Into Thin Air

The loss of Shreveport’s C. C. Antoine House highlights a need to protect vulnerable historical sites

Published: August 31, 2023

Last Updated: November 30, 2023

Photo by Henrietta Wildsmith, USA Today Network

The aftermath of the fire.

Lee took the news hard. Since 2010 he and his sister, Tammi T. Wright, have organized and promoted a series of annual festivals and events honoring Antoine in Shreveport. These events include the C. C. Antoine Black History Festival held each February, the C. C. Antoine Memorial Celebration in May, and an annual birthday observance in September.

“I was devastated,” Lee said. “But then, I was already pissed off because the house had been left in such a state of disrepair for so long. The fire completed the death of this wonderful structure, but the fire wasn’t the catalyst for its death. The catalyst was neglect.”

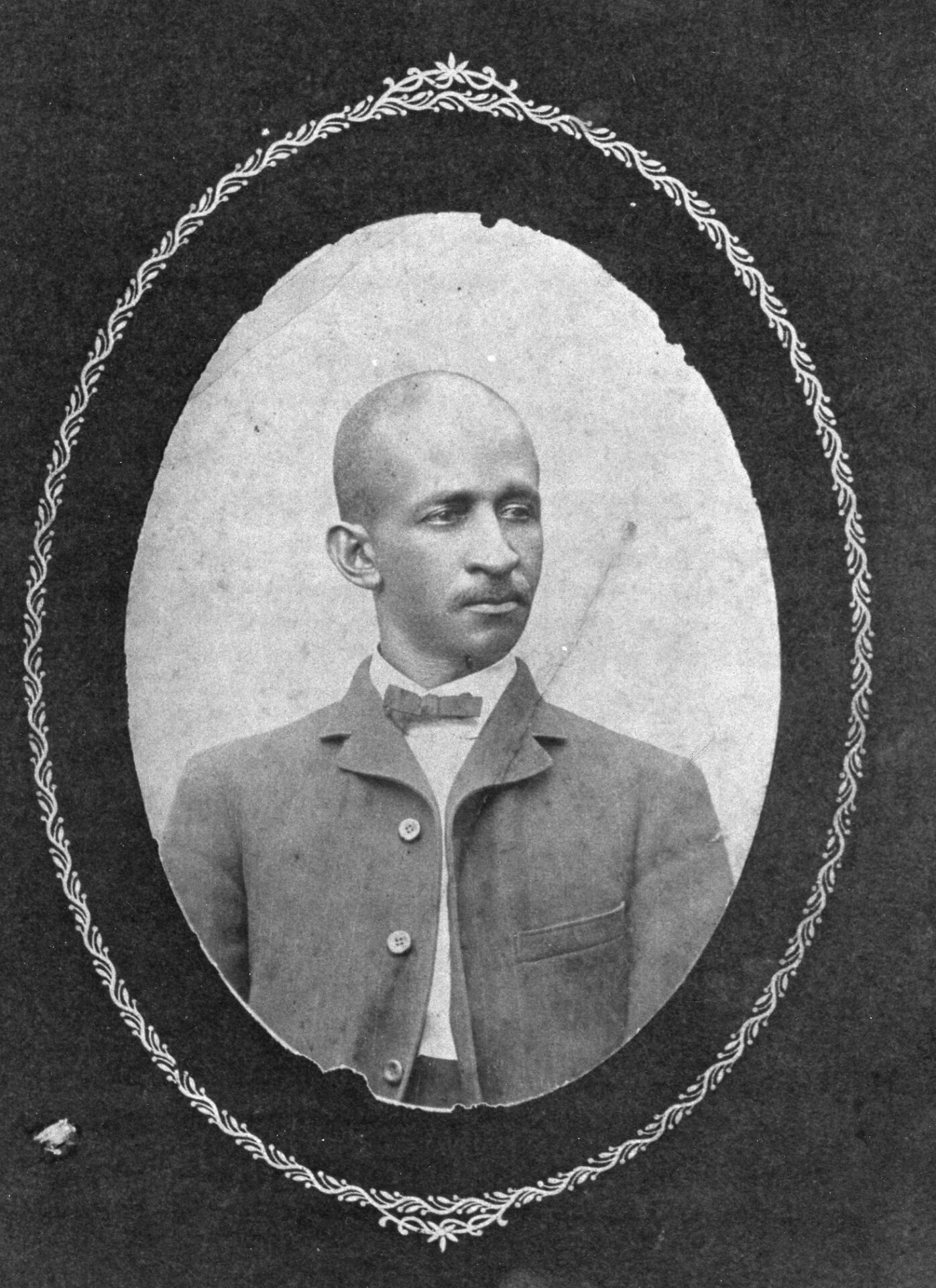

C. C. Antoine ca. 1873. LSU Shreveport.

The house in 2019. Wikimedia Commons user Renelibrary.

After receiving word of the fire, Lee got dressed and drove to Perrin Street. He learned from firefighters and media on the scene that arson was suspected, and that a similar fire had engulfed the house next door less than two months earlier. As he stood in the street watching smoke rise from the rubble, Lee said, anger washed over him.

“The disrespect for our ancestors is so overwhelming at times,” he said. “The lack of care for Black cemeteries, historic sites . . . C. C. Antoine is world history, and to see that no respect was placed on his home was just disheartening. We can’t continue allowing our history to evaporate into thin air like that.”

Rudy Glass is president of the Lakeside–Allendale Neighborhood Association and a lifelong resident of the neighborhood. Glass said that, while he appreciates the efforts of volunteers like Lee who stepped up to look after the C. C. Antoine House, volunteers shouldn’t be expected to maintain and protect a resource as fragile as an endangered historical site. If a place is considered important enough to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, he wondered, shouldn’t someone be keeping an eye on it?

“There needs to be some legislation done to protect these kinds of buildings,” Glass said. “A lot of the time, it’s just an individual who is trying to save places like this, and that individual may not have any resources. At the very least, the city could have kept the property up, kept the grass cut, you know? I believe that would have made a difference.”

Gary Joiner is the Mary Anne and Leonard Selber Professor of History at Louisiana State University in Shreveport and chairman of the Shreveport Historic Preservation Commission. He agrees with Glass. “You have to have protection for these properties,” Joiner said. “Everyone from the guy who mows for the city up to the mayor needs to understand the importance of places like this. If grants and loans are needed—because preservation is not cheap—then cities should be pursuing those grants and loans.”

What a historic place has to offer visitors, after all, is historicity. To walk the same floors or look out the same windows that a great figure from history once did can be a powerful and inspiring experience.

Joiner, like Lee, acted as an unofficial steward for the C. C. Antoine House at various times throughout the years. Along with his late friend and fellow historian Eric J. Brock, Joiner researched and wrote the successful application for the C. C. Antoine House to be listed on the National Register. Joiner was also one of a small group of volunteers who spent two years locating Antoine’s grave in the cemetery of Bethlehem Missionary Baptist Church in Shreveport. After locating the grave with the assistance of congregation members, Joiner spent an additional year working with then Shreveport City Councilman Cedric Glover to secure an appropriate military headstone for the statesman’s grave. Antoine’s Union Army headstone was dedicated in 1999, seventy-eight years after his death.

Some of those who worked to preserve the C. C. Antoine House believe that a replica of the house should be constructed at the park as planned. Others seem reluctant to embrace that idea. What a historic place has to offer visitors, after all, is historicity. To walk the same floors or look out the same windows that a great figure from history once did can be a powerful and inspiring experience.

“There’s some talk, I don’t know if it will happen, of rebuilding the house,” Joiner said. “If we rebuilt it, it would not have historicity, and it would not be eligible for the National Register, but it would work well as a small museum honoring Antoine.”

Glass was more enthusiastic about the idea of a replica or model of the home. “With the history of the C. C. Antoine House, hopefully young people would draw some type of inspiration from it, to know that this man came from their part of town and became lieutenant governor,” Glass said. “With the house being gone, there’s nothing tangible to see. The community lost a great piece of history when that house was destroyed.”

Lee, a lifelong activist and community organizer, situated the burning of the C. C. Antoine House within the broader context of what he said were rising racial tensions in Shreveport and beyond. Historical sites like the C. C. Antoine House—sites which celebrate the history of minority populations and often lack any kind of security apparatus—make easy targets for vandals, arsonists, and extremists, Lee said. He pointed out that other historical sites in Allendale have been lost to suspicious fires in recent years, including Shreveport Fire Station No. 4, a decommissioned firehouse built in 1912 to serve Allendale and the surrounding historically Black neighborhoods. The firehouse was burned on Friday, June 12, 2020, a week after the busts of four Confederate generals were removed from the Shreveport courthouse and just days after a massive Black Lives Matter protest was held in downtown Shreveport.

The house ca. 1995. Northwest Louisiana Archives, LSU Shreveport .

Lee is not the only person to connect the dots between ongoing social unrest and suspicious fires that have claimed several landmarks related to Black history in Shreveport. “It was absolutely arson,” Joiner said of the fire that destroyed the C. C. Antoine House. “The only question in my mind is: Was someone trying to kill that history? Because there are a lot of people out there who are afraid of history, afraid of icons, afraid of what they symbolize.”

Lee said that, even though Antoine’s house is a complete loss, there is still historicity in the soil and asphalt of Perrin Street. The arsonist didn’t burn everything, in his opinion. “The story of C. C. Antoine is still there, and it’s the stories that make any piece of land unique,” Lee said. “We may have lost the physical manifestation of C. C. Antoine for now, but his spirit is always going to be right there on Perrin Street.”

Chris Jay is a freelance writer from Shreveport, Louisiana, who is currently living and working in Round Rock, Texas. His writing often focuses on the food, people, and culture of northwest Louisiana. He recently completed his masters thesis on stuffed shrimp for the Graduate School at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches. Read more of his writing at stuffedandbusted.com.