Summer 2017

It’s In The Water

Powerful forces in New Orleans turned fluoride into a Cold War battle

Published: June 22, 2017

Last Updated: April 29, 2019

Louisiana now has a law on the books, the Louisiana Community Water Fluoridation Act of 2012, which mandates (with no funding supplied) that all 1,400 Louisiana water systems with more than 5,000 connections add fluoride. The fourteen-member Fluoridation Advisory Board, created in 1999, has a majority of practicing dentists as members, but fluoride is not in everyone’s water in the state. And systems need not add fluoride if the state doesn’t fund it, or if 15 percent of registered voters petition to put it on a local ballot and the voters don’t support it.

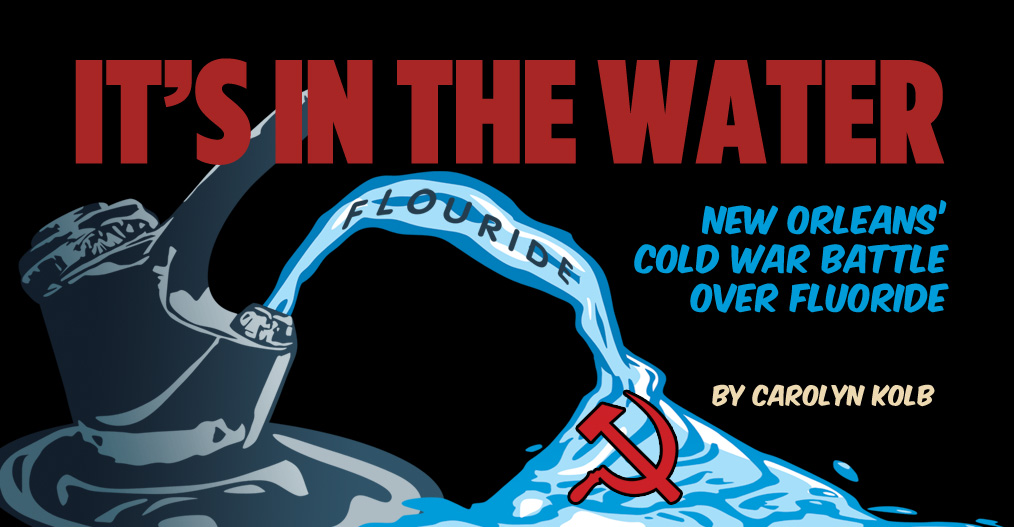

There has been consistently strong support for adding fluoride to public water supplies after its benefits became widely known in the 1940s. Fluoride in large amounts is poisonous, and there are other ways to prevent tooth decay, but public fluoridation has proven to be an overall safe and effective way to protect the teeth of large numbers of people, including those too poor for fluoride treatments at a dentist’s office.

Yet the science involved was only one part of the post-war fluoride discussion. While arguments against fluoridation appeared in mainstream, peer-reviewed scientific research, the anti-fluoridation movement was more focused on the threat of Communism and fear of federal government control, with scanty scientific underpinnings.

Satire of the fluoridation fight was part of the plot of the 1964 film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. As Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper (actor Sterling Hayden) explained: fluoridation coincided with “your post-war Commie conspiracy . . . A foreign substance is introduced into our precious bodily fluids without the knowledge of the individual, and certainly without any choice. That’s the way your hard-core Commie works.”

The Sewerage & Water Board of New Orleans first heard an official report on fluoridation on June 12, 1952. Only on June 13, 1973, did the board finally approve adding fluoride.

In this scene from Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Ripper tells Mandrake that he discovered the Communist plot to pollute Americans’ “precious bodily fluids” during “the physical act of love.” Courtesy of Columbia Pictures

From the 1950s administration of Mayor deLesseps Morrison (who took no position on fluoride) to that of Moon Landrieu in the 1970s (whose board appointees approved adding fluoride), there was one significant change in the city: African Americans, whose vote had helped elect Landrieu, were becoming the majority in the city’s population. Putting fluoride into the city’s water would be especially important for the dental health of the poor, a disproportionate number of whom, in New Orleans, were African American.

Albert Baldwin Wood was General Superintendent of the Sewerage and Water Board until his death in 1956. Wood was known for his many inventions, including his efficient screw pumps—some of which are still in use in New Orleans drainage stations. Wood was against fluoridation, calling it “medication of water” and admitting, “I don’t like it.” He told The Times-Picayune on May 1, 1951, that he felt New Orleanians might drink more water than other people, thereby potentially consuming an unhealthy amount of fluoride, but he offered no proof of this.

In an editorial on April 29, 1951, The Times-Picayune cited the support of fluoridation by the state dental society, the Young Men’s Business Club, and the Chamber of Commerce. The paper insisted that the board and Wood’s “initial objections seem easy to overcome,” because “fluoridation has long since passed the experimental stage.” But the editorial did not sway the water board.

