Winter 2015

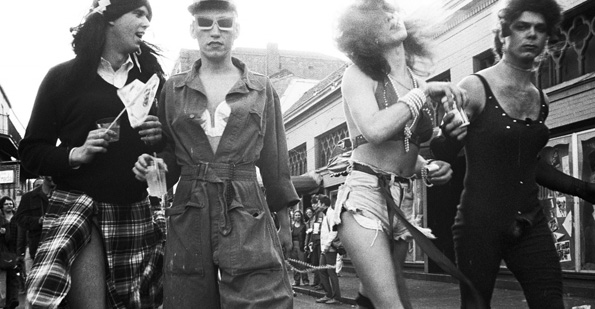

Mardi Gras 1979

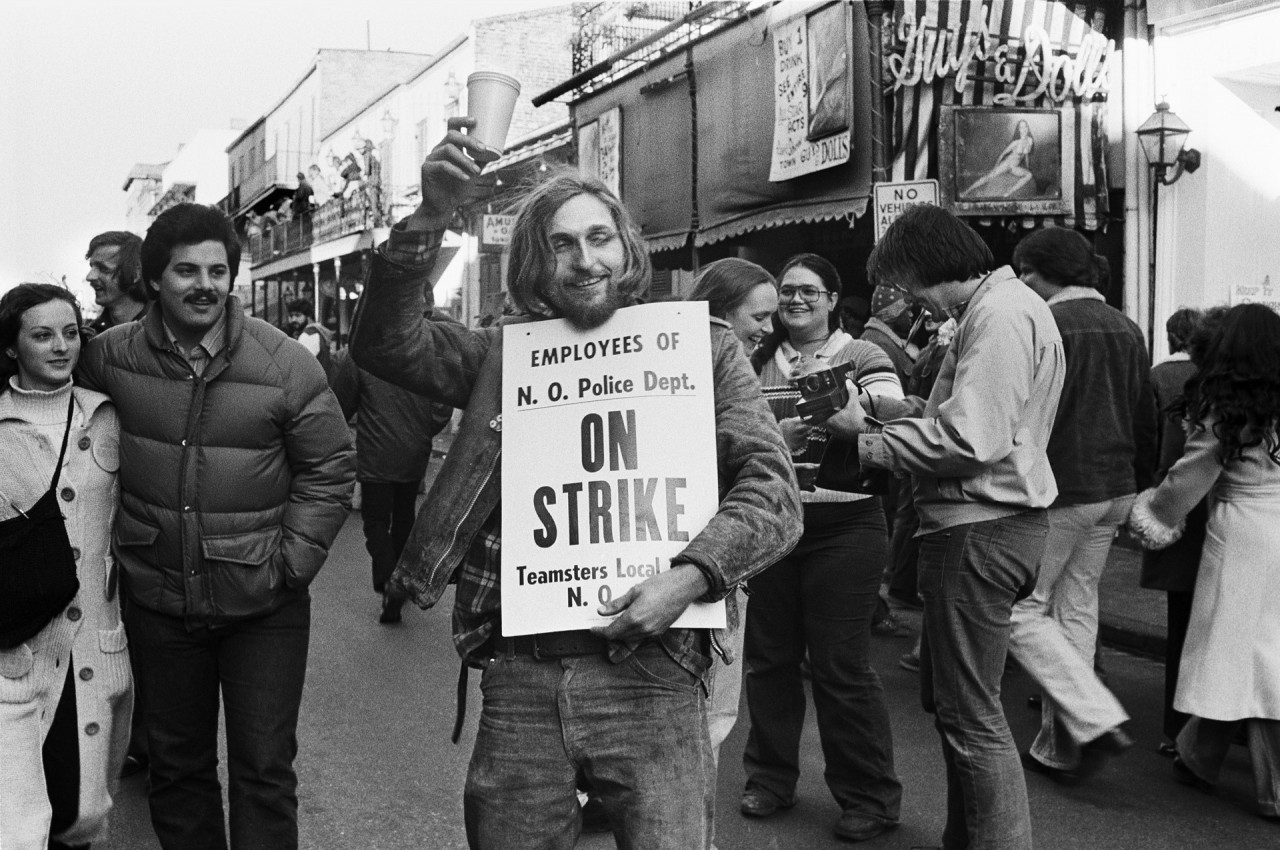

Photographer Rob McClaran documented Mardi Gras the year of the 1979 police strike

