The Many Lives of Marie Baron

A French orphan survived captivity in two countries to give an early testimonial of women’s experiences in colonial Louisiana

Published: May 31, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

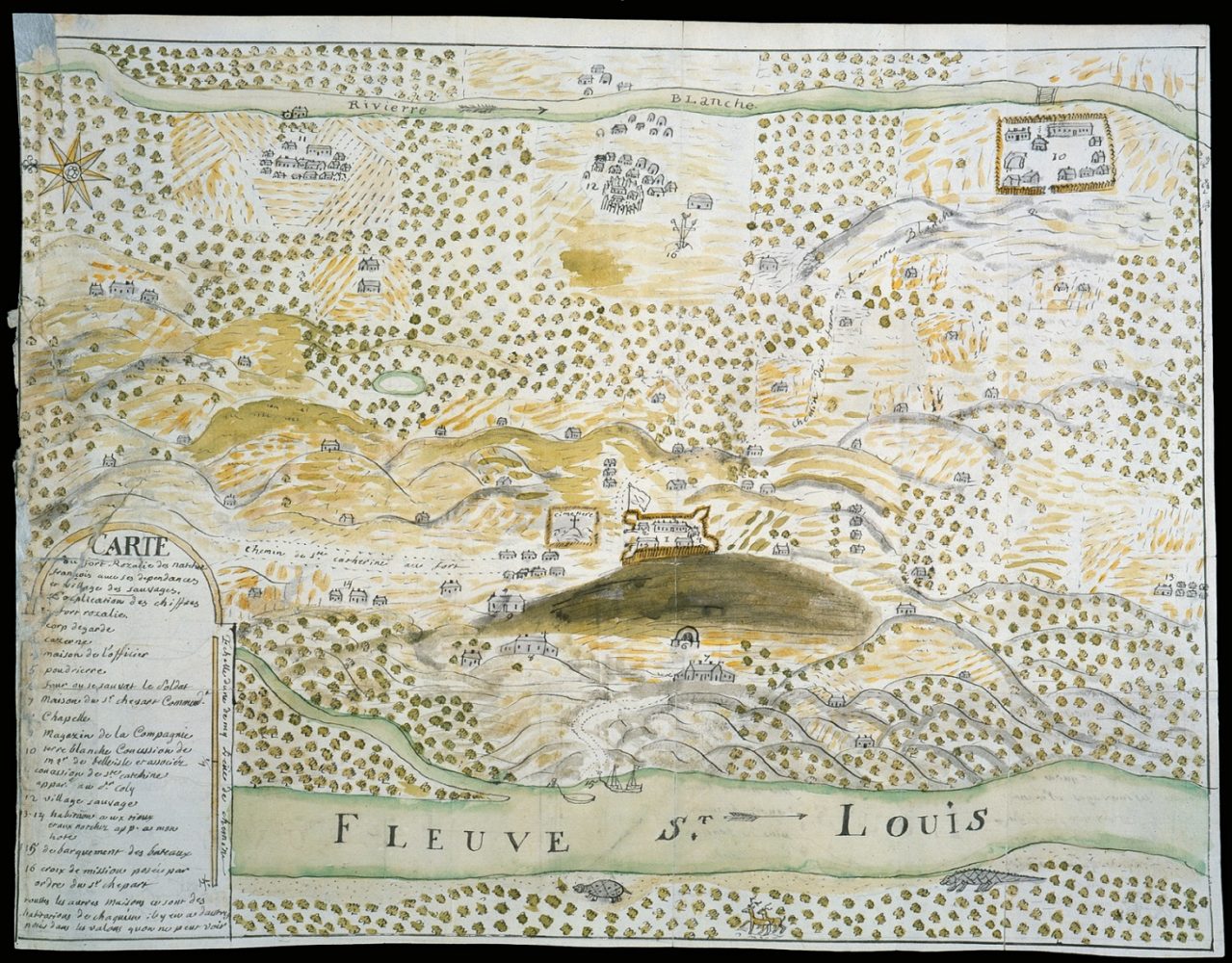

Newberry Library, vault oversize Ayer MS 257 map 9

Map of Natchez and surroundings by Marie Baron’s second husband, Jean-François Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, ca. 1750.

