Louisiana’s Special Squashes

The Thanksgiving season brings the region’s two favorite squashes to the table

Published: August 30, 2021

Last Updated: December 1, 2021

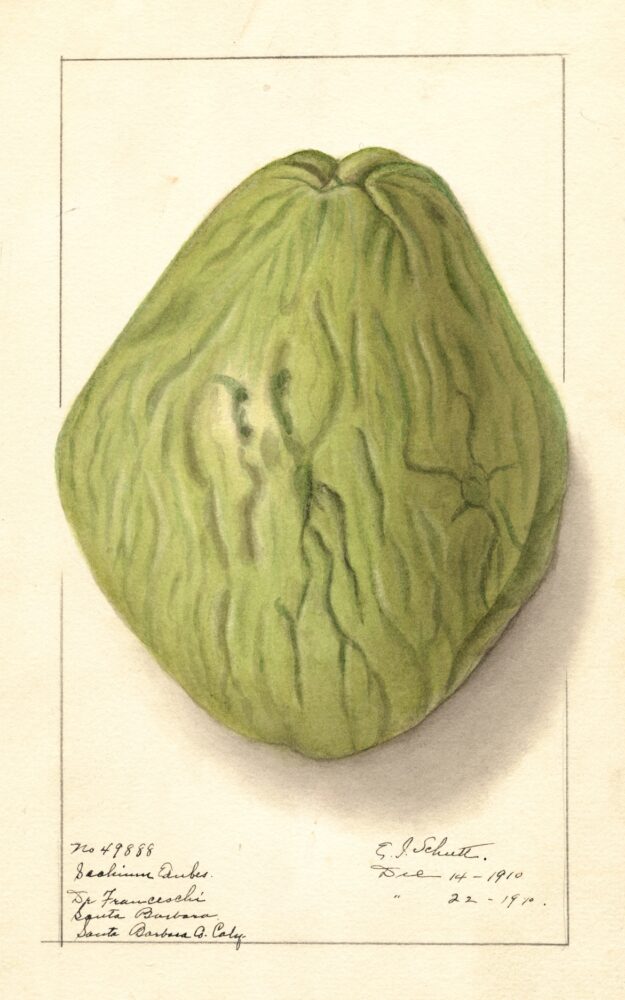

US Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection

A 1910 watercolor of a mirliton by Ellen Isham Schutt.

When I arrived in New Orleans in the 1990s, I knew nothing of cushaw, but rapidly learned that they are also known as Japanese cooking pumpkin or silver-seed gourd and are a cooler weather delight. The striated crookneck squash, although once ubiquitous, can be difficult to find these days. With luck, though, they can be uncovered at roadside farm stands and glimpsed being sold from the backs of trucks in parking lots. I also learned that two of my friends, Lolis Eric Elie and Lou Costa, were such partisans of the squash that they would go to incredible lengths to obtain them, including swerving across multi-laned highways and braking to a stop at roadside stands when they were spotted. I was a bit skeptical of their enthusiasm until I tasted the delicacy of the vegetable; I, too, became a fervent partisan with my first forkful of cushaw pie. It was light, as though pumpkin pie had been prepared by angelic hands. Now I am a convert.

…two of my friends… were such partisans of the squash that they would go to incredible lengths to obtain them, including swerving across multi-laned highways and braking to a stop at roadside stands when they were spotted.

Recently, a friend posted a picture on Instagram showing a bumper crop of cushaw available for sale at her farmer’s market on the North Fork of Long Island, New York. A transplanted southerner, she knew that she’d hit the mother lode and crowed proudly about her discovery, obtaining loads of likes and comments from cushaw-deprived Louisianans. I’ll admit I was among them.

If I am a relatively new convert to cushaw, I was more familiar with mirliton, the small, pear-shaped, light green vegetable with a bottom that looks like a gurning mouth. I knew that it was a vegetable of many names; I’d met up with it in the Caribbean, where it is known as chayote in the Spanish-speaking areas, chocho in Jamaica, and christophene in some of the French-speaking islands. I remember that it was called xuxu in Brazil. The Louisiana word mirliton seems to come from the Haitian word for the vegetable that is a member of the gourd family. Another mild vegetable, it is grated and dressed with a garlicky vinaigrette in Guadeloupe, breaded and deep fried in Brazil.

While the vegetable is likely to appear on the tables of the world at any time of the year, it, too, is a Thanksgiving table denizen in Louisiana, usually appearing baked and stuffed with a variety of fillings ranging from shrimp and crabmeat to ground beef. I cannot see a stuffed mirliton without hearing the voice of the late Queen of Creole Cuisine Leah Chase. In my mind’s eye, I see her speaking from her perch in her kitchen from which she directed all kitchen happenings, planning a menu for some gathering, saying, “OK Jess, let’s start them off with some stuffed mirliton.” I learned that the offering of stuffed mirliton was designed to signal to the guest that this was going to be a carefully considered traditional feast, one in which the ingredients were of the best quality and served in a classic manner. A shellfish allergy prevented me from ever tasting Mrs. Chase’s stuffed mirliton, and I deeply regret that, but I could always tell from the delighted smiles of all who indulged in it that they were indeed the treat I imagined them to be. I have eaten the variant that uses chopped beef instead of the more classic seafood, and I absolutely understand the enthusiasm.

In fact, as I celebrate this year’s return to my usual Thanksgiving table in New Orleans and to the dining world of the new normal, I’ll be seriously disappointed if I sit down and find that cushaw in some form is not among the offerings. Frankly, I wouldn’t be unhappy to see a stuffed mirliton signaling me from the sideboard as well.

Jessica B. Harris is the author, editor, or translator of eighteen books, including twelve cookbooks documenting the foodways of the African Diaspora. In March of 2020, she became a James Beard Lifetime Achievement awardee.