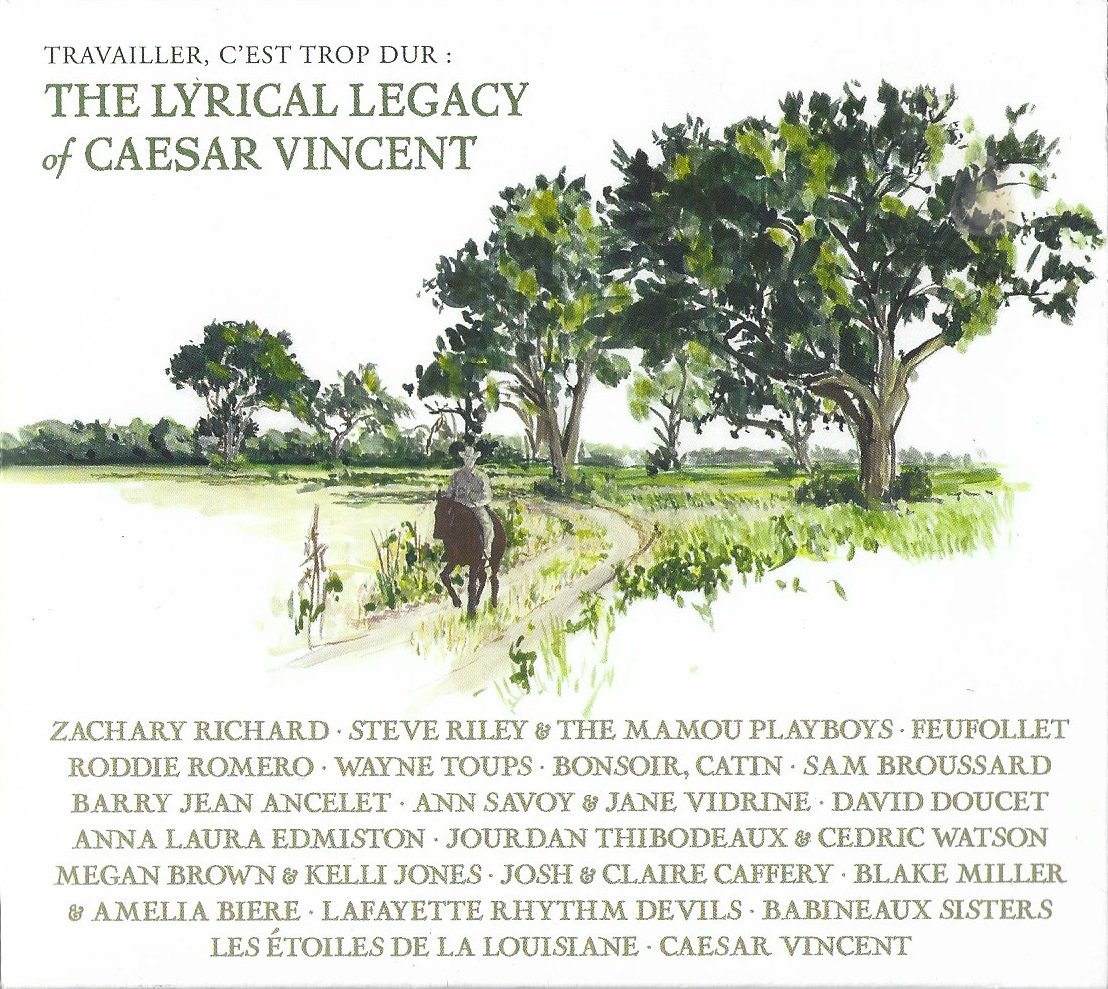

In 2018, Festivals Acadiens et Créoles released a Caesar Vincent tribute album, Travailler, c’est trop dur.

