Magazine

James Burton: Defining Rock and Roll Guitar

Legendary guitarist James Burton sits down for a chat with David Johnson

Published: December 1, 2015

Last Updated: February 24, 2021

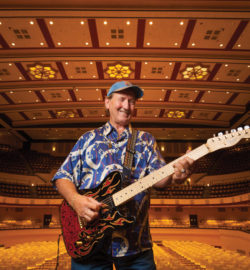

Photo by Rick Olivier

James Burton on stage at Shreveport's Municipal Memorial Auditorium, site of his debut on the Louisiana Hayride in the early 1950s.

David Johnson: Let’s start back at the very beginning. When did you first pick up a guitar?

James Burton: Well, I probably picked it up somewhere between 5 and 12. I actually started playing at the age of 13.

My first guitar was acoustic, yeah. As soon as I played a few chords, I think I learned to play Wildwood Flower, probably one of the first instrumentals. Chet Atkins and Roy Travis, Les Paul, they were my heroes.

I pretty much went professional at the age of 14. That’s when I was playing on the original Louisiana Hayride with the staff band.

Of course, you know, I wrote a little song called Susie Q. It was a guitar lick. I made a little instrumental around it, that guitar lick. I was working with a guy named Dale Hawkins, had a blues band. We played all the clubs in Bossier City—every club they ever invented here and then some. I was underage so I had to get a permit to go in the club to play.

You know they called the Bossier City Strip the mini Vegas strip. It was like Las Vegas, yeah.

Johnson: That required your parents’ permission?

Burton: Well, my parents had to get a permit from the courts, from a judge … I could only go and perform on stage, then leave. When I walked off the stage, I had to leave the building. At the age of 13, 14, that was worth it.

Johnson: Tell me more about performing at the Louisiana Hayride? What was the atmosphere there? Especially since you were so young.

Burton: It was an interesting show. They had a lot of great artists. I mean guys like George Jones, Johnny Horton, Jerry Lee Lewis, Bill Walker, and later on you had guys like Elvis. He came later, of course.

Johnson: Did they treat you like a kid? Or were you treated like a professional musician there?

Burton: I think they had a lot of respect for me because I guess I probably played pretty good and they didn’t want to run me off. I had a lot of fun. You know, Floyd Cramer was our piano player back then, and Jimmy Day, a great steel guitar player. Of course we had Sonny Trammel who played the three-neck Fender steel.

Johnson: So you had been listening to these men on the radio as a kid?

Burton: Yeah, I’d listen to them on the radio. I was raised on country music and then I got into rhythm and blues. It was just a constant music thing for me. My mother said that when I was a little boy, I’d run around the house beating on broomsticks and everything I could find, pretending like I was playing guitar. I loved listening to music. You could say I was in Nashville before I was born. I never took any lessons. It was basically, you know, what you pick up from hearing things and playing records and learning chords.

Johnson: Did any of the Hayride perfomers come and help you, maybe share a technique with you?

Burton: Not really. I think they were trying to steal my licks. [Laughter.] You know, it’s amazing what you can learn from working with professional people in the business, and paying attention to what they’re doing and try to take what they’re doing and improve it. That’s basically where I was at. I would play 45 records, and I would get my guitar and I’d tune it. I probably didn’t know exactly what key they were in, but I’d tune my guitar to the record, and I’d play along with the record.

You know what I caught myself doing? I wasn’t copying what they were doing but adding something to what they were doing. Like Chuck Berry, you know normally you’d pick up and play that Chuck Berry rhythm. I didn’t do that, I did something to add to it which was a little different.

Johnson: You have your own very distinct sound. No one sounds like James Burton.

Burton: There’s a bunch of them out there. A bunch of J.B.s out there. You know what? They all give me credit. Let me show you this framed email from Paul McCartney. Read it.

Johnson: “Dear James, I want to wish you a very happy 75th birthday, and let you know how much I have loved your work for many years and what a hero you are to me and many of my generation. Keep rockin’ and have a great party. Love, Paul McCartney.”

I wanted to talk with you again about Dale Hawkins and Susie Q. How did you come to know him and record that song?

Burton: Dale had a blues band and we connected. Him and his brother Jerry … Jerry had a band and Dale had a small band. A lot of musicians sort of intermingled. They would play, everybody would all get together and play together. I actually started playing with Dale in the clubs. Stan Lewis’s brother, Ronnie Lewis, played drums. So we had a good little band, T. J. Bandini playing bass. We just played all the little club circuits.

Susie Q was recorded here in Shreveport, but let me tell you how this all came about. I wrote that little instrumental. We didn’t have a name for it, but it was the most requested song of the night at the clubs, just the instrumental.