Published: December 14, 2015

Last Updated: January 3, 2019

Photo by Robbie McClaran

In that last year of a tumultuous decade that witnessed the end of the Vietnam War, Watergate, runaway inflation, gas shortages and dramatically shifting societal standards, New Orleans police went on strike in the weeks preceding the devil-may-care season of wild abandon. By holding Carnival hostage, the Teamsters’ Union put intense pressure upon Mayor Ernest “Dutch” Morial to meet the police department’s demands before the first bead-loaded floats were hitched to tractors. Morial refused to cave in and opted to cancel all parades. Yet, for New Orleanians, the show would go on in spite of the labor dispute. National Guardsmen were called in to patrol the French Quarter and tourists largely stayed home, but locals slipped into costumes, donned masks and took to the streets of the Vieux Carré for a party that many nostalgically remember as the best Mardi Gras of their lives.

Robbie McClaran, then a 23-year-old recent art graduate newly arrived to New Orleans from Rochester, New York, was disappointed at first by the turn of events at this, his first Mardi Gras. Nonetheless, he had his camera ready for whatever might happen. The resulting images have largely been kept under wraps in the decades since, but the Portland-based photographer’s prints are on display at Fee and Art’s Revival Studio, a gallery combined with a hair salon at 834 Chartres Street, through February 14, 2016, as part of PhotoNOLA, an annual celebration of photography in New Orleans coordinated by the New Orleans Photo Alliance in partnership with museums, galleries and alternative venues citywide. McClaran will speak about his work on Saturday, December 12, at noon at the gallery.

Louisiana Cultural Vistas magazine asked the photographer to share his memories and explain how this body of work came to be.

• • • • •

Well, it’s a little bit of a story, one that might sound unbelievable. I had finished two years of art school in Rochester, at the Visual Studies Workshop and after school I had done what so many college students do. I took a backpack and headed to Europe and bounced around until I more or less ran out of money and came home essentially broke. I got back to Rochester where I was basically sleeping on a couch in an unheated apartment—a place nobody wants to be in winter—so I knew I didn’t want to stay there, but I wasn’t quite sure where I wanted to go. Then one night I had a dream where I was walking through the French Quarter, and I woke up the next morning and said, “I’m going to New Orleans.” And the day after that I left. I arrived in New Orleans only having been there one other time for a very brief visit, but I loved it. I managed to find the original hotel that I’d stayed at on my very first visit, the Hotel Lafayette, which in those days was a real flophouse. It’s since been renovated and they kicked all the bums out. It’s quite an upscale place now. I had a little bit of money, enough to get by for a few days, but I managed to get a job pretty quick for an audiovisual company that would provide slide projectors and other equipment for big conventions in places like the Superdome. I spent a lot of time taking down cords. I found an apartment on Esplanade, in a slave quarters. And there I was.It was the first time I’d ever been to Mardi Gras and it was the last time I was at Mardi Gras, so I have nothing else to compare it to. It was quite a feast for my eyes.

I came to New Orleans to largely experience it, to see if I liked it, and I fell in love with it. It was a wonderful place to make photographs. I spent essentially all my waking hours when I wasn’t working out on the streets taking pictures—as much as my paltry budget would allow. Later on I got a waiter job in Metairie. I didn’t have a car so I had to ride a bus and it would take me forever to get out there.