Baron first crossed an ocean because of transportation, a term for the practice of shipping convicts across the Atlantic to the colonies. The English had engaged in transportation for a century when, in 1719, the French began experimenting with what they officially termed “forced deportation” to the New World. The French practice was new in two essential ways. While the English transported convicts for a fixed period, usually seven years, the French deported people in perpetuity. Most transported Englishwomen had been convicted of theft, while deported Frenchwomen were publicly pronounced “prostitutes,” even though none of them had been officially convicted. Most had had no form of due process at all.

When New Orleans was founded in 1718, French officials decided that the new colony required both enslaved Africans and Frenchwomen—very quickly and in that order. Drawing on their extensive prior experience with the slave trade, the French managed to dock ships bearing African captives destined to labor in Louisiana by May 1719. But importing women intended to serve as prospective brides for the colony’s overwhelmingly male populace was another matter.

Marguerite Pancatalin, the enterprising warden of the notorious Parisian women’s prison, the Salpêtrière, decided to get ahead of the game. By November 1718, Pancatalin had drawn up a master list of some two hundred women whom she pronounced “Bonnes pour les îles”—“fit for the islands.” (Despite not being an island, in the early French colonial period Louisiana was often grouped in with French possessions in the Caribbean.) Within a year, about 125 of these women had left Paris, shackled at the waist, and had been taken to one of the only two ships ever to transport female convicts to a French colony. The women crossed the Atlantic in the ships’ holds and in chains.

Slavery was the only model for forced human transportation the French could imagine, with the key difference that African slaves had real monetary value for the French, so ships bound for New Orleans from Africa had a doctor on board for the express purpose of checking each captive’s health every day and making sure that they were given sufficient nourishment. No one assigned any such value to the women on board.

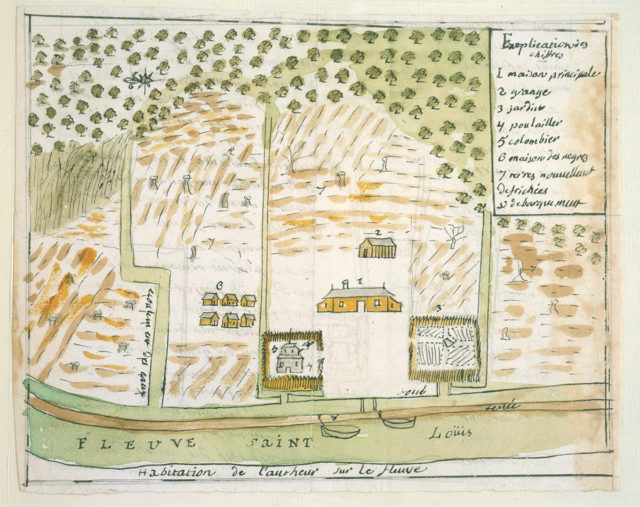

Baron and Dumont De Montigny’s plantation along the Mississippi River, then also known as the St. Louis River. Newberry Library, vault oversize Ayer MS 257 map 8

Marie Baron’s early years were a cycle of poverty and death. By her seventh birthday, she had lost both her parents and her only two siblings. When her father died in 1710, the family was penniless, and members of a Christian lay charity, the Confrérie de la Charité, covered the tiny sum necessary for a burial.

An illiterate, impoverished orphan, Baron endured a decade of sudden climate shifts that devastated Beauce, her home region and the breadbasket of France. Winters were so cruel and harvests so disastrous that the cost of basic foodstuffs tripled. In 1709–1710, the year of her father’s death, the mortality rate in France was forty percent higher than normal. Thousands of starving villagers roamed the countryside in search of food. Cities began locking their gates against ever larger mobs; the desperate paupers would then try to dig their way under the walls. Amidst all the mayhem, Baron somehow ended up in the largest orphanage in France, Paris’ Hôtel-Dieu. There she met a young Parisian orphan just her age, Anne-Catherine Crétin. That encounter changed the course of her life.

