Summer 2018

Mrs. Officer

New Orleans’ first policewoman endured controversy to patrol vice districts

Published: May 31, 2018

Last Updated: March 18, 2019

Courtesy of Louisiana Research Collection, Tulane University.

In June 1915 Monahan began patrolling the notorious Milneburg resort town on the shores of Lake Ponchartrain.

By the summer of 1915, Milneburg was still the place to escape stifling summer temperatures, to drink and dance on Sunday (violating the Sunday law), for women to drink without being served meals (violating the Gay–Shattuck law), and for men to consort with prostitutes outside of the restricted district of Storyville (violating Ordinance No. 13,032). The summer season of 1914 saw a total of 121 arrests in Milneburg, but by July 1915 the number for the summer was already at 127. The New Orleans City Federation of Women’s Clubs (NOCFWC) had had enough of the escalating “demoralizing practices” and petitioned Mayor Martin Behrman for an official chaperone or policewoman to be assigned to Milneburg to make the resort safer for families, young women, and girls. The NOCFWC believed that a woman of “judgment and tact” could assist the police. Five years earlier, the country’s first policewoman, Alice Stebbins Wells, had been hired in Los Angeles to “protect young girls, particularly first offenders, and to keep them away from hardened criminals.” Behrman relented to the women’s demands.

Mrs. Alice Monahan was chosen out of ten applicants (although only three met the hiring committee’s “vision” of merit). Her qualifications included being an Episcopalian (she sang in the choir), running a boarding house, and being the first corresponding secretary, in 1913, for the Woman Suffrage Party of Louisiana. She was a recent divorcée who had been married three times, the first when she was fourteen, and was described as having a “fine physique” despite her “mature” age of forty-five years, thanks in part to the recent bicycle craze. Upon accepting the job, Monahan stated, “I must expect petty annoyances, and the sort of conduct with which school-boys test the patience and resourcefulness of a new teacher.” Her expectations were correct.

She was subject to threatening phone calls, false rumors, and once made the grave “mistake” of attending a boxing match.

By August, the Item announced that Milneburg’s “Sin and Satin Sunday Sessions” were a thing of the past. Monahan was so effective at de-escalating the rowdy atmosphere that the resort had gone one week without a single arrest. But not everyone was pleased. Some citizens charged that Monahan was unfit to hold the job and wanted her removed, contending that she cast “unwarranted suspicion upon the camps” by her patrolling and investigating, and that she was “overzealous” in her duties. They wanted her transferred to another district and Milneburg put back under the supervision of policemen. Mayor Behrman refused to receive the complaints unless someone could offer absolute proof of Monahan’s “unfitness.”

She did not, however, receive the same chivalrous treatment from John Quarella, the unofficial “Mayor of Milneburg.” Quarella was the biggest operator in Milneburg, owning a barroom, restaurant, dance hall, cabaret, bathing house, and ten separate camps. After an inspection, Monahan recommended to the police chief that Quarella’s three female employees living in the “feminine wing” of the bathhouse have their beds removed and sleep elsewhere. (It was speculated in the newspapers that the women were prostitutes.) Quarella refused, and had his all-night barroom permit and music permit revoked. He soon changed his mind and made Monahan’s recommendations, but not without putting her on blast to the press.

Monahan’s job was meant to end at the close of the season, but in September 1915, thirteen-year old Elizabeth Mayeur left a note for her parents stating that she was going to Conti and Galvez Streets and ran away. Mayeur was found the next evening in a dancehall, where she had been drinking beer with men and urged by scarlet women to consider new ways of earning some extra cash. NOCFWC members were outraged; they petitioned for Monahan to be employed year-round and assigned to the cabarets around the red-light district of Storyville to exercise her moralizing influence. The Item sarcastically wrote that, now that Monahan was on permanent duty, “Miss New Orleans can trip the festive tango up to the wee sma’ hours in carefully-guarded safety. For the era of the city chaperone has dawned.”

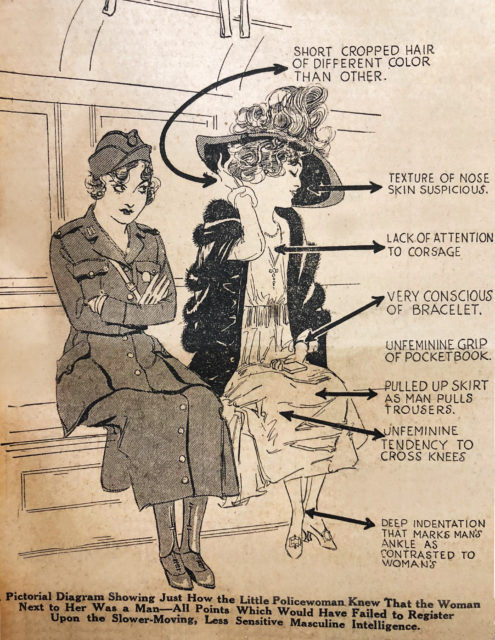

Fear of German infiltration ran high in New Orleans during WWI. This illustration from The Item diagrams the ways female police officers might detect male German spies disguised as women. Courtesy of Louisiana Research Collection, Tulane University.

Monahan happily accepted her position. However, though the novelty of her role eventually wore off, she continued to experience harassment and controversy. She was subject to threatening phone calls and false rumors (including one that she was living under an assumed name). Once, she made the grave “mistake” of attending a boxing match. Police Superintendent James Reynolds immediately reprimanded her and released a statement that no women in New Orleans would be allowed at boxing matches.

Monahan did, nonetheless, get some deserved acclaim. In May 1916, she was invited to Indianapolis to speak at a week-long conference for policewomen. Twelve states had delegates at the convention, there being only twelve states that allowed policewomen. In August, Monahan went to Charity Hospital for a gallstone operation and died a few days later. She was forty-six years old. Her death made news around the country, and although the reign of New Orleans’ first female police officer was brief, her funeral was immense. NOCFWC women took turns staying at the funeral parlor to watch over her body. Her casket was covered with flowers, including a large wreath in golden glow flowers and ferns, yellow being the color of suffragists. Men, women, and children from Milneburg came to pay their respects. One young man knelt in prayer in front of Monahan’s body, while another laid his hand on her cold forehead and said, “She saved many a young girl from wrong.” Monahan was buried with honors in Greenwood Cemetery.Multiple women applied to be New Orleans’ next policewoman, including “the largest clubwoman” in the city, six-foot-tall Mrs. Nettie Erwin, a prominent suffragist, and Mrs. Nell Malezewski, the city’s first female jitney driver. But Behrman was in no hurry to name Monahan’s successor. By statute, women could not be appointed to the police force—Superintendent Reynolds had carried Monahan on his roll as a matron—and there was no obligation to hire women as police officers, nor additional funds with which to pay them.

Still, New Orleans club women pushed on. The 1917 closing of Storyville intensified the desire for women in the police force. NOCFWC members believed that policewomen could get information from the prostitutes in their own “feminine way,” keep the prostitutes away from railway stations and military camps, find underage runaway girls, and effectively keep “Magdalenes” from returning to the former red-light district. Eventually, the mayor relented and female officers were hired, almost all of them tasked to assist women and children, as was the norm across the country.

By 1922, the International Association of Chiefs of Police set standards for policewomen, such as four years of high school, plus two years’ experience in social or educational work or nurses’ training. The preceding years had seen great movement for women’s place in society, including finally gaining the right to vote. Alice Monahan and other women like her were critical in their own way to this national movement. Even though her achievement came about through a uniquely local circumstance, it reflected and contributed to the great march for women’s progress in America.

————————

Sally Asher is the author of Hope & New Orleans: A History of Crescent City Street Names (2014) and Stories from St. Louis Cemeteries of New Orleans (2015). She contributed essays to the tricentennial books New Orleans: The First 300 Years (2017) and New Orleans and the World: 1718–2018 Tricentennial Anthology (2017). She holds two master’s degrees from Tulane University in English and Liberal Arts with a concentration in history. Her next book about Prohibition in New Orleans will be published by Louisiana State University Press.