When singing in French, however, Caesar Vincent burst forth with an ebullient, full-throated style that conveyed considerable passion and great dramatic flair. He propelled such raucous panache with assertive timing, a pleasing adherence to true pitch, and a sophisticated sense of melody and melodic resolution, even though he had no formal musical training. The self-taught nature of Vincent’s singing was most obvious in his mastery of successive ancient verses that lacked uniform length, thus requiring precise rhythmic dexterity to avoid dropping the beat.

Caesar Vincent never worked as a full-time musician. He made his living as a subsistence farmer and day laborer in rural Vermilion Parish. On occasion Vincent was hired to perform at local events. But people in Vincent’s community heard him far beyond such sporadic gatherings, because Vincent sang with great frequency, wherever and whenever the spirit moved him, be it at family gatherings, inside the neighborhood grocery store, or while walking along rural roads. It was said that Vincent’s voice resonated far across the countryside, long before he came into sight.

Some people, both in Vincent’s family and his local community, did not understand or appreciate the vast cultural significance of his music. Such indifference accelerated after the second World War, when Cajun music in general suffered a lull in popularity, and ever-increasing assimilation eroded the traditions and way of life that Vincent represented. Accordingly, Vincent was frequently dismissed as eccentric, annoying, hopelessly antiquated, and even, at times, embarrassing. As a result, nobody in Vincent’s family ever learned his songs. One descendant has stated that the forty-four selections recorded by Blanchet and Oster represent a mere fraction of Vincent’s complete repertoire. Had Vincent lived into the mid-1970s he would likely have been embraced by the Cajun and Creole renaissance that brought unprecedented attention and performance opportunities to such ballad singers as Inez Catalon, Lula Landry, and Alma Barthélémy, and inspired such young apprentices as Marce Lacouture. Had such recognition occurred, the full range of Vincent’s musical knowledge might well have been preserved.

“The mosquitos ate up my darling—they left only the big toes to make corks to stop up my half-bottles.”

Not long after his death, one of Vincent’s songs, “Travailler, c’est trop dur,” garnered far-reaching acclaim around the French-speaking world. After appearing on an esoteric anthology of historic Cajun music, it was re-recorded by the French folk-revival band Grandmère Funibus Folk in 1974. Their rendition led in turn to versions by such first-generation Cajun-resurgence musicians as Zachary Richard and the band BeauSoleil, which subsequently influenced stylistically diverse cover versions by the Parisian pop-rock singer Julien Clerc and the African reggae star Alpha Blondy. Now, decades later, “Travailler, c’est trop dur” has attained newfound prominence as the title track for a two-CD tribute album subtitled The Lyrical Legacy of Caesar Vincent (Swallow Records/Festivals Acadiens et Créoles, Inc.) The project was co-produced by Barry Jean Ancelet; Patrick Mould, a co-producer of the annual Festivals Acadiens et Créoles; and Chris Stafford, the multi-instrumentalist renaissance man from the Lafayette-based Cajun band Feufollet.

Travailler, C’est Trop Dur assembles some of contemporary Cajun music’s leading interpreters. They perform Vincent’s songs with faithful adherence to his rich lyrics and complex melodies. Some accompaniment reprises the classic accordion-and-fiddle sound that Vincent heard in Vermilion Parish. But other songs venture very far afield —touching on jazz, western swing, ambient electronic music, rock, and more —underscoring the wave of creative experimentation that is currently energizing Cajun music. Such evolution and imaginative reinvention separate a true living tradition from one that is locked in an airless display case. In this sense Travailler, C’est Trop Dur recalls the 2015 anthology I Wanna Sing Right: Rediscovering Lomax in the Evangeline Country (Valcour), produced by Joel Savoy and Joshua Caffery. That project faithfully preserved the lyrics to Library of Congress field recordings from 1934 while presenting them with novel new arrangements. Many musicians who recorded on the Lomax project are likewise featured on this tribute to Caesar Vincent. (Experimentation with the Lomax material has been ongoing since 1987, when thirty-eight songs from this vast collection were released on vinyl by Swallow Records of Ville Platte, Louisiana.)