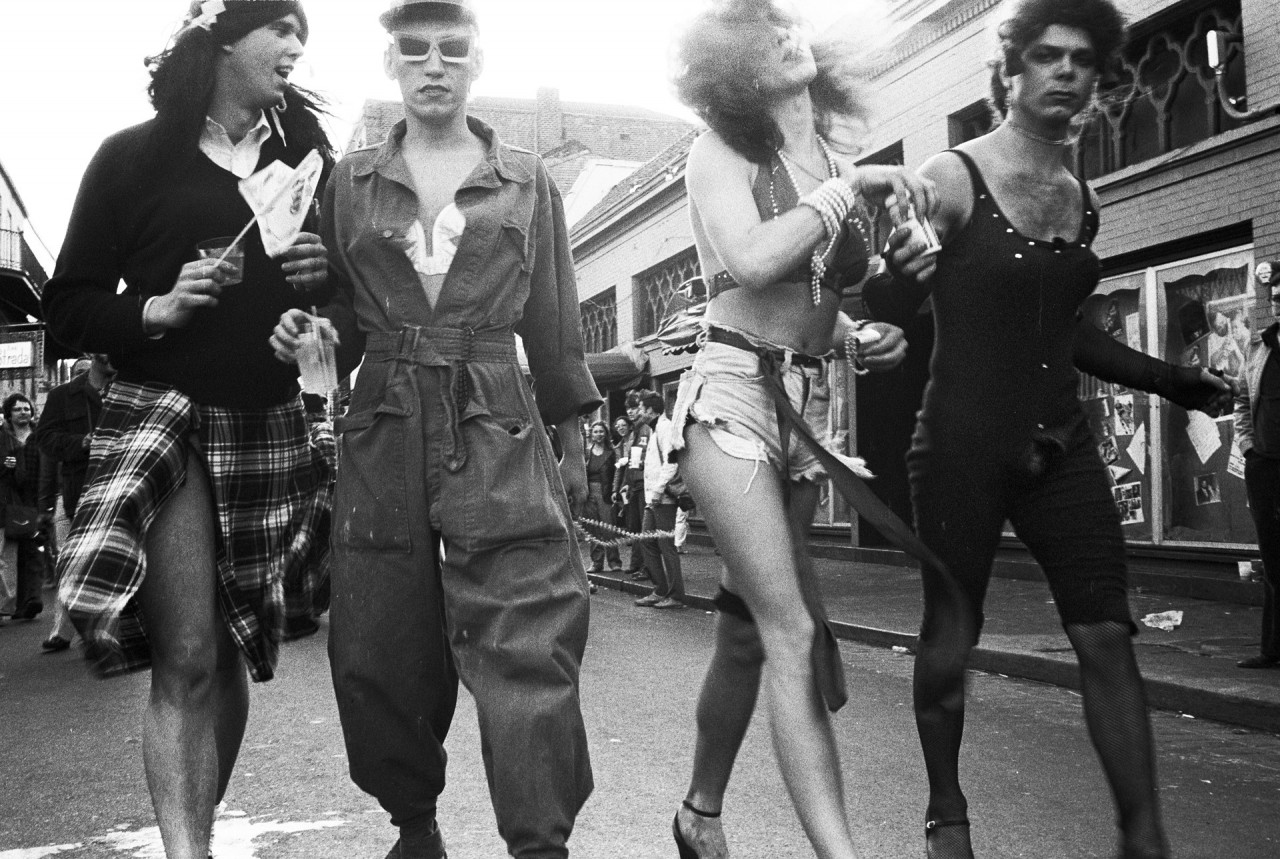

I wasn’t even in New Orleans a complete year. I think it was seven months, but Mardi Gras rolled around and the police went on strike and I was thinking, “Damn!” But it ended up being recorded in the history books as a fabulous Mardi Gras. As I recall, a lot of the big parades were cancelled, or they moved some of them to the suburbs. They called in the National Guard to sort of keep the peace, but the National Guard was not so interested in enforcing the law, they were just trying to keep people from hurting each other. So all manner of decadence was on full display. It was the first time I’d ever been to Mardi Gras and it was the last time I was at Mardi Gras, so I have nothing else to compare it to. It was quite a feast for my eyes.