On June 9, 1719, the two sixteen-year-olds visited what must have seemed like paradise: a well-stocked emporium run by a ribbon merchant named Sergé on Paris’ premier shopping street, the Rue Saint-Honoré. Sergé called in the police, alleging that Crétin and Baron had stolen “a piece of ribbon shot through with gold and silver.” When nothing was found on them, Sergé added that they had “adroitly” slipped it to a third young woman, who had run away. Their arresting officer, Huron, realized that this hardly constituted proof, and so took it upon himself to add to his report that both had been known to the police as prostitutes and thieves for some time—even though Baron, as Huron well knew, had no prior arrest record.

Baron, with no one to advocate for her release, left Paris in chains.

All officers of the Parisian police were aware that warden Pancatalin wanted to fill her quota of women “fit for the islands.” They were likely also aware that orphans were considered ideal candidates for deportation, without parents to protest if they were sent away. Without further investigation, officer Huron had the two friends transferred to the Salpêtrière on June 26, 1719—the day before Philippe d’Orléans, the Regent governing France, approved Pancatalin’s master list and legalized the forced deportation of women. On the list, Crétin and Baron appear as numbers 69 and 70 and are labeled “public prostitutes.”

Crétin had relatives in Paris, who quickly and successfully begged for her to be released into their care. On October 6, Baron, with no one to advocate for her release, left Paris in chains. The following February 27, she landed in the port of Mobile, then the Louisiana colony’s principal port.

Baron soon married Jean Roussin, a young French farmer. It’s unknown exactly when; no records have survived for the first marriages made by women who traveled on La Mutine. The earliest sacramental register for Saint Louis Church begins on July 1, 1720, five months after the ship had reached the colony. Whether the two met and married in Mobile or elsewhere in the colony is also unknown, but by 1722 Baron and Roussin appear in a colonial census as a married couple living in Natchez, a settlement some 240 miles upriver from New Orleans. There, they created a prosperous establishment on two arpents, nearly two acres of land, just outside the enclosure of Fort Rosalie, the French military base at Natchez. They raised two sons; they cultivated tobacco. An early account describes Baron as “very wealthy”: Marie had come a long way from her childhood. Then came 1729.

French relations with the Natchez Indians, who far outnumbered the tiny French garrison stationed at Fort Rosalie, had started off peaceably but deteriorated rapidly over the previous year, after a new French commander misappropriated Natchez land. In retaliation, on November 28, 1729, the Natchez attacked Fort Rosalie, killing 144 men, 36 women, and 56 children. Baron watched her husband and eldest son become part of that tally. Baron herself was taken captive, along with a handful of French women and children and all the enslaved Africans on the post. Then began roughly four months of negotiations between the captors and the French for the captives’ release.

Contemporary evidence, including the first accounts of the attack and correspondence among French officials, makes one thing clear: both sides in the negotiations saw the captured slaves as valuable property but the women as hardly worth bothering about. The most reliable contemporary chronicler, Jean-François Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, (whom Baron later married) put it this way: “The negro slaves became free, you might say, and the French women . . . were reduced to the utmost extremes of slavery.”

In January 1730, the Choctaws, allies of the French, broke into the Natchez fort and seized some of the captives, including Baron. They did not free them but instead demanded a higher ransom. By the time the women had been exchanged for guns and powder and returned to New Orleans in March 1730, a Jesuit missionary described those women he called newly freed slaves as clad in little more than rags. To buy clothing, each was given a small credit at the city’s storehouse, money they were soon forced to repay.