The Sewerage and Water Board, at the June 12, 1952, meeting, reported in the meeting minutes:

The Special Counsel submitted [a] statement with reference to the fluoridation of the public water supply, which was approved by the Committees and referred to the board for ratification. The Committees recommended that the Board neither endorse nor reject the fluoridation of the public water supply of the City of New Orleans at this time. The matter is of such great import to the health of the people, that such a question should not be determined until all the scientists in this field will have had an opportunity to assemble their experiments and will have reached the definite conclusion that the addition of fluorine to the public water is a safe and harmless procedure.

When The Times-Picayune reported on the board’s negative decision the next day, it was obvious that the Sewerage and Water Board was beginning to rely on outside experts for their anti-fluoridation campaign, quoting from testimony at a Congressional committee hearing on fluoridation of Washington, DC, water. Although Congress in fact approved fluoridation of water in Washington, DC, after this hearing, the New Orleans Sewerage and Water Board distributed only the anti-fluoridation statements to their customers.

Opposition to Communism was not a prerequisite to being an anti-fluoridationist, but information from outside sources often combined the two topics—anti-Communist rhetoric was typically delivered alongside an anti-fluoridation message. Prominent voices in the community took up the fight. Crawford Ellis, a citizen member of the Sewerage and Water Board, was 1914’s Rex, King of Carnival, and a founder of the Pan American Life Insurance Company, with extensive ties to Latin America. He was vehemently anti-Communist and was also against fluoridation.

On July 8, 1954, the New Orleans City Council began planning public hearings on fluoridation on August 12 and 19 of that year. The Times-Picayune welcomed the idea, saying it would “provide an opportunity for interested organizations to lay the case before parents and citizens, and for opponents to present their side.” The editorial suggested that testimony be taken from health officials from Louisiana towns where residents drank naturally occurring fluoride in their water: “Such testimony seems badly needed . . . to resolve tantalizing questions.”

The Sewerage and Water Board was, of course, represented at the hearings, with George Piazza, the board’s attorney, speaking for one hour and twenty-five minutes, including a reading from one of the anti-fluoridation establishment’s favorite books, Charles Eliot Perkins’s The Truth About Water Fluoridation, a 1952 product of the Fluoridation Educational Society of Washington, DC. The Chamber of Commerce’s Medical Committee sent a proponent of fluoridation to the council hearings, as did the city medical society and the state board of health. The City Council, which could not bring about fluoridation on its own, was not completely unanimous on the topic. Finally the council decided to send a strongly worded note to the Sewerage and Water Board asking them if they would fluoridate.

In The Truth About Water Fluoridation, Perkins claimed to be “a biochemist and physiologist known for his discoveries in cancer research.” However, he is credited with no other publications besides the fluoridation book, in which he asserts fluoridation is “a planned experiment in mass medication, which is part of the technique of Communist philosophy to implant itself in American through mass control of the people by the State.” No biographical record of Perkins exists, and his name is absent from the 1952 and 1955 editions of American Men of Science, a comprehensive guide including some ninety thousand practicing scientists in the nation.

The Perkins book also was used in the Sewerage and Water Board’s own hearing on September 9, 1954. Crawford Ellis, citizen member of the board and vociferous anti-Communist, read from it, concluding, “I feel that the Board has sufficient information and evidence to warrant a definite vote against the use of fluoride in our City’s water and I am prepared to vote accordingly.” Then he ordered put into the record a letter from Alvin Baldwin Wood, the General Superintendent of the board, which stated, “I do not believe that the Sewerage and Water Board should add fluoride to its water supply . . . contrary to the mandate on which the Sewerage and Water Board has operated since its inception, namely the furnishing of the purest water that can be supplied to the city of New Orleans.”

Councilman-at-Large and board member Victor H. Schiro (who would succeed Morrison as Mayor in 1961) then offered an anti-fluoridation resolution. In the discussion that followed, it became apparent that, while Ellis might have the majority of votes at the Sewerage and Water Board hearing, there were various shades of opinion among the members. Even after his lengthy reading from the Perkins book at the City Council meeting just two months earlier, George Piazza told the Sewerage and Water Board that he couldn’t make up his mind on the issue.

Finally, the board approved a resolution “that until such time as Biochemists, Scientists, Medical Doctors and Dentists agree that the Sewerage and Water Board can add [fluoride] to the public water supply and that same will be PURE water as provided for by law, we cannot agree to put same into the public water supply of the city of New Orleans.”

The board then voted to appoint a medical committee to study the problem. Star of that committee was Dr. Alton Ochsner. When Ochsner first came to New Orleans to replace the famed Dr. Rudolph Matas as head of surgery for Tulane University’s Medical School, the city felt it had won a prize. Battling with Louisiana Governor Huey P. Long over staffing at Charity Hospital, teaching a generation of surgeons, and co-founding Ochsner Clinic were only some of his praiseworthy actions. If Alvin Baldwin Wood was the deity of New Orleans engineering, Alton Ochsner was certainly in the pantheon of its medical realm. He was named Rex, King of Carnival, in 1948.

The medical committee met for nearly two and a half years before issuing a final report firmly against fluoridation in April of 1957. “It is quite apparent,” the report concluded “that the majority of the members of your committee feel that sodium fluoride should not be added to the water supply of the city of New Orleans at this time and that further consideration be given to the study of this problem.”