While space limitations preclude discussion of all twenty songs here—Ancelet needed forty manuscript pages to write the accompanying booklet of liner notes—this album is consistently strong, soulful, and fully realized. It is also quite effectively sequenced, especially given its eclectic sonic range; such decisions regarding the best possible order of songs can be quite challenging for producers. Keen musical intelligence and deep attention to detail suffuse the album throughout, and such intricacy is implemented in a seamless, organic manner.

“With her Mary Jane and cotton from the north and two pieces of ten cents a yard . . . if you don’t love me, you’re committing a mortal sin.”

The opening track, “Là bas oh dans ces bois,” begins with Vincent’s original 1950s vocal superimposed over a rhythmic pattern played by Sam Broussard on the head of a banjo. As Vincent’s vocal continues, Broussard adds resonant guitar chords, effectively separated by suspenseful silence, followed by more richly textured guitar work and increasingly louder, reverberating percussion. These components combine to build harmonic tension within the broader context of an ever-expanding modernist soundscape. Broussard’s approach here recalls that heard on Broken Promised Land (Swallow), his Grammy-nominated collaboration with Ancelet from 2016.

The next song, “Avec sa Mary Jane et du coton du nord,” is a Vincent original, in which Mary Jane refers to a style of women’s shoes with a strap across the instep. The lyrics focus on a young man who seeks a young woman’s hand in marriage, albeit in a distinctly non-linear fashion: “With her Mary Jane and cotton from the north and two pieces of ten cents a yard . . . if you don’t love me, you’re committing a mortal sin.” (Vincent could also veer into full-on grassroots surrealism at times, as heard on The Lafayette Rhythm Devils’ rendition of “La valse du vieux Ropopio”: “The mosquitos ate up my darling—they left only the big toes to make corks to stop up my half-bottles.”) Vincent sang about shoes, cotton, and unrequited love with emphatic rhythmic accents that are deftly reproduced here by a hard-driving band, led by guitarist Roddie Romero. They accompany Ancelet, Romero, Wayne Toups, and Zachary Richard on a lead vocal with rough-edged four-part harmony. Zachary Richard is also featured as a solo vocalist on the exquisitely understated “La fille aux oranges,” singing over a layered bed of overdubbed guitar parts that is simultaneously twangy and ethereal. Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys raise the dynamic level on the urgent, upbeat “Mon aimable catin” and also contribute a classic swamp-pop groove on “La belle en danger de mourir.”

On “Les anneaux de Marianson,” Anna Laura Edmiston’s lush delivery belies a very grim tale of deceit, betrayal, and murder. Ann Savoy and Jane Vidrine create a similarly stately mood, somewhat reminiscent of Gregorian chants, on the medieval “La belle et le capitaine,” a story with a happily redemptive ending. The multi-talented women of the band Bonsoir, Catin—whose 2017 album L’Aurore (Valcour) stands as one of recent years’ most important Cajun-music creations —bring a rocking feel to “Il y a une fille à marier,” featuring Kristi Guillory’s resounding lead vocal. Jourdan Thibodeaux and Cedric Watson revel in the rollicking sound of traditional Creole juré music on “Tobie Lapierre,” while David Doucet’s stark, brooding take on “Amour trompeur, grand amuseur de fille” showcases the unique style of acoustic-guitar picking that he introduced to Cajun music.

The album ends, appropriately, with a field recording of Caesar Vincent singing “Travailler, c’est trop dur” with no added instrumentation. Those who wish to hear more of his music can visit the website ReverbNation, where a search of the misspelled name Ceasar Vincent will pull up twenty-six of his 1950s songs. In addition, at some point in the future, the Center for Louisiana Studies plans to post all of Vincent’s recordings on its website.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based writer, folklorist, producer, and the former drummer for the Grammy-nominated Cajun/Western swing band The Hackberry Ramblers. In May 2018, the LEH honored Sandmel with an award for his Lifetime Contributions to the Humanities.

Sound Advice is funded in part by a grant from the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation.