Dewey Balfa

Dewey Balfa was a Cajun musician and cultural activist who emerged in the 1970s as an effective spokesman for the grassroots Cajun identity movement.

Louisiana State Museum

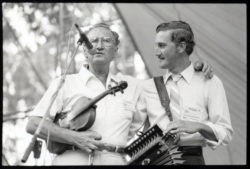

Dewey Balfa (left) performs with Robert Jardell.

Fiddler and songwriter Dewey Balfa, one of Louisiana’s best known and most influential Cajun musicians, was a dedicated spokesman for the grassroots Cajun identity movement. Beginning in the 1970s, Balfa helped convince cultural elites that Cajun music was an important means of preserving Cajun French. Often accompanied by his brothers, Balfa regularly performed at folk festivals throughout the United States, introducing Cajun music and culture to an audience outside his home state. In recognition of his efforts as a musician and cultural activist, the National Endowment for the Arts awarded Balfa the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship in 1982.

Early Life and Influences

Balfa was born March 20, 1927, in Grand Louis, a small settlement not far from the town of Mamou. His parents, Charles Balfa and Amay Ardoin Balfa, were sharecroppers, and Dewey worked with them in the fields. The Balfa family was musical, with several generations of fiddle players dating back to his great-grandfather. He also learned traditional songs from his mother. His parents encouraged their children to pursue their musical interests and, by their teenage years, the Balfa sons (Will, Burkeman, Harry, Dewey, and Rodney) were accomplished musicians who formed their own string band. With accordionist Hadley Fontenot, their neighbor, the Balfa brothers soon found themselves in demand for local dances. Balfa was highly influenced by Cajun fiddlers like Leo Soileau and Harry Choates, as well as western swing fiddlers such as Bob Wills and Cliff Bruner.

At the outbreak of World War II, Balfa moved to Orange, Texas, to work in the shipyards. He also spent several years as a merchant marine during the mid- to late 1940s. Though well known as a musician, Balfa always held other jobs, including selling insurance, running a furniture store, and driving a school bus. During the 1950s, he made his first recordings with Elise Deshotel for the Khoury label in Lake Charles. He enjoyed great popularity as a player with dance bands in southwestern Louisiana, particularly the area around Basile, where he eventually settled.

During the immediate post-World War II era, many of the Cajun musicians around Basile experimented with integrating the accordion into the string band format. The Balfa brothers formed a working relationship and friendship with legendary accordionist Nathan Abshire, who was at the heart of this new movement. While Balfa experienced great success in this new style of Cajun music, he grew concerned about the decline of traditional singing and playing.

Cultural Activism

In 1964 Balfa, accordionist Gladius Thibodeaux, Revon Reed, and Louis LeJeune were invited to perform at the Newport Folk Festival. Having only performed in dance halls, Balfa was shocked at the size of the crowd (an estimated 17,000). He was also initially confused by the fact that the audience listened—rather than danced—during his performance. The experience radicalized Balfa’s thinking about the importance of Cajun culture and music. He became active on the festival circuit and performed again at Newport in 1967, this time with his family band. His role at festivals gradually moved beyond performance to include workshops for other musicians interested in his style. In these workshops and on stage, Balfa wove the story of Cajun history into his performance narrative, exposing the world outside of Louisiana to Cajun culture and history.

He also worked closely with academics and filmmakers and was a driving force behind the “Tribute to Cajun Music” in Lafayette, an event that eventually evolved into Festivals Acadiens. The success of the tribute encouraged the Council for the Development of French in Louisiana, an organization that preserved and celebrated Cajun culture. Balfa was one of the earliest activists to understand that preserving French meant nothing if it was not integrated into people’s daily lives. And music, Balfa saw, gave people something to “do” in French. He also urged the teaching of Cajun French rather than formal, academic French in schools. Balfa frequently spoke in public schools about the history of the Cajuns and Creoles and integrated music into those lectures. Filmmakers frequently featured Balfa in documentaries, so much so that they sometimes focused on prairie Cajun culture to the exclusion of the bayou culture often identified with Cajuns.

Music Contribution and Significance

Balfa recorded actively from the 1960s until his death. Most of his studio recordings were made for the Swallow label of Ville Platte. Perhaps the most important were two volumes released as The Balfa Brothers Play Traditional Cajun Music. These records, released in 1965 and 1974, reintroduced many traditional songs into the Cajun repertoire. They also revealed Balfa’s focus and perfectionism. The brothers recorded many times with Nathan Abshire, with whom they often performed at folk festivals. Tensions within this band eventually led to its disintegration.

In 1979, Dewey’s brothers Will and Rodney were killed in a car crash. Their deaths deeply affected Balfa, but he continued to perform with friends and other musicians such as D. L. Menard, Marc Savoy, and the Ardoin family. In addition to his studio recordings, Balfa is featured on many field recordings and live performances at folk festivals. These recordings reveal how Balfa integrated his cultural message into every performance.

Balfa remained active as both a musician and cultural ambassador until his death on June 17, 1992, of liver cancer. His work lives on in the Dewey Balfa Cajun and Creole Heritage Week, held in Ville Platte, which teaches young musicians to play and to value cultural heritage. His daughter, Christine, also performs with several groups, including Balfa Toujours and Bonsoir Catin, an all-female Cajun band.