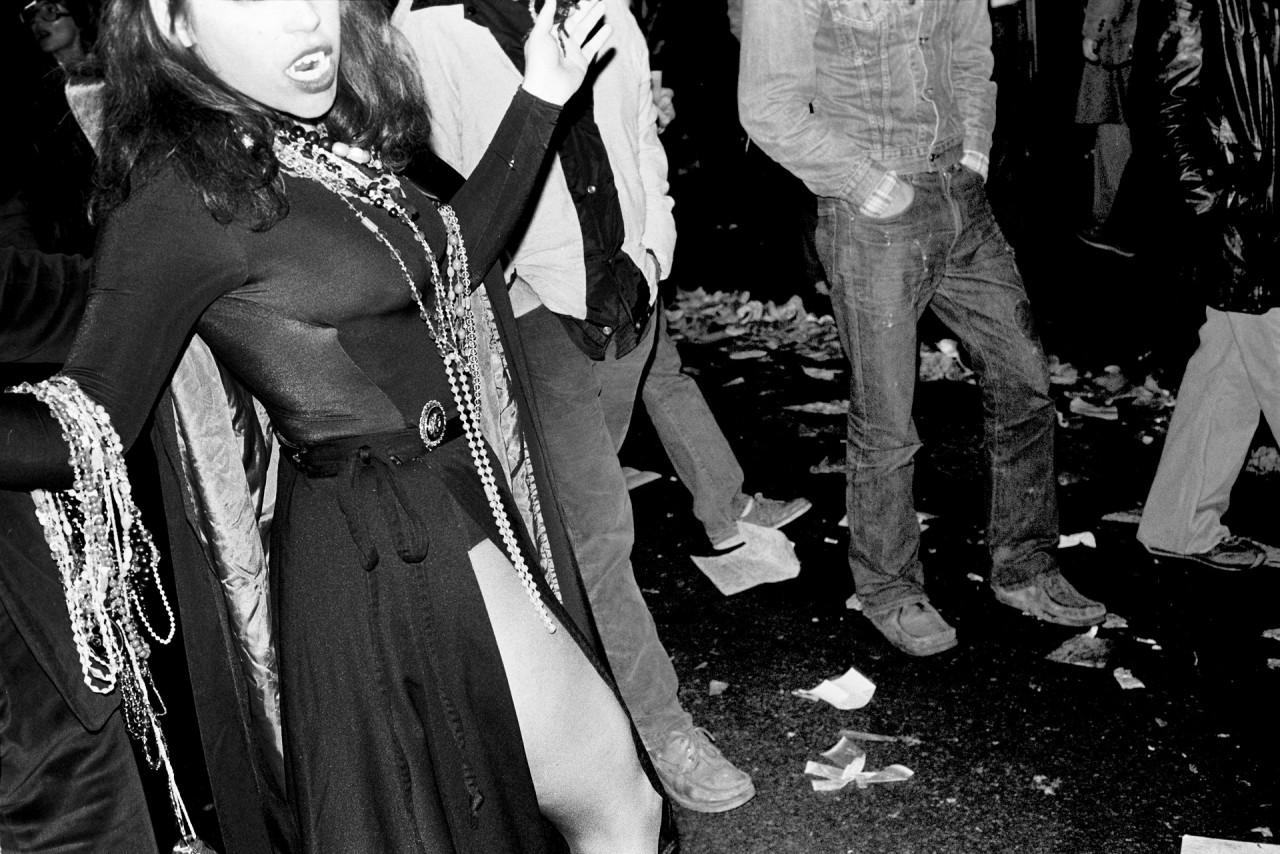

Everyone was just giddy, just happy and celebratory and in full party mode. I got the sense that they thought, “You can cancel Mardi Gras, but you can’t stop us from partying!” There were probably fewer tourists and more locals. Folks were dressed up, it was just pure revelry.

It was at at a time just a few years before AIDS arrived. It was the first time I had lived in a community that was so accepting of out gay culture. It was cool for me to see gay men out reveling openly in the streets. That’s not something I had ever seen before. I was like, “Wow, this is incredible!”

