More Precious Than Rhinestones

Louisiana’s festival queens act as local advocates and bearers of tradition

Published: November 30, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Kathryn Shea Duncan

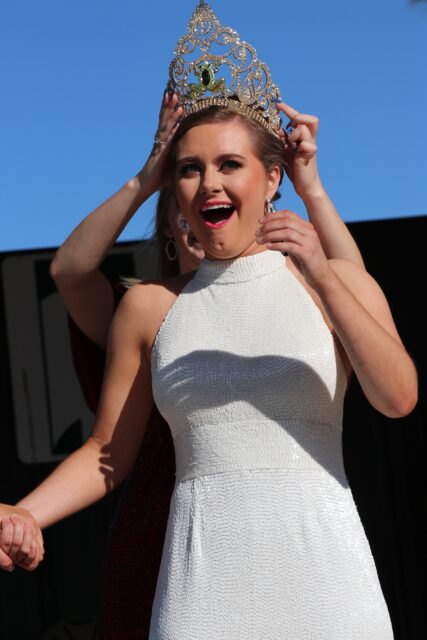

Kathryn Shea Duncan, as International Rice Festival Queen, meets an admirer at the Louisiana Fur and Wildlife Festival.

Louisiana has more queens than you can shake a tiara at. They reign over rice, peaches, fur, strawberries, citrus, crawfish, gumbo, jambalaya, frogs, black pepper, and in Morgan City, the uneasy-bedfellows title of shrimp and petroleum, the oldest agricultural festival crown in the state. Usually a young woman in her late teens or early twenties, the queen serves as a sparkling ambassadress for the town, its festival, and in many but not all cases, the festival’s namesake commodity. These festivals celebrate the small town in an urbanizing world and pull needed tourist dollars into rural areas. They also offer a locus for community pride and a local identity to rally around. Abigail Fruge, the current Rayne Frog Festival Queen, points out that the city is covered in frog decor even during ordinary times; outside the clinic where she works is a frog statue outfitted in medical garb. A formal representative like a festival queen is a natural extension of the community identity and spirit: everyone is excited, the whole town pulls together to pull off a successful festival, but all Rayne can’t get in a bus and tool around the state talking frog legs. A queen can.

Most queens are chosen in pageants, and while beauty helps (as it does everywhere), more is needed to become true Louisiana royalty. Many young women come up through the pageant system, competing for lower-profile titles: Kathryn Duncan, 2017’s Crowley Rice Festival Queen, came to the rice festival pageant having been a Miss Crowley and a Miss Acadia Parish. Fruge, who in addition to her role as the current Rayne Frog Festival Queen is also a former Miss Natchitoches Meat Pie, Ville Platte Queen Cotton, and Miss Mardi Gras Southwest Louisiana, approaches the pageants like job interviews. This approach was echoed by Duncan, who has never interviewed for a job she didn’t get and credits the organization, poise, and people skills she developed as a pageant participant for this run of success. Duncan and Fruge described significant research processes into their festivals and products, noting that this both prepared them for the roles if they were chosen and allowed them to demonstrate dedication to the judging panel. (Duncan admitted going a bit overboard—she had been so excited that she hadn’t eaten or drunk enough the week of the Crowley pageant, and needed an IV the evening between the private judges’ interview and the public pageant.) Yes, there are usually costume and evening gown competitions, and the successful competitor must present a put-together appearance at events around the state, but a good queen is less “a pretty face” and more “able to put on her face in the car between festivals while remembering the names of everyone she’s met.”

Jennifer Autin, the 2002 Frog Festival Queen and current head of the Rayne Chamber of Commerce, agrees. She identifies the period around her reign as a moment when the emphases of the pageants changed: you no longer had to “look a certain way,” and the service to the community became more central. Autin said some of the most important work of her reign occurred “without her crown, in the trenches,” volunteering with children and helping post-hurricane cleanups. While she acknowledged “crown chasers,” contestants more interested in a fully stocked mantelpiece of trophies than a connection to communities and traditions, in her experience successful queens are far more likely to be givers than takers. Many work in local organizations that boost the town or region, like Autin herself and Duncan, who works at the Lake Charles convention and visitor’s bureau.

Treating the pageant preparation process like a job interview is a successful strategy because being queen is much more work than outsiders realize: under non-COVID circumstances, a Louisiana festival queen can expect to travel most weekends of her year-long reign. The specifics vary, but they can expect to go to many, many other festivals, along with trade shows, conventions, and demonstrations, representing the town, region, particular festival, and industry. 2021 Plaquemines Parish Seafood Queen Kristin Nash noted that, even during the state’s uneven emergence from the pandemic, she’s traveled to represent the festival and industry at other celebrations and toured swamps, cotton fields, and factories. As COVID has forced cancellations and delayed festivals, many young women have been asked to stay on as queen during the crisis, until normal operations and scheduling can be restored. These extensions of reigns—it’s tempting to call them regencies—ensure that the various organizations have someone they can send to the events that do take place who can effectively represent the group. The importance of keeping a queen in office during the uncertainty is perhaps best exemplified by the Louisiana Association of Fairs and Festivals’ own queen, Danielle Brianne Jones, whose reign has been extended like those of many of her sister queens. Fruge, whose current reign has included serious hurricanes and much of the coronavirus pandemic, also noted that festival queens have a platform from which to model good behavior and encourage relief efforts, remarking that the crisis-dotted years of 2020 and 2021 have helped her understand how to use her role effectively.

One of the country’s and the state’s greatest assets is the involved citizen: the devoted local historian, the fundraiser dedicated to the small museum, the go-getter who instead of “what a shame” says “let’s fix it.”

Most of the women I spoke with for the article, though happy to talk about an experience from which they benefited and that they remember fondly, also felt they had to explain it: several explained that it wasn’t like Toddlers and Tiaras and that there’s much more camaraderie than conflict among contestants and fellow queens. Traditionally, rice festival queen finalists hang out and go trail riding the night before the pageant; they’re among the most stressed people at the festival, and the sisterly canter allows for some decompression. Kenley Lemoine, Miss Louisiana Crawfish Festival 2021, has worked to include the festival’s junior queens in as many events as she can, since the smaller events calendar this year and last has meant fewer opportunities for them to participate in festival business. A particularly strong sorority exists among cohorts of queens, that is to say, the women from different festivals whose reigns overlap and who see each other more or less every weekend as they travel, building friendships and following each other’s successes.

The queens convene at two events in particular: the Queen of Queens Pageant and Washington, DC, Mardi Gras. The Queen of Queens Pageant, carried out under the auspices of the Louisiana Association of Fairs and Festivals, sees a competition Lemoine described as “the Miss Louisiana of festival queens.” Lemoine will be one of about seventy queens (the number varies by year, as individual queens opt in or out) who will present themselves as the pinnacle of the Louisiana festival queen tradition and compete for the overall crown. Queens compete in private interviews, formal wear, and costumes—the grand themed regalia we’ve all seen, with rice crowns, crustacean sashes, and sugarcane trains—with the top fifteen answering live questions onstage.

DC Mardi Gras is put on every year by the Mystick Krewe of Louisianians, exiles whose fates have pulled them to the capital. Many of these people are government officials, of course, and the chairman of next February’s hoped-for event will be Garret Graves, the US Representative for Louisiana’s Sixth Congressional District. The great, the good, the fun-loving, and the connected of Louisiana’s federal presence can be spotted there, reinforced by a complement of Louisiana’s festival queens. Queens of the oldest, most venerable festivals who sent the first delegations to DC—rice, crawfish, sugar, and shrimp and petroleum—are joined by a smattering of ladies from newer festivals for a whirlwind VIP experience that Duncan is still amazed to recall several years later: “We went to a tea party at a place where we had to leave our phones outside because First Ladies sometimes ate there, and another night we went to a party with Flo Rida.” After these “lesser” parties comes the ball, at which the queens appear, contributing to the national profile of the state and underscoring its culture and industries.

