Latest

Messages and Messengers in Public Health Crises

A conversation with epidemiologist Julie Hernandez

Published: April 17, 2020

Last Updated: August 25, 2021

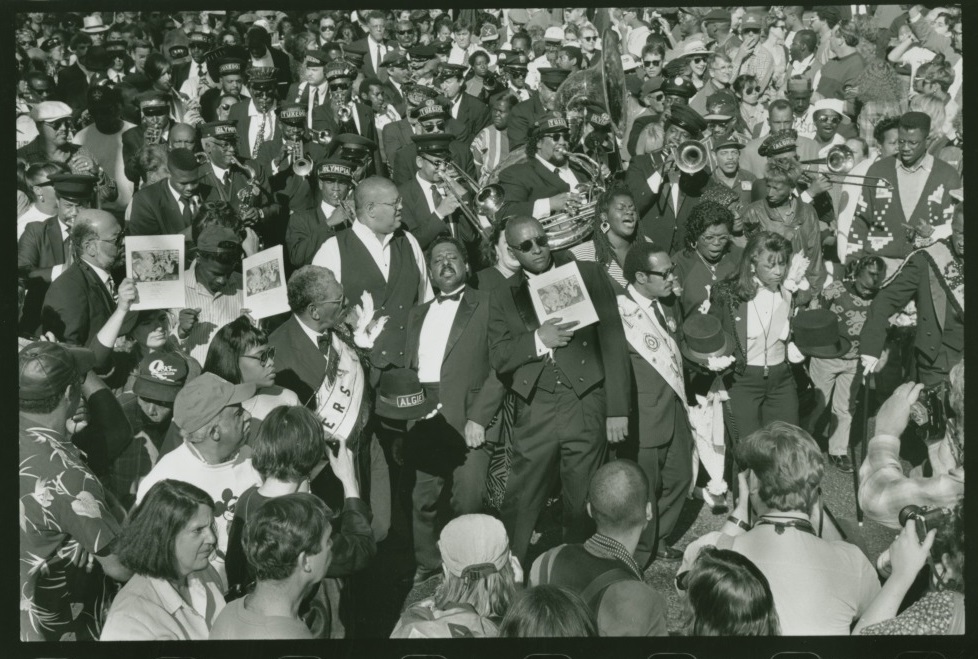

Photo by Michael P. Smith. © The Historic New Orleans Collection

Funeral of jazz musician and Fairview Baptist Church Brass Band–founder Danny Barker. New Orleans, March 17, 1994.

Chris Turner-Neal: Given your experience looking at other outbreaks in other parts of the world, what similarities have you seen in different cultures’ reactions to outbreaks?

Julie Hernandez: The common denominator is that people tend to be reactive rather than proactive. In an outbreak, the public health goal is to get in front of it, to predict where we think it’s going to go next and to prevent that from happening. In many respects, public health people have a weird job, because what’s important for us is that nothing happens. My goal is to make my days and the days of everybody that I care for through my work as boring as possible. And that’s kind of a difficult mentality to convey in any culture.

Everybody knows the doctor. The doctor you seek, you go see the doctor, and you feel better, and you say, “Oh, the doctor cured me.” If you have a public health approach, the objective, of course, is that nobody gets sick in the first place. It’s literally a good day when nothing happens. And so, for an infectious outbreak, I think it’s even more strange, because now, we are asking people to make dramatic changes to their lives so that literally nothing happens.

We saw a lot during the last Ebola outbreak in West Africa that one of the main modes of transmission was funerals, because there’s that tradition of washing and touching the body. And that’s when the body’s at its most virulent, and you’re the most likely to catch the disease. We had to ask something that is extremely difficult from people, which is to change the way they bury their dead. To some extent it’s a stretch to compare it, but when Ellis Marsalis died, there was no second line in New Orleans. What could be more symbolic than that? So, we’re asking people to change their way of life in very brutal ways. With an infectious outbreak, you’re going to ask people to change the way they eat, the way they work, the way they bury their dead, the way they interact with their family, the way they have sex, in the case of HIV. So, you are asking people to change behaviors that are fairly deeply anchored and that are a big part of their identity. And of course, you’re going to find resistance to that, because if I’m telling you, you have to change the way you have sex or the way you bury your dead, you’re going to try to negotiate with that.

And so a connected similarity is that people tend to think of themselves as the hero, not the victim. They think they can negotiate. They think somehow they’ll squeak by, so you have a lot of resistance to these demands that we change what we do. We like to do things. We like to fight back. And here, the best way to fight this virus in particular is by being as passive as possible. If everybody could sit down in front of their TV for the next two weeks and not move, I’d be the happiest public health person in the world. But people want to do things. And by doing things, they endanger themselves. In a context like sub-Saharan Africa, they have no other choice but to do things. We’re seeing COVID appearing in Kinshasa right now, and in the rest of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Social isolation in Kinshasa is simply not feasible. People don’t have a fridge; people don’t have electricity. People who live with less than $2 per day have to go out every day to sell a little something to make a little cash, to buy a little something to feed their family. The idea that you could stash food for a week in your house, it’s simply not going to happen.

Stay home, wash your hands. Basically that’s the message; it’s not that complicated. But, to some extent, your messenger is more important than your message.

CTN: Tell me about some ways you’ve seen local cultures and local traditions shape public health responses. Are there different ways you have to communicate to people in situations like this, dependent on their cultural background?

JH: Yes. And it’s not necessarily a matter of cultural background, but it’s true of pretty much every crisis. The person conveying the message has to be someone who is trusted. So, it’s not so much what you say to people, but it’s who says it to people. We saw this in a very different context in New Orleans during Katrina: part of the reason why the evacuation was not heeded was because people didn’t trust the source. In other countries, or in other places, you may have to rely on religious leaders, because they are the only ones who, when they say something, people listen. There have been a few articles that have come out of Brazil where gang leaders are the only ones that that can convey the stay at home order in slums, for example.

So you have very nontraditional emergency actors, but they are the ones who have previously built trust with the population, for whatever reason. When those guys say something, they are believed by the population, and the population is going to do what they say. And I think that’s key. With Ebola in Liberia and Sierra Leone, the funeral traditions only really changed when a religious leader came in and said, “Listen, in this time of crisis, it is okay to bury your dead in a different way.” But religious leaders were, to some extent, the only ones with the power to say that. You saw something very different in Nigeria. Nigeria had a really good response to the Ebola outbreak. And one of the resources they mobilized was Nollywood, the local film industry. So, Nigerian movie stars, singers, et cetera, and the Ministry of Health recruited those guys to convey the message on their social media platforms, and Nigerian youth is as addicted to social media as everywhere else. So, Nigerian singers and actors were recruited to convey those messages. And nowadays if you look at what’s happening in India, Bollywood actors are big spokespeople for the confinement order, and they are posting videos and they’re telling people, “I’m staying home. You should stay home.” In a country where half of the population thinks the authorities are corrupt, you have to rely on those nontraditional conveyors for the message. And maybe that’s the best lesson to learn.

If I can give another example, I grew up in one of the poorest suburban districts outside of Paris, which nowadays is one of the hardest hit by the virus. A number of neighborhoods are predominantly Muslim. And one of the things I’ve been wondering is: why are we not using the imams? Because they are the respected figures that can convey a message to youth in those neighborhoods to stay home for the benefit or the wellbeing of their parents and their grandparents. These guys are never ever going to listen to whatever comes from a government that has been nothing but unsupportive and sometimes violent towards them in recent years.

Stay home, wash your hands. Basically that’s the message; it’s not that complicated. But, to some extent, your messenger is more important than your message.

CTN: In these other outbreaks, have you run into issues with misinformation or fake news? Does it spread on social media as it does here?

JH: Oh, absolutely. And it’s tied to that mistrust in the authorities. People don’t fundamentally change their own beliefs in times of crisis. Whatever you believe now is going to be exacerbated by the crisis. People believe this is a hoax. They think this is a disease that was invented in a lab, possibly by the Chinese, possibly by the Americans, possibly by Bill Gates. “Who knows?” “Because we’re trying to control the world population.” “This is a disease that affects only white people.” “This is a disease that affects only black people.” “This is a disease that was invented by the Google corporate deep state to control the economy.” All of these things that I’ve quoted could have come from a WhatsApp group in the Congo or a Reddit page coming out of Mississippi.

Medical researchers or scientists are used to taking their news from scientists and researchers and academics, and we tend to say, “Listen to the people who are informed. Listen to the scientists. Listen to Tony Fauci.” But just as people aren’t going to change their beliefs or their behaviors, they are not going to change their source of news because there is a crisis. If I get my news from Twitter, then that’s where the news is going to have to reach me. That’s where the message is going to have to reach me.

You have the same rumors around Ebola. “This is a curse.” “This was invented by white people because they’re trying to decrease the African population.” “If you go to the hospital, you will die.” And the way that Nigeria effectively addressed those rumors was by meeting people on their own territory. They put their message on Twitter, on WhatsApp, on Facebook. Because somebody who’s getting news from social medias that is fake or distorted is not going to say, “Oh, let me see what the Ministry of Health is saying about this as well, to compare.” They are going to be looking in the same place. That’s where you have to put the message.

CTN: Is there a further point about infection control or epidemic response that you’d like to share?

JH: I told you about the quotes that could have been taken from anywhere. I don’t know if it’s because by now the entire world has watched the same TV shows and the same movies, but it’s curious, sometimes funny, and a little bit endearing that people come up with the same conspiracy theory no matter where they are in the world. As human beings, we tell ourselves similar stories about these things.

The crazy shit I’ve heard about Ebola in West Africa is pretty close to the crazy shit I’ve heard about COVID in New Orleans. Maybe we could recognize that we’re all overwhelmed and scared, we’re all doing somewhat silly things to give ourselves the illusion of control. We’re all going through this as ourselves. There’s that idea, which also comes largely from movies and our collective psyche, that crises transform people. What I’ve seen, from Katrina and from outbreaks in other places, is that crises don’t transform people. People go through crises as themselves. People who are going to be very sensitive to race issues are going to be even more sensitive to race issues. People who are strong and silent types are going to be even stronger and more silent. We go through these situations as ourselves, and we all tell ourselves the same stories for comfort and for hope. And there is a great common denominator there.