Magazine

When Lumber Was King

From 1900 to 1920, Louisiana was one of the nation’s top three lumber-producing states

Published: December 19, 2014

Last Updated: July 21, 2019

Houses like these fill the residential districts of Leesville, Alexandria, Minden and Ruston, and numerous other towns and villages. Louisiana’s abundance of timber provided the material for these houses and, more importantly, generated an economy that allowed towns and villages to flourish.

At the end of the Civil War, three-quarters of Louisiana’s land was forested, most of it with longleaf pine, 150 to 200 years old and reaching more than 100 feet in height. By the 1880s, out-of-state lumber companies, having exhausted the supplies of timber in their home states, came south to harvest these pines. As they surveyed the tall stands of virgin pine, their response surely echoed that of Timothy Flint, who traveling through the region in 1835, reported, “I have seen the pine woods of New England, and many others, but this grand and impressive forest is unique and alone in my remembrance … Millions of straight and magnificent stems, from seventy to a hundred clear shaft, terminate in umbrella tops, whose deep and somber verdure contrasts strikingly with the azure of the sky.”

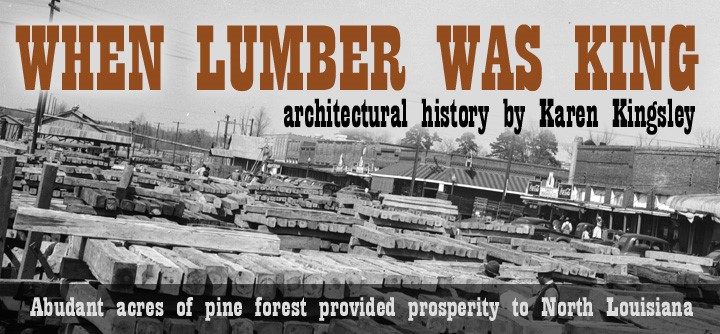

The railroads opened up the state’s vast timber reserves for exploitation and enabled the lumber companies to flourish. Logs could be transported more efficiently than by the bayous and rivers as before. Logging companies moved deep into the extensive pine forests that blanketed the central and northern parts of the state that formerly were inaccessible.

Lumber towns sprang up almost overnight. From 1900 to 1920, Louisiana was one of the nation’s top three lumber-producing states, along with Washington and Michigan.

The lumber companies built communities to house their labor force, accommodating them in “skidder towns,” next to the forests they were cutting down. These temporary settlements were relocated when the nearby lumber was exhausted. More permanent company towns were established around a sawmill. Almost everything in these towns — housing, commissary, school, church, theater or movie house, sometimes a library, and recreational facilities — was built and owned by the company.

The town of Fisher in Sabine Parish is one such example and still conveys the ambience of its early 20th-century character when it was owned by the Louisiana Long Leaf Lumber Company, known as 4L. Founded by John B. White and Oliver W. Fisher from Missouri, who purchased 75,000-acres of virgin timberland, the latter’s name was given to the town they built in 1899. The town was laid out on a grid plan, a quick and convenient way to lay out a town, here with approximately 130 houses. Typical of company towns of that era, employees were segregated by class and race. Though Fisher’s streets originally were unpaved, the town had wooden sidewalks. And of course all the buildings were constructed of wood, although the amount of decorative architectural detailing was considerably more on the managers’ houses.

From 1900 to 1920, Louisiana was one of the nation’s top three lumber-producing states, along with Washington and Michigan.

As well as the sawmill and the company office, 4L built community facilities for the workers: an interdenominational church, a hospital, a school, a hotel, and an opera house. The Opera House — an elegant name for a venue that hosted all different kinds of entertainment, including movies — is monumentalized with four wooden Doric columns supporting a pedimented porch. The Fisher Hotel was described in a 1908 newspaper as being known to all the traveling public as the best between Beaumont and Shreveport. When railroad service to the town ceased in 1968, the hotel was demolished and sold for lumber. As well as the houses, the company owned the commissary, or shop, where workers purchased all their supplies. Not all was ideal in this ideal town however; strife between ethnic groups and labor unrest and union organization is recorded. Much later, in 1966, the mill was taken over by Boise Cascade and the homes were sold to the residents.

If Fisher gives us a glimpse into the community aspects of an early 20th-century lumber town, the industrial side of the lumber world is encapsulated at the Southern Forest Heritage Museum at Long Leaf in Rapides Parish. This 57-acre historic site preserves and interprets buildings and artifacts that survive from its days as a sawmill complex. The museum opened in 1998 after acquiring the site and surviving buildings after the sawmill ceased operations in 1969. Caleb T. Crowell and A. B. Spencer founded the Long Leaf Lumber Company in 1892, naming it Long Leaf in recognition of the longleaf pine that would supply their mill. They built a spur from the Red River and Gulf Railroad to transport the lumber. Today the museum site offers a feast of lumber memorabilia with its collection of structures that include drying kilns, a boiler house (which burned waste wood to heat water for steam power), a planer mill where lumber was finished and smoothed to make it ready for market, and the Clyde skidder that dragged logs from the forest to the trackside. The approximately 160 houses for the workers are gone, but the mill manager’s house survives and is now used as the museum’s office.

Other long-established towns prospered as centers for their area’s lumber industry, among them Minden, Winnfield, and Mansfield. Handsome banks and shops lined their main streets. But most of the towns constructed solely to serve this single industry have fared badly. When the lumber was exhausted, the mill would close and the town abandoned. Little survives at Fullerton in Vernon Parish, and the sawmill complex has disappeared altogether. Established by the Gulf Lumber Company in 1907, with S. H. Fullerton as president, the town’s population numbered approximately 3,500 in 1924 and boasted the second largest mill in the South. After 97,000 acres of longleaf pine had been cut down, the mill shut down in 1927 and the town emptied. Fullerton Park now occupies the mill site. And only fragments of the now demolished concrete five-story alcohol plant (grain alcohol made from chips of the longleaf pine) can be glimpsed from the park’s nature trails.

At Clarks, in Caldwell Parish, where the Louisiana Central Lumber Company established itself in 1902, the company built a handsome two-story multi-purpose building that housed the post office, barber shop, confectionery-drugstore and a lodge hall on the second floor. It became known as the Oasis. The mill closed in 1953 and other than the Oasis, only a few houses survive.

By the late 1920s, 70 percent of Louisiana’s pine forest had been cut, most of the mills closed, and the company towns all but disappeared. But an important start in reforestation was made by Henry Hardtner, who founded the Urania Lumber Company in La Salle Parish in the 1890s. His was one of the earliest lumber enterprises to incorporate reforestation and sustained-yield forestry. Then in the 1920s, the Louisiana Division of Forestry purchased forests in central Louisiana to demonstrate what could be achieved with proper timber management. And the U.S. Forest Service purchased 10,000 acres in Natchitoches Parish to create the Kisatchie National Forest in 1930.

Pines continue to supply the sawmills and paper mills, although these have now consolidated into just a few companies. Nevertheless, driving the roads of central and northern Louisiana today, the lumber industry is still visible — from the endless stands of pines, to the trucks hauling piles of logs from forest to mill, the odor of the pulp and paper mills, and the arching streams of water hosing the mountains of stacked logs to keep them damp for the mill. Echoes of the forests and the industry are reflected in the names of such towns and communities as Pineville, Yellow Pine, and Good Pine.

——–

Karen Kingsley is the former director of the Southeastern Architectural Archive at Tulane University and author of The Buildings of Louisiana, published by Oxford University Press in 2003.