Sound Advice

Last Gig in Natchitoches

Jim Croce died shortly after playing at Northwestern State University

Published: December 1, 2021

Last Updated: February 28, 2022

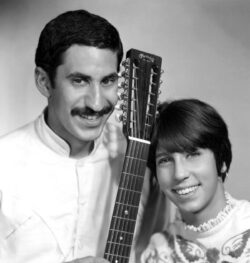

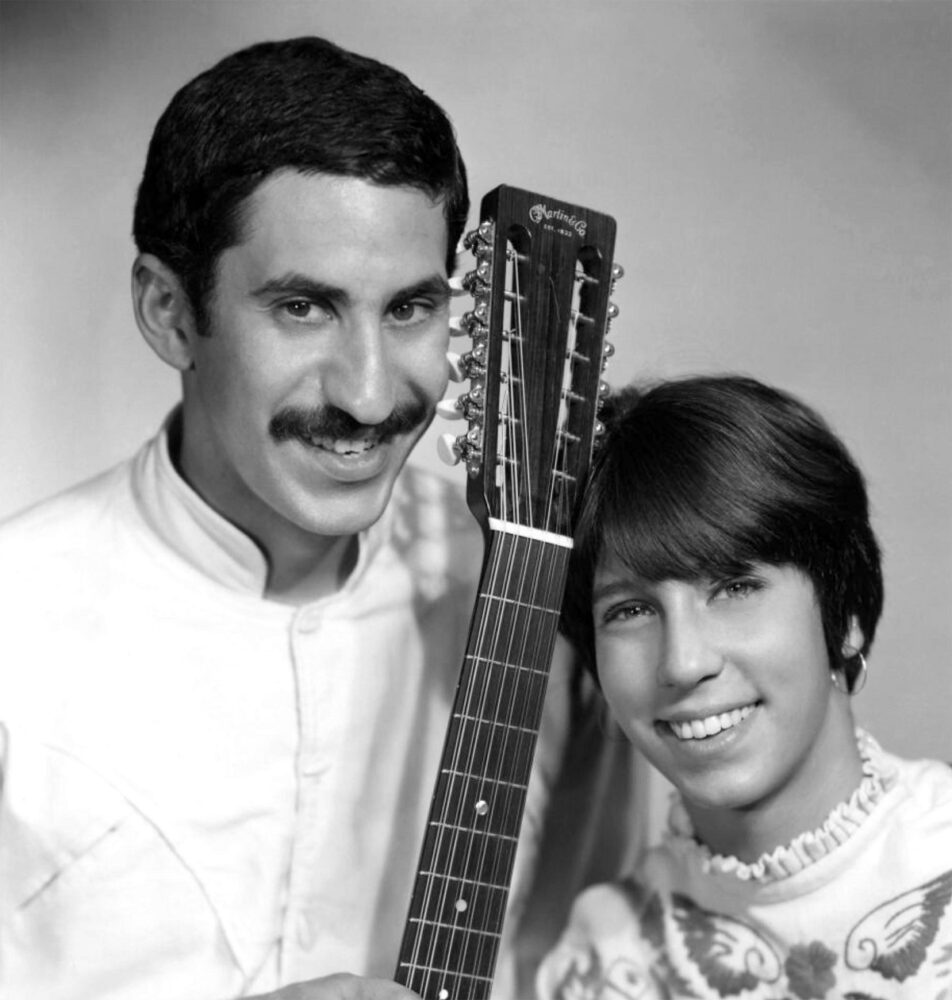

Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Jim and Ingrid Croce in a publicity image, ca. 1966.

“An hour later, after closing with ‘Bad, Bad Leroy Brown,’” the students wrote, “he was dead in the wreckage of an airplane.”

Croce was traveling on a small chartered plane, a twin-engine Beechcraft with just enough seats to squeeze in himself, his road manager Dennis Rast, and his booking agent Ken Cortese, plus comedian George Stevens, who’d opened the show, and 24-year-old lead guitarist Maury Muehleisen, whose chemistry in the studio and onstage with the songwriter appeared to be an engine of his recent success. All five men, plus pilot Robert Elliott, were killed when the aircraft hit a pecan tree, just seconds after takeoff, and crashed.