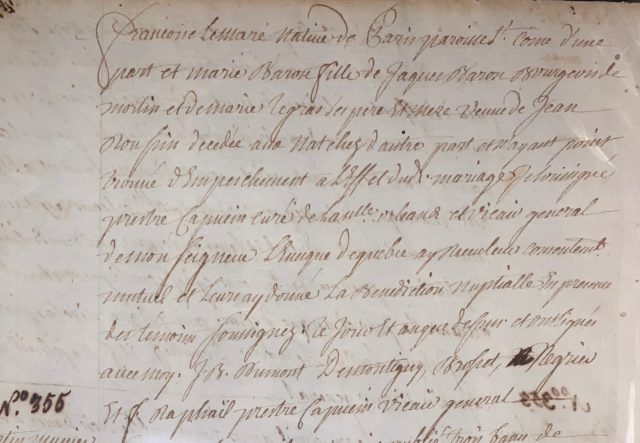

Baron was among those who quickly made a new start: on April 19, 1730, in New Orleans’ Saint Louis Church, she married Dumont de Montigny, a French officer and the son of a prominent lawyer for the Parisian Parlement. The couple had known each other for some time; when Dumont de Montigny was stationed at Natchez, he had boarded with Baron and her husband, and they had become close friends. They soon had two children of their own, as well as a prosperous farm.

Marriage record of Marie Baron and Jean-François Benjamin Dumont de Montigny, 1730. Office of Archives and Records, Archdiocese of New Orleans

Today Baron’s second husband is best known as the most prolific early historian of French Louisiana. Dumont de Montigny composed voluminous memoirs, some of which formed the basis for the 1753 Historical Memoirs of Louisiana. His memoirs have always been seen as one of the definitive early accounts of the Natchez uprising, despite the fact that Dumont de Montigny himself openly admitted he was nowhere near the fort in November 1729. Only recently have researchers pointed out that his wife was among the few eyewitnesses who lived through every major milestone of 1729 and 1730 in the French colony. Fortunately, Baron’s testimony was recorded in her husband’s history of Louisiana.

Baron and Dumont de Montigny remained in Louisiana until June 12, 1737, when they and their children sailed to France, taking with them provisions for the voyage: a cow, a calf, three dozen chickens, and two dozen turkeys. This is the only recorded instance of a deported convict woman’s permanent return to the country that had sent her away in chains. They reached Le Mesnil-Thomas, Baron’s birthplace, in September 1737, where Baron was reunited with her favorite cousin.

The woman who had made her first ocean crossing chained in the hold now had the privilege of a seat at the captain’s table.

The family then took up residence in Port-Louis, a port city on the Brittany coast, where Dumont de Montigny began work on his memoirs. Their daughter Marie-Anne married in 1748. Their son Jean-François continued the family’s ocean-going tradition: in 1749, he sailed to Senegal and later traveled to Mauritius. Then, in 1754, the couple went to sea again, destined for the Indian Ocean colony of Île Bourbon (today Réunion). Next to the name of passenger 171, Dumont de Montigny, the ship’s manifest recorded that he was “à la table avec sa femme.” The woman who had made her first ocean crossing chained in the hold now had the privilege of a seat at the captain’s table.

The pair later traveled to Mauritius and then in 1755 continued on to Pondicherry, which would soon be caught up in the French and Indian War. They survived the sack of the French settlement by British forces in 1757. Dumont de Montigny died in India in 1760, leaving an estate of nearly 6,500 French pounds. The couple had turned their life in Louisiana, the poorest French colony, into a rather spectacular financial success.

No record survives of Baron’s death. Her story lives on in Dumont de Montigny’s writings, which recorded not only her eyewitness testimony about the events at Natchez but also the horrendous conditions that transported women endured in a colony that was in no way prepared for their arrival. Her account addresses a substantial gap in the written record, as French officials in Louisiana rarely mentioned the deported women in their correspondence with their counterparts back in France. No one even bothered to note the exact number of those who survived the voyage. Marie Baron’s testimony is indeed the only contemporary account of the deportation of women to what may be the least charted of this country’s eighteenth-century frontiers. We could think of her as the original historian of women’s lives in colonial Louisiana.

Joan DeJean has been Trustee Professor at the University of Pennsylvania since 1988. She previously taught at Yale and at Princeton. She is the author of eleven books on French literature, history, and material culture of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, including most recently The Queen’s Embroiderer: A True Story of Lovers, Swindlers, and the First Stock Market Crisis (2018) and The Invention of Paris: Making the City Modern (2014). She is currently at work on a book about the lives of the women deported to Louisiana in 1719.