The Last Thing I’ll Ever Write About Stuffed Shrimp

One writer’s crabmeat-filled obsession

Published: June 1, 2024

Last Updated: September 1, 2024

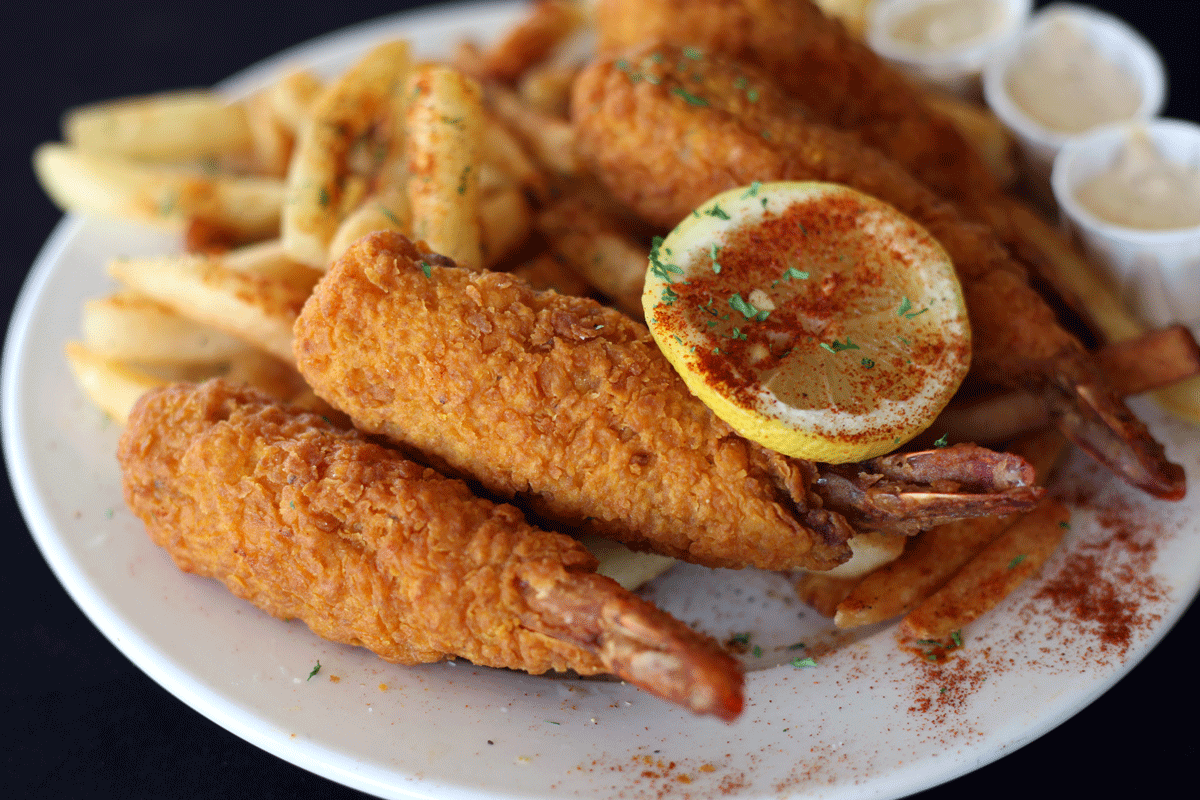

Photo by Chris Jay

Stuffed shrimp at Orlandeaux’s Cafe in Shreveport.

The “Observer Effect”—a concept from the world of physics which states that the act of observation changes the thing that is being observed—doesn’t only apply to subatomic particles. It also applies to stuffed shrimp.

It was a late summer afternoon in 2009, and I was in the middle of Allendale, a Shreveport neighborhood that local television news consistently paints as a hellscape of gang violence and urban decay. I was standing on the sidewalk across the street from C. C. Antoine Park, a well-kept public greenspace, admiring Connie Robinson’s tiny, canary-yellow C & C Café. On the side of the squat cinderblock structure, a mural showed stylized stuffed shrimp and fried chicken tumbling through abstract space. I stepped into the restaurant, excited for my first taste of a local delicacy that I’d heard so much about.

The breeze from the café’s single window unit kept slipping out, bit by bit, every time the screen door rattled open. Each new arrival made conditions in the restaurant less bearable, drawing annoyed glances from those already waiting in line. My first-ever order of Shreveport stuffed shrimp arrived in a Styrofoam container that strained audibly against the weight of the food. Carefully perched atop the container were three ramekins filled with remoulade, which the menu—as well as other patrons—referred to as “tartar sauce.”

A cook who introduced himself as Kool-Aid casually sat down next to me, and the two of us watched Michael Jackson’s funeral broadcast live from Staples Center while I ate lunch.

“End of an era,” Kool-Aid said.

For me, an era was just beginning. I spent the next fifteen years closely documenting a handful of Black-owned restaurants in Shreveport that are associated with a style of crabmeat-stuffed, deep-fried shrimp that I’ve only encountered in northwest Louisiana. This stuffed shrimp tradition began in the mid-fifties at a Creole- and Black-owned business in Shreveport called Freeman & Harris Café. As Black cooks left Freeman & Harris Café to open their own restaurants, they took stuffed shrimp with them to new areas of town. This process, over time, resulted in a citywide tradition that is still going strong more than seventy years later.

If fifteen years seems like a lot of time to spend writing about and researching one topic—especially something as seemingly inconsequential as stuffed shrimp—you’ll just have to take my word for it. In Shreveport, where knowledge of the traditions surrounding stuffed shrimp can change a family’s economic reality for generations, stuffed shrimp are serious business.

I would guess that, as of February 2024, I have published about twenty-five articles on stuffed shrimp for websites, magazines, newspapers, and broadcast media. Sometimes I was paid, and other times I volunteered. I started my own blog, Stuffed & Busted, in part as a hub for my stuffed shrimp research. I took hundreds of photos and videos documenting stuffed shrimp culture in Shreveport, shot and edited a short film, helped organize the first-ever Shreveport Stuffed Shrimp Festival, took elected officials to eat stuffed shrimp, organized fundraisers, hosted stuffed shrimp–themed city tours, held press conferences, and helped incorporate a nonprofit related to stuffed shrimp.

I outlined a proposal for a book about stuffed shrimp. I produced a set of posters illustrating the history of stuffed shrimp, printed them on foamcore, and carried them around in the trunk of my car with an easel, just in case I bumped into someone who needed to be schooled on the topic of stuffed shrimp. This past May, I successfully defended my 108-page master’s thesis for Northwestern State University, “Stuffed Shrimp as a Folk Tradition in Shreveport, Louisiana.” I did all of these things without realizing that, bit by bit, I’d begun to feel an illegitimate sense of ownership over a tradition that did not belong to me.

Around the time that I completed my thesis, I noticed a change in the way I felt about stuffed shrimp. Whenever I saw an article or post about Shreveport stuffed shrimp that I had not written, I felt resentment towards the author. Instead of celebrating and sharing the work done by others, I scanned it for errors. I was a dog guarding a bone, a prospector who’d staked his claim on the story of Shreveport stuffed shrimp. I told myself that I needed to step away from the topic, but invitations to write about stuffed shrimp kept showing up in my inbox. Because I loved many of the people and institutions involved in the tradition (and, honestly, because I needed the money), I never turned down an opportunity to spread the word. I developed a blind spot that prevented me from seeing what I had become, which is a white gatekeeper of Black culture.

It’s true: stories belong to everyone. They’re not the property of any individual, business, or organization. Also true: it’s easy to get carried away. Who didn’t get hired to write those articles, I wondered—the ones that I got hired to write? My hope is that future invitations to tell this story will find them.

Chris Jay is a freelance writer from Shreveport, Louisiana. His writing often focuses on the food, people, and culture of northwest Louisiana. Read more of his writing at stuffedandbusted.com.