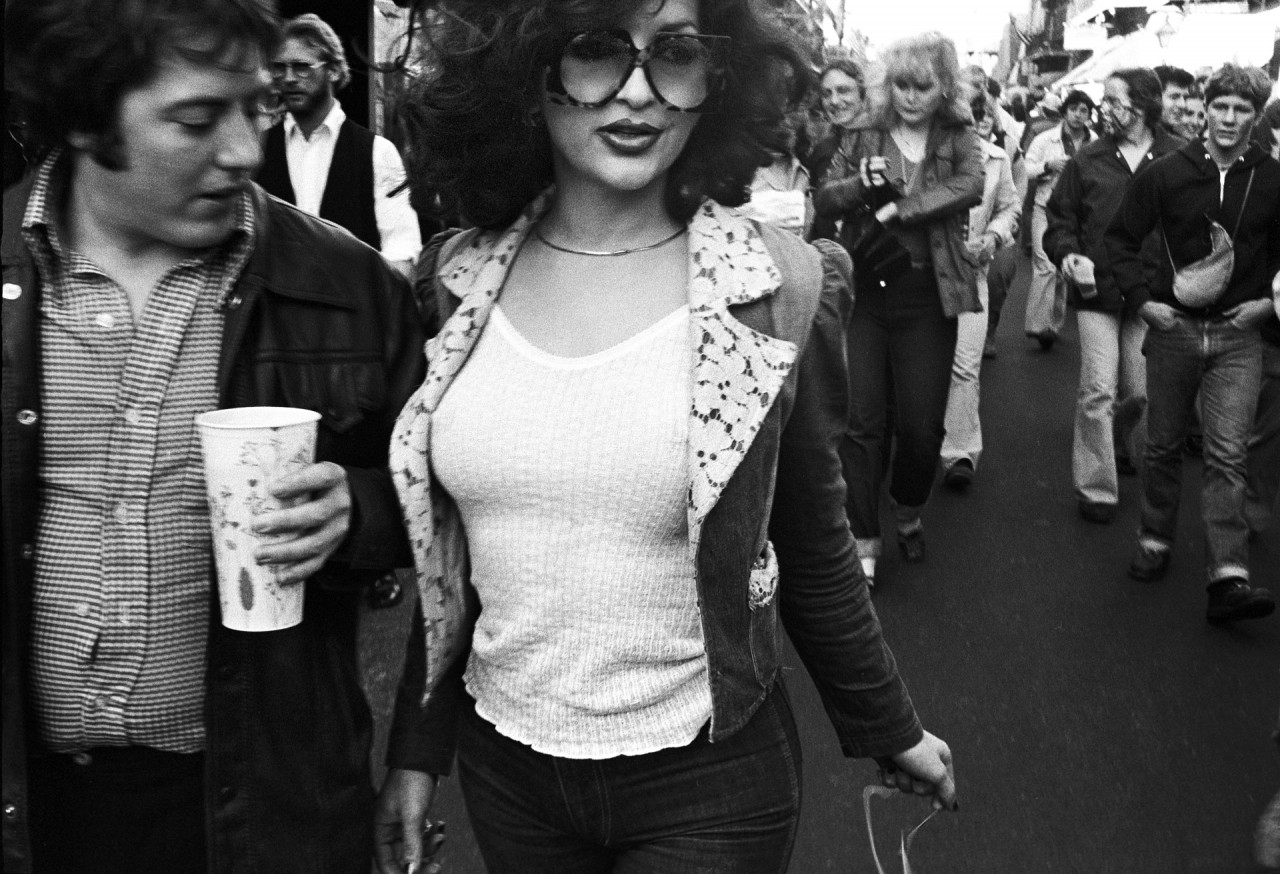

For me, it was visual overload, overstimulation. I was taking pictures of everything but also fully participating. I was having a few drinks here and there myself, and I was encouraging folks to perform for the camera. These are not purist photojournalism. I was stopping and talking to people and asking them to pose for the camera. Some of it was pure documentary photography, but with others I was engaging with the subjects.