Between the committee’s appointment and the delivery of its final report, occasional editorials ran in The Times-Picayune, usually regarding the approval of fluoridation in other places, and civic clubs such as the Young Men’s Business Club discussed the issue from time to time. The most interesting fluoridation news, however, was the anti-fluoridationist position of Alton Ochsner. On July 28, 1955, Dr. Ochsner spoke to the committee against fluoridation. The Times-Picayune reported: “Dr. Ochsner asserted that until recently he favored the fluoridation of the city’s water supply . . . but that information provided him by Dr. [C. C.} Bass . . . had caused him to reverse his opinion on the matter.”

Dr. Bass had been retired for fifteen years from his position as Dean of the Tulane Medical School, and in that time he devoted himself to the study of the effects of fluoride. “His studies led him to believe that those from sections of the country where fluorides are found naturally in the water had fewer cavities,” but an increase in gum diseases, Bass told a later meeting of the committee, according to The Times-Picayune. The fact that Bass had not apparently published this study in refereed journals, nor had his primary career been concerned with this, seemed to mean little to Ochsner.

There may have been another reason that Ochsner would suddenly become convinced to come out against a widespread preventive health measure, and it came from hard personal experience. During the early 1950s, epidemics of poliomyelitis ravaged the nation, and a vaccine against polio was eagerly awaited. When Dr. Jonas Salk announced one, and it was successfully tested, the nation eagerly awaited distribution. The vaccine was produced in a small quantity for wider testing.

In Alton Ochsner: Surgeon of the South, Ochsner biographers John Wilds and Ira Harkey report that “Ochsner used his influence to obtain a supply, and . . . 241 persons, including the children of Clinic doctors, were inoculated.” The vaccine batch was produced by Cutter Laboratories in California, and some of the doses contained live polio virus. Ochsner’s first grandchild, Eugene Allen Davis Jr., aged two and a half, was vaccinated April 26, contracted polio, and died on May 4, 1955. After numerous polio cases were diagnosed in those vaccinated, the vaccine was recalled on April 27 and subsequently destroyed.

Ochsner maintained his anti-fluoridation stance but was quoted as saying that “most of those on his side of the question were crackpots.” Before an April 26, 1961, meeting of the Civic Affairs Committee of the Chamber of Commerce, Ochsner seemed to soften his opposition, saying that perhaps time would provide positive results of fluoridation.

Because of his respected position in the medical community and in New Orleans, Ochsner’s anti-fluoridation opinion was a blow to pro-fluoridation forces. The Ochsner Papers at The Historic New Orleans Collection contain numerous letters from physicians pleading with him to reconsider. Those pleadings went unheeded.

Ochsner joined many other anti-fluoridationists in one aspect of his beliefs: he was a staunch anti-Communist and longtime president of the Information Council of the Americas. Founded in the wake of the Cuban revolution, INCA sponsored speakers, held rallies, made films, and broadcast anti-Communist messages. Its board of directors included John Ruddoch, successor to Crawford Ellis as head of Pan American Life Insurance.

New Orleans may have gone on forever without the benefits of fluoride, but a young Councilman Maurice E. “Moon” Landrieu took up the cause, and when he took office as Mayor in 1972, he put it back on the agenda. Various machinations to please the City Council (some members of which were still strongly opposed to fluoridation) held off the Sewerage and Water Board vote, and, unlike Morrison, Landrieu was present for the board’s meeting on June 13, 1973.

Voting against fluoridation came from three Councilmen members, Joseph V. DiRosa, James A. Moreau, and Clarence O. Dupuy Jr. Landrieu voted for fluoridation, as did all other water board members present and voting. This time the membership of the Sewerage and Water Board included an African-American, Alden McDonald, and the first woman member, Anne Milling, who both voted for the measure.

Anne Milling, when asked in March 2003, why fluoridation passed back in 1973, commented, “We just thought it was good for the community.”

The main difference in the outcome of the vote may have been the political climate of the city. Landrieu had been elected with African-American voter help and had promised to make city hiring racially fair. Landrieu’s administration, besides being racially inclusive, was refreshingly open to nationally accepted practices for governing a modern city. Adding fluoride to the water system was seen as a simple public health measure that would benefit the population, safely and at minimal cost.

New Orleans water fluoridation began in June of 1974, and since that time (with a two-year hiatus after Hurricane Katrina) “a small dose of fluorosilicic acid …which adds fluoride to the drinking water to aid in the prevention of dental cavities” is added to New Orleans water, according to the Sewerage and Water Board’s website. A 2014 report from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention found that 66% of Americans drink water with miniscule amounts of fluoride. Louisiana ranked 45th in the nation, with 44.2%.

Carolyn Kolb, PhD, is a native of New Orleans and the author of New Orleans Memories: One Writer’s City, a collection of essays she wrote for New Orleans magazine. She holds a doctorate in Urban Studies/ Urban History from the University of New Orleans.