Dale said, “Man I gotta write some lyrics to this.” So he came up with the idea with the lyrics: “Susie Q. I like the way you walk. I like the way you talk.” Very simple lyrics. The feel was there, a good funky little thing.

As soon as we’d play it, the crowd would hit the dance floor. It was the most requested tune.

We went in and recorded it at KWKH [a Shreveport radio station that broadcast the Louisiana Hayride]. It was incredible. I think we only had three or four mikes. It was a small group thing, the drum, stand up bass, and the guitar. And the rest is history.

That song … I was 15 years old when we recorded it, Dale was 16. We were underage when we recorded it. You learn about the business after you get in to it. I tell my students that want to play guitar, “Playing guitar is only part of it. You’ve got to learn a little bit about the business.”

Johnson: I know you played with Ricky Nelson and you wound up on The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet television show. How did that happen?

Burton: Well, after I left Dale, I was working with a guy name Bob Luman, a great country singer, and we played at the Hayride together. Then we traveled around, actually went to California. We did a movie called Carnival Rock, when I was 16. I met Ricky around that time, around ‘57. We were rehearsing a song called My Gal is Red Hot, a Billy Lee Riley song. We were actually in Lou Chudd’s Imperial Records office on Hollywood Boulevard and Ricky came in on business with Jimmy Haskell, a music arranger on the Ozzie and Harriet show. They stayed for about three hours and we were jamming, playing, having a good time. The next day I received a telegram at our rental house inviting me and bass player James Kirkland to meet up with Rick.

We met his mother and father and everything during that time and Ozzie said, “Boy this is great, can we do a couple songs on the show?” Ricky was 16, and I was 16, just a few months apart. We kind of grew up together.

I came home for a little vacation during the holidays, back to Shreveport, and they sent me another telegram. Ricky and Ozzie said that they would very much like for me to be his lead guitar player.

I said, “Well, I gotta go for it.” That was the beginning of the rock and roll thing.

Later on, I did this TV show, Shindig, where I was asked to play slide dobro with Johnny Cash. Jack Good, the producer, was a big fan, he said “ I love all the guitars solos on Ricky Nelson records,” and he said “You must be on this show every week, you must be a regular on the show.” He said, “Well lets put a band together, you’ll be the Shindogs.” It was the number one show for one year. Then Jack went on to some other things. The other producers took over and Jack left. Then the show just kind of faded away.

Johnson: You went on play with so many icons of music. I wanted to toss a few names at you. I know you worked with Frank Sinatra—

Burton: Oh, he was great. Very nice man. Doing recording sessions only, I didn’t do any travel or anything, just recordings. He would come in, he’d say hello to everybody, talk. Sometimes he’d come in and say, “Well, I’m not in good voice today but I’m going out to Palm Springs and play some golf with Dean [Martin]” and all the other golfers.

We had sessions booked, we had like three or four sessions booked in a studio with 60 musicians, so to cancel that many people and still have to pay all the fees—he would do it because he didn’t feel like his voice was just prime for that day. You know, a guy like him could do that.

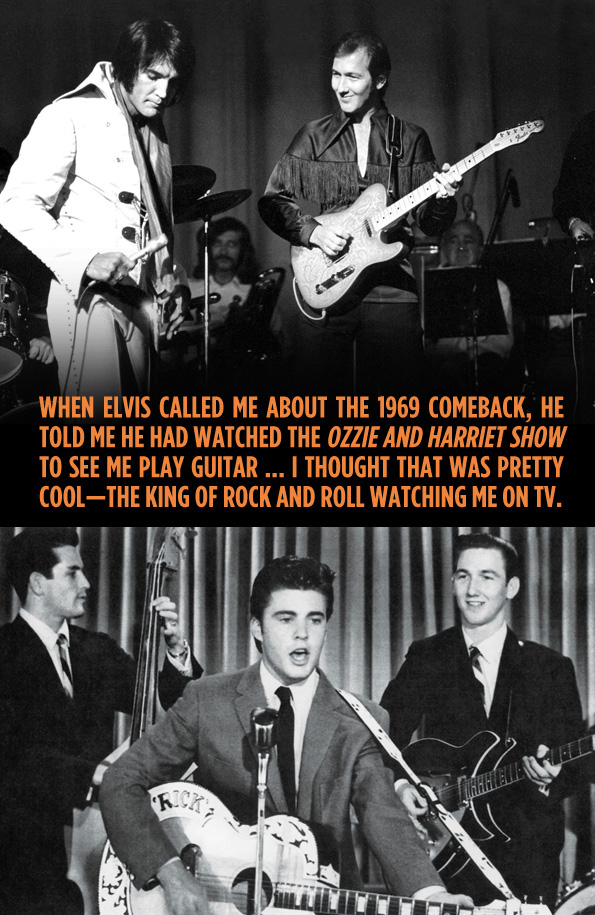

James Burton played guitar for Elvis Presley’s TCB band from 1969-1977 (top); James Burton was Ricky Nelson’s backup guitarist on the Ozzie and Harriet TV show in the late 1950s. (bottom). Courtesy of James Burton

Johnson: I know you caught the attention of Elvis. He called you in 1968?