The students’ review/news report/de facto obituary for Jim Croce, which was filed to United Press International’s wire, was headlined “Jim Croce Left Image of Honesty” in the Town Talk. Calling him “rough-hewn, mustachioed, cigar-smoking, weatherbeaten,” they wrote that his records were “honest and sincere, old-fashioned, not slick and spoiled by success.” A student they spoke to at the Prather show was quoted as saying “In an industry filled with freak acts, Croce was a welcome and much-needed change.” 1973 was definitely a good year to be an authentic, earthy folk-rocker. Croce, whose warmth and sincerity seemed as thick as his mustache, fit right in alongside simpatico stars like James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, and Carly Simon. Tender ballads like “Operator” and “Time in a Bottle” waxed alongside rollicking, character-driven songs like “Rapid Roy (The Stock Car Boy),” “Roller Derby Queen,” and the now-oldies’ station perennial “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown,” a whomping modern folktale that shares ancestry with old-time bad-man narratives like “Stagger Lee.” “Bad, Bad Leroy Brown” scored Jim Croce his first number-one hit in April 1972 as the second single from Life and Times, his follow-up to You Don’t Mess Around with Jim and the last album to come out while he was still alive. As a knockaround troubadour, he was the real deal, too: before catching a break in pop music, as his first big Rolling Stone interview detailed in September ‘72, the first-generation Italian-American had worked construction, driving a truck and welding. His first steady job as a musician was entertaining diners at a steakhouse on the outskirts of Philadelphia, where he’d grown up.

1973 was definitely a good year to be an authentic, earthy folk-rocker.

He’d come a long way to get to Natchitoches, and he was racking up a lot of accolades to show for the journey. But some reports, at least, imply that on that September night, nearing the end of a long tour, he was feeling the strain more than he was enjoying the spotlight. The decision to get on the plane that night and hustle on to the next campus show, at Austin College in Sherman, Texas, about an hour’s drive north of Dallas, was a last-minute call, too; the pilot had already checked into his motel for the night, expecting not to fly until the next day. According to the Monroe News-Star, which ran a piece the week of the crash’s 46th anniversary, in 2019, the pilot had no transportation back to the airport and had walked nearly the whole three miles, arriving “rattled, hot and sweaty” after getting lost along the way and wandering through a cornfield by mistake. Calvin Gilbert, a Northwestern student in 1973 who went on to become a music journalist, told the News-Star that even nearly 50 years later, he remembered how antsy the star had looked that night. “I saw Croce standing at the side of the stage chatting with some people, but mainly looking at his watch,” Gilbert said. “In retrospect, that’s evidence that he was anxious to get the hell out of there.” The student’s piece in the Town Talk had clocked the set as lasting barely thirty minutes.

With a poignant wrench worthy of one of his love songs, a week after her husband’s death Ingrid Croce received a letter Jim had posted from the road. In her 2012 book I Got a Name: The Jim Croce Story, she recalled he’d phoned her from Natchitoches before the concert. He’d made fun of the North-Louisiana take on Italian sandwiches that offended his Philly palate and told her he loved her and A. J., whose second birthday was coming up the next week—but, as she recreated his final night on the page, he was audibly frustrated with the slog of the road, annoyed at his manager for extending the tour another month, and more than ready to slow down. The letter promised just that, in print: “When I get back everything will be different,” he wrote. “We’re gonna have a life together, Ing, I promise. I’m gonna concentrate on my health. I’m gonna become a public hermit. I’m gonna get my Master’s Degree. I’m gonna write short stories and movie scripts. Who knows, I might even get a tan.

Give a kiss to my little man and tell him Daddy loves him. Remember, it’s the first sixty years that count and I’ve got 30 to go.”

After Croce’s death, his love song “Time in a Bottle,” written for Ingrid when she was pregnant with A. J. and released as a single in November 1973, hit number one. The Natchitoches Airport cut down the pecan tree.

A columnist since 2016, Alison Fensterstock has written for 64 Parishes about music, dogs, witches, hippies, and other things.

Sound Advice is funded in part by a grant from the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation.