Mama Oretha and Tee Jean

Family memories of two civil rights icons

Published: November 30, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Oretha Castle Haley at an event at Dooky Chase’s, ca. 1984.

Born in the post-Reconstruction Jim Crow South, right outside Memphis, the Castle sisters—soon to become a trio of siblings with a baby boy, John Castle—found their purpose in the movement once the family relocated to New Orleans in the late ’40s. My great-grandmother Vergie Castle (I called her MaDear) and great-grandfather John Castle, who died before I was born, were hard-working people. My great-grandfather worked as a longshoreman and later as a taxi driver. My great-grandmother was the bartender at the world-famous Dooky Chase’s restaurant which, because of my grandmother’s involvement in the movement and the restaurant’s proximity to the house on North Tonti where they lived, became a hub for civil rights leaders and workers.

Mama Oretha began her freedom-fighting journey while she was a student at Southern University at New Orleans. She joined the economic boycott on Dryades Street being led by the Consumers’ League of Greater New Orleans, the first demonstration of its kind in New Orleans. After that initial protest, she began organizing and exploring with friends other ways they could get involved. These meetings at the Dryades YMCA eventually led to them reaching out to the national civil rights organizations and ultimately the formation of the New Orleans chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE).

Mama Oretha would become president of the CORE chapter, making her one of very few women leading a civil rights organization at the time. She famously co-organized, led, and gave a keynote address at the 1963 Freedom March in New Orleans, which is still the largest demonstration for civil rights in New Orleans history. It would not be long before my great aunt, Tee Jean, would follow in her big sister’s steps and dive into the movement. She was a fighter, not necessarily the leader and organizer Mama Oretha was, but that worked well for balance. Tee Jean immediately understood the assignment “Get in good trouble!”

In the early 1960s, Mama Oretha led protests, demonstrations, and sit-ins with CORE. There is a story of one of the sit-ins where the white manager at the lunch counter held a gun to my grandmother’s head when she refused to leave and insisted on being served. Tee Jean made her own waves in the movement, too. She was participating in a sit-in at a lunch counter in New Orleans. The manager called the police to have them arrested. She went limp in her chair, in accordance with their training on civil disobedience. Instead of removing her from the chair, police picked up the chair and carried her out in it! The photo of her being carried out made international headlines. In today’s terms we’d say she “went viral.” It was a moment that showed the world some of the realities of segregation in the south, and the resilience and strength of those fighting against it.

I was Mama Oretha’s plus-one to every kind of civic, political, nonprofit meeting, or other community gathering imaginable.

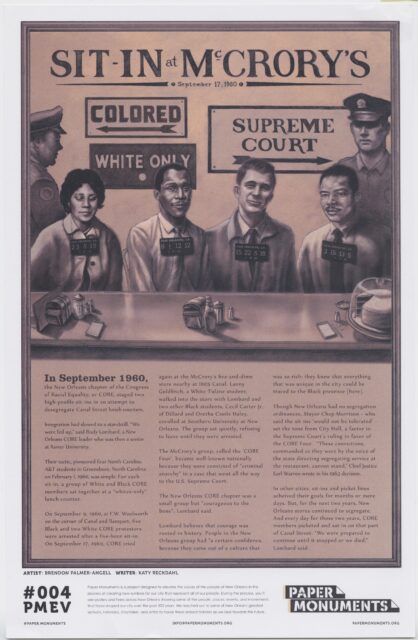

Mama Oretha and Tee Jean continued to work with CORE and joined the Freedom Riders. Their home at 917-19 North Tonti Street would become the New Orleans destination for the Freedom Rides. Their lunch counter sit-ins became the basis for one of the biggest civil rights case wins of the movement, Lombard v. Louisiana. While students, Mama Oretha and Rudy Lombard, along with two others, Cecil Carter and Sydney Goldfinch (who was white), sat in at the Woolworth lunch counter on September 17, 1960. That protest and case would strike a blow to Jim Crow and pave the way for integration in public places.

As a child, I was aware that my grandmother and great aunt, along with my grandfather Richard Haley and other family members, had made significant contributions to the community and society. Starting at the age of four, until she fell ill when I was eight, I was Mama Oretha’s plus-one to every kind of civic, political, nonprofit meeting, or other community gathering imaginable. I mean she brought me with her everywhere she went! It was during these outings that I not only learned about her continuing work for the betterment of Black people, but also the tremendous respect she had earned among so many. One of the most memorable parts of these outings was a game we’d play where I would review the lyrics of the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” for errors. Typically, many of the meetings I would attend with her began with everyone standing and singing all three stanzas, and they’d be printed on the meeting programs. What I learned for the future during these outings was her fierce love for Black people, and the enormous amount of work that still was needed to lift Black people from systems of oppression.

Castle Haley’s participation in the McCrory’s lunch counter sit-in was memorialized in the Paper Monuments public art and history project. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

These experiences set in me a deep sense of responsibility to use my life to help lift Black people, and a strong feeling of accountability to honor her work and legacy. I really felt that awareness heightened exponentially when a documentary called A House Divided, about New Orleans’s contributions to the civil rights movement, was shown at my elementary school, Audubon Montessori. As we watched, I learned so much more detail about the movement, and not only the involvement of my grandmother, great aunt, and grandfather, but also that so many of my extended family members were integral to the fight. Don Hubbard, Lolis Elie, Rudy Lombard, and Dodie Smith-Simmons were all familiar faces to me, and they were featured in this documentary. It was a pivotal moment in my understanding of who I had come from and in whose company I had been nurtured.

One of my favorite stories of my time with Mama Oretha was one Christmas when she took me out with her shopping for gifts for other people. She often shared with me how she thought my parents spent too much money on Christmas, as I was an only child at the time and she believed I didn’t need so much. Well, of course, before we left Lakeside Mall, I asked her to buy me a set of fancy green marbles that were in the display case at Goudchaux’s department store. She looked at me with “that look” and said, “If I buy you this, this is your Christmas present!” I agreed because at that moment, I wanted those marbles and I didn’t really think she would follow through with that being my only gift from her. Two weeks later, Christmas came, and there was indeed no other gift for me! I was initially shocked and a little hurt (HA!) but quickly understood the lesson. It was a Christmas I’ll never forget, because I learned such valuable lessons about keeping my word and understanding and accepting the consequences and tradeoffs that life would present to me based on my conscious choices.

One of the other most valuable lessons that I learned from my grandmother and my great-aunt is that we all can play multiple roles and serve various purposes in our people’s liberation. This lesson was taught by example as they both transitioned in their work as freedom-fighters from sit-ins at lunch counters and marches in the streets to other forms of civic and community leadership. Mama Oretha became even more of a force in politics, serving as campaign manager for Dorothy Mae Taylor, the first African American women to be elected to the Louisiana House of Representatives and the New Orleans City Council, as well as for Gail Glapion’s election to the Orleans Parish School Board. Mama Oretha also went to work in the fields of public health and education. Throughout the ’80s she served as deputy administrator of Charity Hospital. Her appointment to this position, by then Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards, was both historic and serendipitous. She was the first Black woman to hold that position, and even more extraordinarily, she had worked on the court case of her grandmother Callie Castle that integrated Charity Hospital years earlier.

Mama Oretha wasn’t done. She also forged her way in education both at the foundational level and higher education. In 1980, she founded The Learning Workshop, a preschool missioned to educate, inspire, and lift Black children, following the African proverb “Children are the reward of life.” (My parents went on to operate the school, located at 2016 Painters Street, until Hurricane Katrina hit in 2005). What stands out in the hearts and minds of many New Orleanians around my age when they hear the name Oretha Castle Haley isn’t just her legacy of fighting for civil rights but this institution that she built for the education and cultural development of young Black minds, including mine.

Fully recognizing that education is a journey, while building the Learning Workshop she simultaneously took a position in higher education with LSU School of Medicine, assisting minority students with gaining access to medical school. In 1973, she also helped found and lead the New Orleans Sickle Cell Anemia Foundation in efforts to combat the disease that disproportionately affects Black people. My great aunt took much less of a public interfacing role in the post–civil rights era by going to work for Charity Hospital and providing some of the best quality care for New Orleans citizens through her work in public health.

The author, Blair Dottin-Haley, at a sign marking the street named for his grandmother. Photo by Lavonte Lucas.

These extraordinary and brilliant women instilled in me that working hard for our people is a lifetime mission—that no matter where I found myself in the world, I could do something to lift, celebrate, and empower Black people. That is the greatest lesson I was taught from the blessing of sharing time and space with them both. There’s always more to learn, to know, to understand, to celebrate, and certainly more to fight. They both transitioned from the physical world prematurely. We lost Mama Oretha in 1987, when she was just forty-eight years old, after a short fight with ovarian cancer, and then Tee Jean just ten years later. Losing them so early in my life heightened my sense of responsibility and accountability to their legacy. I am the only member of this generation of my family to have shared space and time with them.

It has been one of this life’s greatest gifts and responsibilities to be one of those asked to stand and represent who they were. I’ve had the opportunity on many occasions, as street and school names have been changed and as programs of speech, song, and dance have been performed in honor of their contributions. But their legacies live and thrive and shine through all of us! My father and uncles, Michael, Martin, Okyeame, and Sundiata, me, my brothers Cassell and Malik, my cousins Nia, Kai, Simone, Sundiata Jr., Mama Oretha’s children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, and Tee Jean’s great-nieces and -nephews are excelling in every facet of life imaginable, from medicine to media to dance and everything in between. As living examples of their determination to love and lift Black people, we will ensure that their names won’t only grace street signs and building marquees, but be known for the fierce and bright beacons of strength, conviction, character, and determination that they were.

Blair Dottin-Haley is a New Orleans native, veteran vocal performer, and co-founder with his husband Brandon of the #BLAIRISMS lifestyle brand, which uses apparel to speak truth to power, celebrate Blackness and queer identities, and shine a light on the breadth and range of Black culture. Blair has worked in politics for both the Texas and Louisiana legislatures, and in the field of education as a classroom teacher, media specialist, and national program operations manager for a college access non-profit.