Burton: Yeah, he called me in ‘68 to do his Comeback Special. But I was not available for that, at that time. We were in the studio with Jimmy Bowen, the producer with Frank Sinatra at that time, so I couldn’t get out. Timing you know? I was very busy when I had the call from Elvis because I was working with all the artists in the studio.

We were doing five sessions a day, seven days a week. It was crazy. Anyway, it was a tough decision. Elvis called again, and I almost had to turn Elvis down a second time because I was so busy. I looked at my schedule and said, “Well, as crazy as it is, I’ll call my clients and check with them.” Everybody I called said, “Aw, man, go do it! We’ll put sessions on hold or you can always come overdub. You’re not losing anything, just go for it.” So I did. I said, “This is going to be great.”

Johnson: You then joined Elvis at the International Hotel in Las Vegas?

Burton: That’s when we opened, August 1969. The house was full of incredible celebrities and movie stars. Elvis was a little nervous about the comeback, doing nothing but movies for nine years. When he called me, we talked for two or three hours on the phone. I was late for a recording session that day, I was late getting to my session because I was talking to him so long on the phone. The opening conversation, he said, “I watched the Ozzie and Harriet TV show to see you play guitar and Ricky sing.”

I thought that was pretty cool. The King of Rock ‘n’ Roll watching me on TV. He was a great guy and it was an interesting nine years working with him.

Johnson: I’ve read that Elvis was a prankster. Was he fun to work with?

Burton: Yeah, you know he was always playing jokes on everybody, but he didn’t take them too good.

Elvis was always all over stage. The band, we’d have to watch him, pay attention. You couldn’t take your eyes off of him because you never knew what he was going to do next. Anyway, one of the guys came up with the idea to put some marbles out on stage, so when Elvis comes out, the curtain goes up, he’s dodging all these marbles. Which is kind of dangerous really.

Elvis got word on who might be the suspect. The conductor, Joe Guercio—bless his heart he passed away a few months ago, last year—it was a night or two later, after Joe got off work, about 2 in the morning. He got home about 2:30 or 3 and went to bed. As soon as he got in bed, the doorbell rang. He got up and went to the front door, and it was a huge semi-truck out front. The driver is standing at the door, and said, “I have a delivery for Mr. Joe Guercio.” Joe said “Yeah, leave it at the front steps here, I’ll get it in the morning. I gotta go to bed.”

So he closed the door, and the next morning when he got up, it’s about noon, he went to his front door to get his paper, and there must have been five million marbles all over his yard! It was incredible.

Johnson: Only Elvis could afford payback like that.

Burton: Elvis was just a fun guy to be around but real serious at his work. We’d rehearse a show, make out a list of songs. We’d all have a song list, but you might do the first four tunes and after that, forget it. He’d jump all over.

Playing at Graceland was fun, oh yeah. We would go in about 6 p.m., the band, we’d be ready to go. Elvis might come down at midnight or 1 o’clock in the morning.

Then Felton Jarvis, the producer, would say, “Now listen, when Elvis comes down, nobody yawn. No yawning while Elvis is with us.”

Johnson: Tell me about your foundation here in Shreveport.

Burton:It was 2005. I’ve always wanted to do my own show, invite my own artists and you know, my friends, bring them to Shreveport. I made some calls, and put the show together. During all of this, I was thinking I wanted to do something for the kids. I thought now is a great time to form the James Burton Foundation, do my shows, invite my artists to work at a benefit to raise money to help the kids with music in schools, and to buy guitars for different functions. We went to Saint Jude’s [Children’s Hospital in Memphis] and gave guitars to kids there for a program. The Shriners, the veterans home, and so on. We got music back in schools by giving guitars to teachers. You know, the first time we gave the guitars to the kids, but we figured out the best way to do it is in the school. Let the school furnish guitars to the students while they’re teaching them.

We put in a couple recording studios here at my Foundation so the kids can come and record, and maybe we could get them on DVD and let them see how they’re progressing, to learn the music business and everything.

Its just a great thing to help the kids. You know, they’re going to take over our legacy when we’re gone. We want to help them, give them the best knowledge that we can.

—–

For more information about the James Burton Foundation—and plans for a music museum in Shreveport—visit jamesburtonfoundation.org.