The cultural and agricultural landscape that underpins the small-town festivals shifts; change is inevitable, and especially so over the past few generations of urbanization, economic upheaval, and climate change. Opelousas’s long-running Yambilee Festival, celebrating sweet potatoes, was discontinued in 2012; Fruge spoke wistfully of this festival as one that is fondly remembered and that she can imagine reemerging, despite the harsh judgment captured on the event’s Wikipedia page: “discontinued due to . . . extreme lack of public support.” (An optimist, of course, might note that someone did care enough to create the Yambilee Wikipedia entry.) Ville Platte’s Queen Cotton rules over a land that now produces more valuable corn and soy. Autin noted that smaller contestant pools appear at many festivals now—the festivals are still popular, but fewer girls reach for the crowns.

A New York Times photoessay published in February 2020 focused on queens who specifically represent agricultural products and cast the tradition as one of many threatened by the environmental challenges of climate change and land loss that menace so much of the state. Journalist Jeanie Riess cites storm-driven saltwater intrusion into rice fields and freshwater damage to oyster beds as concrete examples of realms besieged; most Louisianans could add examples from their own experiences. Fort Jackson in Plaquemines Parish hosted the local Citrus Festival and its expansive court from 1970 until the site was badly damaged by Hurricane Katrina and subsequent storms; for years, the festival was held outside the traditional venue until repairs made a return possible shortly before the pandemic. My own research for this story was forcibly redirected by Hurricane Ida’s damage to the hometowns of royalty I’d hoped to consult, and I conducted my final interview from an Airbnb in Birmingham waiting for power to be restored to my home in New Orleans—with Kristin Nash, herself evacuated from her Port Sulphur home.

One queenship in particular directly addresses the state’s environmental challenges. Houma’s Rougarou Fest, a late-October celebration of the region’s indigenous boogeyman-cum-mascot, adds coastal-issue education to its slate of spooky fun, with the festival supporting the educational nonprofit South Louisiana Wetlands Discovery Center (SLWDC). The Rougarou Queen is chosen not in a pageant but from among the festival volunteers to ensure the selection of the best advocate for the festival and the issues it addresses. The incumbent, Shannon Eaton, wasn’t expecting to be chosen, but threw herself into preparation. Rougarou queens design their own gowns, so Eaton spent a spring break learning to sew a flamenco dress pattern that would best suit her tribute to the Louisiana wild iris, Iris gigantis. Her choice came with a message: the wild iris is threatened in many parts of the state by herbicide runoff and can most easily be found in hard-to-access areas, depriving many Louisianans of its beauty. Eaton volunteers with the Iris Conservancy, which rescues wild irises growing in areas where they may be killed and replants them in protected spaces. Since she’d been chosen and hadn’t competed for crowns like many other queens, Eaton studied the women who did the traditional circuit, looking to them as examples of how to use her new platform—she adds that the environmental focus of the Rougarou Fest and the SLWDC gave her a sense of urgency, spurring her to do the most she could with the role. While there is no volunteerism requirement, Eaton hopes that her successor will take it up along with the scepter. One might even whimsically hope that, as more people embrace the adaptations needed to secure Louisiana against an uncertain future, we may see Miss Coastal Restoration and Miss Renewable Energy gracing public events in the years to come.

One of the country’s and the state’s greatest assets is the involved citizen: the devoted local historian, the fundraiser dedicated to the small museum, the go-getter who instead of “what a shame” says “let’s fix it.” Louisiana’s festival queens are what these people look like on the cusp of adulthood. These young women take a significant amount of time out of their high school or college years to research rice, read up on strawberry farming, learn how to sex a crawfish, and explore how they can become advocates for the small towns and local traditions that much of the modern world might abandon. Fruge, who has held several titles, singled out Rayne and its frog festival for particular praise: “It’s the quintessential banding together. That’s why it has lasted, and that’s why it will last.” As these festivals continue and as the small towns persevere, many of the people shepherding them along will be former festival queens, looking to the future from under sugarcane tiaras.

Chris Turner-Neal, the managing editor of 64 Parishes, has a crown of apricots that he is not entitled to wear.