Memories of Nonc Tom’s

A photographer’s ’70s sojourn in Basile

Published: August 30, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Photos by Ron Stanford

The author’s wife, Fay, with a cat at Nonc Tom’s.

Two years earlier, I hired Dewey Balfa and his band to drive to Grinnell, Iowa, in the dead of February to perform at our college folk festival. The Balfa Brothers and Nathan Abshire were a huge hit with my fellow students, who to this day nostalgically remember their introduction to Cajun music. One night, at a drunken dorm room party, Dewey, with his characteristic emotional delivery, invited me to move to Louisiana one day to help him preserve his beloved French music.

Dewey Balfa (right) jamming in our living room with Marc Savoy (left) and Nathan Abshire.

Two years later, Fay and I, with our fresh liberal arts degrees, had run aground in my parents’ basement in suburban Washington, DC. Then I remembered Dewey’s invitation, found his phone number, and within a couple weeks Fay and I were on our way to Basile. Aside from getting out of Dodge, our mission was to learn all we could about the different kinds of French Louisiana music and produce a record with articles and photographs. We knew nothing much about the subject other than hearing the Balfa Brothers play.

After three months of Fay’s substitute teaching and my entry-level construction jobs, our project was going nowhere. But with the timely help of a much hoped-for Youthgrant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, we were instantly able to work full-time on our musical survey. In the evenings we scouted for bands in the dance halls, many within just a few miles of our house. If a musician piqued our interest we’d introduce ourselves and the next day drive to the musician’s home for an interview and some photos. Then we’d return to Nonc Tom’s to transcribe the tapes, write liner notes, and make prints in the darkroom. Just as we were leaving Basile in September of 1974, Fay and I released a compilation album of the full range of Cajun and zydeco music we’d encountered (J’Étais au Bal: Music from French Louisiana. Swallow Records, Ville Platte, LA, 1974).

Our first and only Louisiana snowstorm.

We heard all the gossip. Well, maybe not all the gossip. As we became citizens of Basile, we’d hear bits of community wisdom about Nonc Tom. He was so frugal that when he’d buy his black Ford sedan every few years, he’d order it without a back seat—just to save money. I thought it was such a great story that I recounted it in my 2019 book, Big French Dance: Cajun and Zydeco Music 1972–1974, which featured pictures of musicians and dancers but also included several shots I had snapped around that photogenic old house.

Last year a reader of my book wrote and asked me if I had any more pictures of the place. It was Mona Young Redlich of Eunice, Louisiana, great-granddaughter of Nonc Tom. She was preparing a big eighty-ninth birthday celebration for her father, John Austin Young—Nonc Tom’s grandson, who moved to the old place in 1976 with Mona’s mother, Lula.

John Austin Young, the current resident of the property, has researched the history of Nonc Tom’s, and in 1991 published a book about his family, The Lejeunes of Acadia and the Youngs of Southwest Louisiana. Mona is planning a revised edition. Photo by Mona Young Redlich.

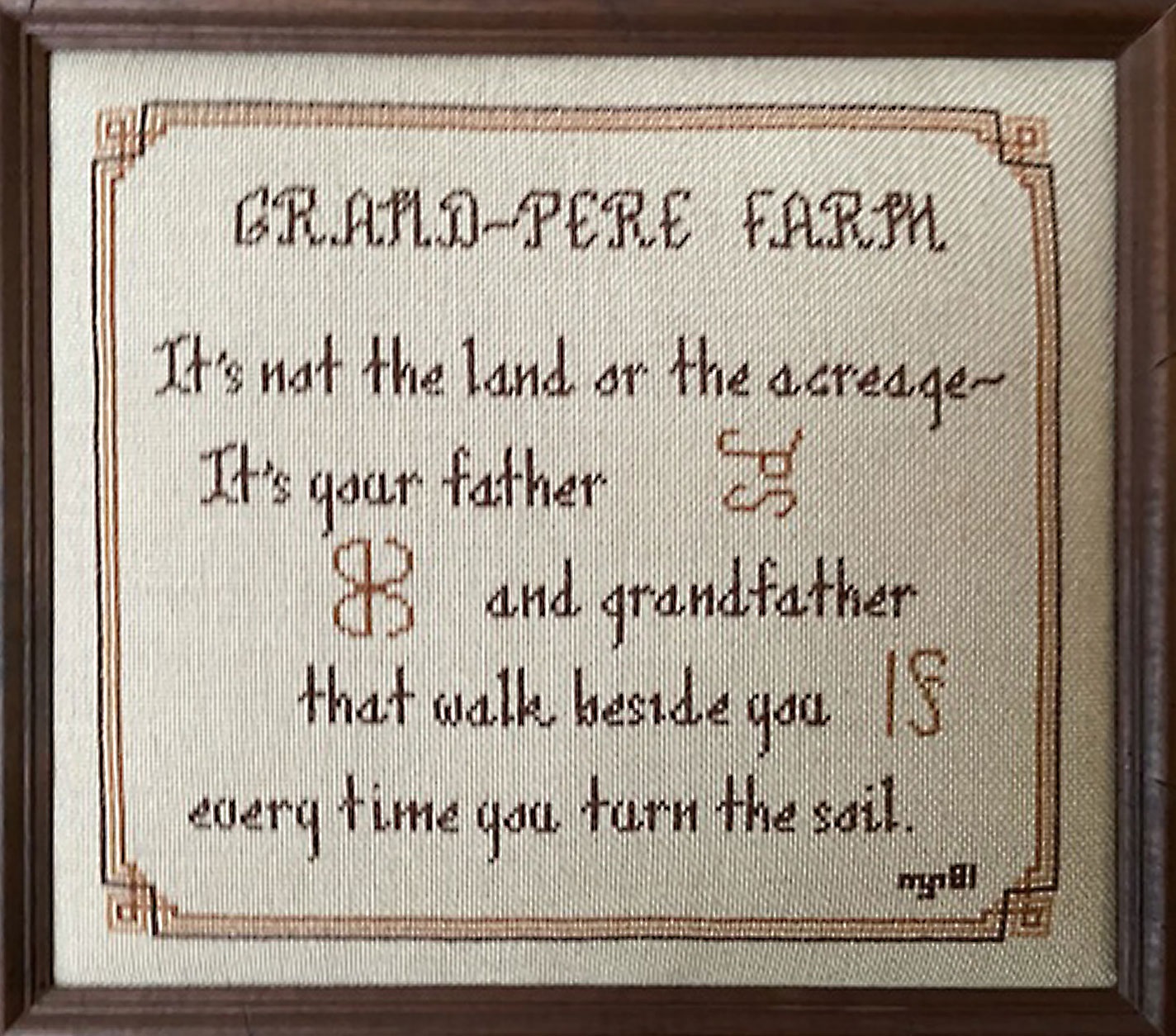

At Mona’s request, I searched through my negatives and did find a number of shots around the farm that I had completely overlooked. For me, a photograph I’d taken of four branding irons held no special meaning, and I had never thought to print it. I shot several exposures, probably because the scene was so nicely lit when I opened the barn door, and there they were, covered with cobwebs. But to Mona, this was more than a still life. To her, these branding irons symbolized the generations of Youngs who have lived on that piece of land. Forty years ago she cross-stitched a wall hanging for her father based on the family brands.

Branding irons.

As for the story about Nonc Tom buying the Ford with no back seat, Mona set me straight. “The real story of the car with no back seat,” she wrote to me, “was that PaPa gave my dad his ’36 Coupe when he went to college in 1951. It was a two-seater which PaPa really liked and wanted his new car to have that same two-seat option. Since they no longer made two-seaters, PaPa ordered a ‘business coupe’ which was built for salesmen in mind to transport their sample cases with ease, hence no back seat.”

The only upgrades were a stove, refrigerator, and a space heater in the bathroom.

Young is the source of the accurate oral history of Nonc Tom’s place. As my correspondence with Mona continued, my fifty-year-old mental image of Nonc Tom started to show cracks—thanks to the information that Mona’s father had uncovered. The story I told in my book was amusing, but it didn’t give an accurate picture of Thomas Young. He was obviously more aware of the world beyond his own farm than I had ever imagined, down to the subtleties of the latest Ford lineup.

Mona reflected on her own childhood memories: “I think the folklore regarding my great-grandfather may have been due, in part, to him being a very private man. In truth, I remember him as a very humble man who worked hard, loved his family, and was sometimes, much to his family’s chagrin, stubbornly tied to the old way of doing things.”

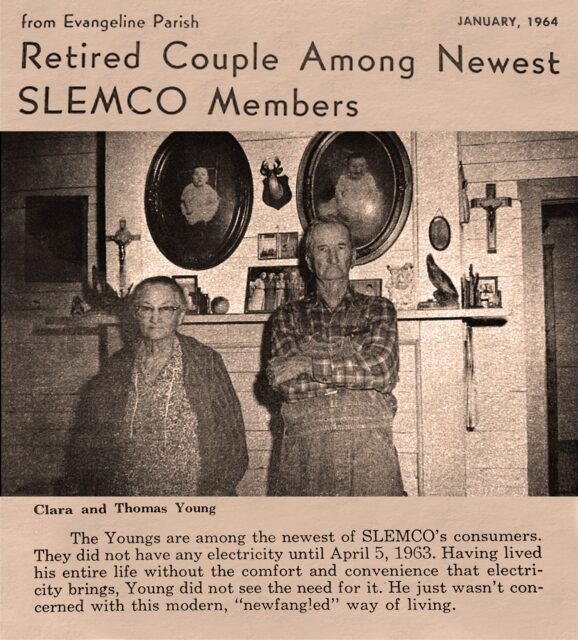

Nonc Tom is 83 in this picture, and you can bet that he didn’t use the word “newfangled” as quoted here. He spoke only French.