For me it was visual overload, overstimulation. I was taking pictures of everything but also fully participating.

I kept these photographs stored away. I showed them to a handful of friends, just a few tiny 3×5 work prints and just a very, very few enlargements. Part of the reason was there was such a high level of sexual content and public nudity and all, and my work had never really been about that. I was young and trying to start my career and to be perfectly honest I didn’t know how people would react to them if I showed them. They might think I was some kind of crazy man or maybe that I was perverted. [Laughter.] I was trying to be taken serious as a young professional and I wasn’t sure these pictures were the ones that I wanted to represent me. So for the most part I put them away until just a few years ago.

A couple things happened about two to three years ago. I saw a body of work by a photographer named Henry Horenstein who had photographed the bars and honky tonks in Nashville in the mid-1970s. Around that same time I also saw Bill Yates‘ work documenting the Sweetheart Roller Rink that’s currently showing at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art [through Jan. 17, 2016]. These were also photographed in the 1970s. One of the things I realized when I went back through these negatives was that here was my time capsule of the ’70s — the fashions, the attitudes and the overall scene. One of the things that gave me a big chuckle are all the cameras that you see people using in these photographs. In one of the pictures there’s a little Brownie camera, then there’s a Polaroid. You see all these cameras that noboby’s using anymore.

The New Orleans Photo Alliance recently had a call for submissions for a group show with the theme “Masquerade.” It was fairly open, but it was people in masks, people dressed up, that kind of thing. On a lark, I sent in five pictures and one of them got selected for the show, so I thought, “Well okay, cool!” I went in the darkroom, printed it up, got it matted and framed, and I started thinking I should really get into that body of work from 1979, and so I spent several days going through the negatives, making selections, and doing high-res film scans. I put together a selection of images, showed them to a few folks and decided to put them up on my website. Then this last summer I got notice that PhotoNOLA was putting out a call for exhibitions, so I sent these pictures in, not really expecting much. By a certain date I didn’t hear anything. You get thick skinned in this business, you’re used to rejections, so I didn’t take it personally. Then in mid-September I got a call from Jen Shaw, PhotoNOLA’s director, who put me together with Arthur Severio of Fee and Art’s. She said Arthur was interested in showing the work and if I wanted to do it. I said, “Absolutely.”

I would love to return to another Mardi Gras. I’ve been trying to get back to New Orleans ever since I left. When I left New Orleans it was not because I didn’t love living there, I absolutely loved living there. I left because all I had with me when I arrived was just a backpack and a camera bag. I didn’t have any of my books, or my records, or any of my stuff, none of my darkroom equipment or any of that. I had a book project that I wanted to do, so I left New Orleans with the idea that I would come back after going to Rochester for six months to finish this book project and then gather all my things and load it up in a truck and move back to New Orleans and live there the rest of my life. Well, as most people know, life doesn’t always turn out the way you planned. One thing led to another, one fork in the road led me down a different path, and here I am almost 40 years later in Portland, Oregon, and I’m still trying to get back to New Orleans. I have been back to visit on several occasions and for many years I had this fantasy that I would come to a place of financial security that would allow me to spend my winters in New Orleans and my summers in Portland. Yeah man, I’m still trying to get back down there. The financial security part of the plan hasn’t quit worked out the way I had planned. My winter place there, it may be somebody’s couch.

• • • • •

Rob McClaran’s work as an editorial photographer has appeared in diverse publications such as The New York Times Magazine, Time, Smithsonian, Sports Illustrated, Esquire, Rolling Stone, Runner’s World, Bloomberg and Forbes.

The entire collection of prints from McClaran’s controversial book, Angry White Men, is in the permanent collection of the University of Oregon, Special Collections Library. His fine art work is in several private and public collections, including the Portland Art Museum and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

View more of McClaran’s photographs at his website: mcclaran.com.