For me, the most amazing revelation was a JPEG that Mona sent me—a yellowed clipping from the January 1964 customer newsletter of SLEMCO, the electric cooperative. There stood Nonc Tom and his wife Clara, posing for the flash camera in front of our old fireplace. What a shock to meet them after all these years! Apparently it was Clara who had lobbied for modern appliances. According to the story in the newsletter, Nonc Tom had resisted, but he adapted and presumably enjoyed the “comfort and convenience that electricity brings” until he died in 1966.

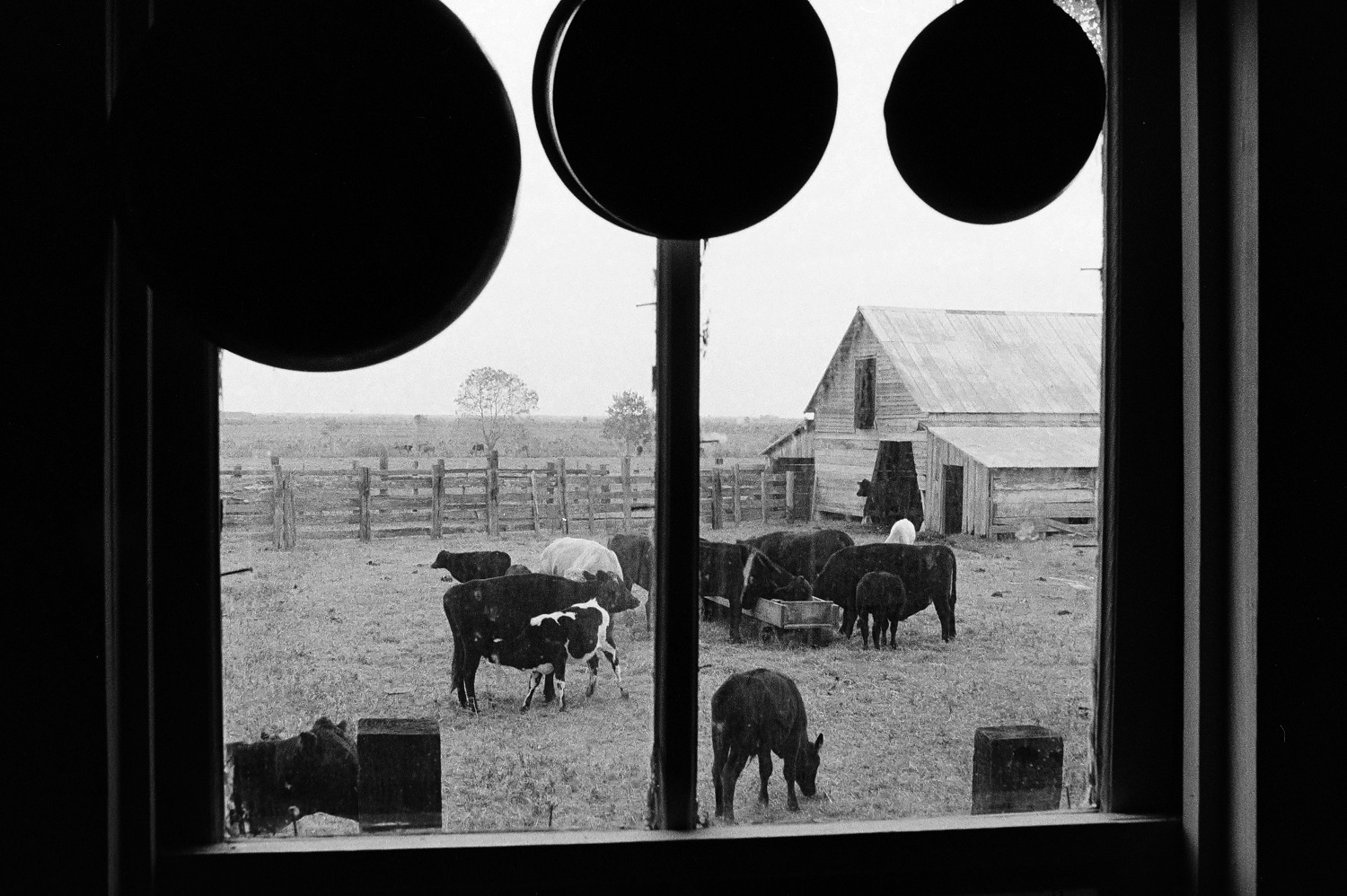

Nonc Tom’s old house burned to the ground only a year after we left. Lightning strike, the family thinks. In 1976, John and Lula started building their Spanish-style house close to the old place, creating Grand-Père Farm. Outbuildings were taken down, and the beautiful old cypress lumber was recycled into a new barn. Lula passed away in 2019. There’s a lake—Lac Clara—where the corral outside our kitchen window used to be. There’s renewed life on what the family now calls Grand-Père Farm. But it wouldn’t surprise me if there are some old-timers like me who still call it Nonc Tom’s.

Feeding time.

After leaving Basile in 1974, Ron Stanford went on to a career as a documentary filmmaker and ad agency creative director. He and his wife Fay live in the Philadelphia suburbs.