Sound Advice

Music with Porous Boundaries

The proud eclecticism of John Fohl and Corey Ledet

Published: March 1, 2019

Last Updated: May 31, 2019

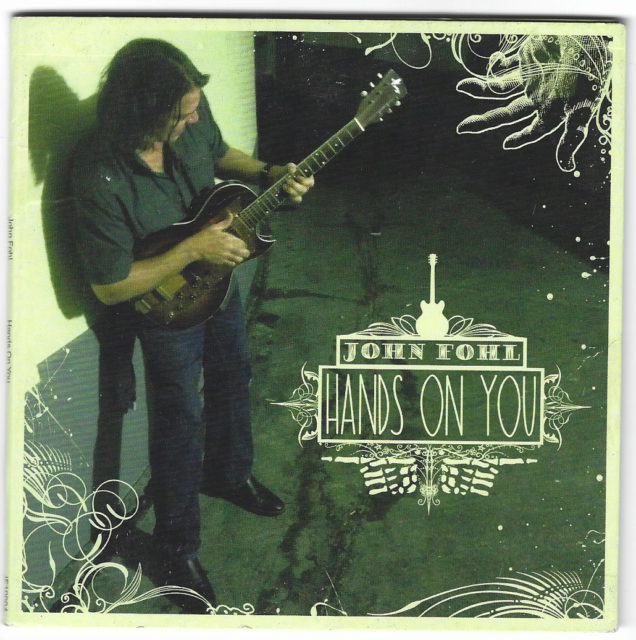

This column often emphasizes the imprecision of separating music into rigid categories that do not overlap. Such terminology tends to mean little to working musicians—especially freelancers who must adaptably play whatever is required by whoever hires them, no matter how arbitrarily it may be classified. This requisite versatile mastery, which enables self-employed musicians to make a living, also broadens their scope when creating original material. The New Orleans guitarist, songwriter, and vocalist John Fohl demonstrates such seamless command on his latest album Hands on You (JF). Fohl is a native of eastern Montana, where country music and Top 40 pop-rock dominated the local radio that he heard while growing up. Besides absorbing these influences, Fohl’s family guided him towards such bedrock sounds as the blues, and specifically to the work of the iconic blues guitarist Muddy Waters. By the mid-1980s Fohl was touring in the band of Muddy Waters’ colleague, the seminal blues/rock/R&B guitarist Bo Diddley, whose music was rich in African rhythmic retentions.

In 1996 Fohl moved to New Orleans, where he has garnered great respect as a first-rate, sought-out player in a city with no shortage of mature, estimable talent. Fohl spent a dozen years playing around the world with Dr. John, whose far-flung repertoire encompasses Latin-American rhythms, just for one example, alongside the more familiar hometown patterns of second-line syncopation. Fohl’s tenure with this venerable New Orleans R&B pianist included recording on the Grammy Award-winning album City That Care Forgot (429 Records), a post-Katrina screed for which Dr. John pointedly (and temporarily) renamed his band The Lower 911. Fohl has also worked with the diverse likes of the blues and swamp-pop diva Carol Fran, the eloquent pop-rock songwriter and vocalist Susan Cowsill, and the chanteuse Ingrid Lucia, among many others. At this writing Fohl performs frequently—at home and overseas—with a spectrum of musicians including the roots-rocker Anders Osborne and the blues harmonicist Jumpin’ Johnny Sansone, in co-billed formats or as an accompanying band member. Fohl also appears regularly as a solo artist.

In 1996 Fohl moved to New Orleans, where he has garnered great respect as a first-rate, sought-out player in a city with no shortage of mature, estimable talent. Fohl spent a dozen years playing around the world with Dr. John, whose far-flung repertoire encompasses Latin-American rhythms, just for one example, alongside the more familiar hometown patterns of second-line syncopation. Fohl’s tenure with this venerable New Orleans R&B pianist included recording on the Grammy Award-winning album City That Care Forgot (429 Records), a post-Katrina screed for which Dr. John pointedly (and temporarily) renamed his band The Lower 911. Fohl has also worked with the diverse likes of the blues and swamp-pop diva Carol Fran, the eloquent pop-rock songwriter and vocalist Susan Cowsill, and the chanteuse Ingrid Lucia, among many others. At this writing Fohl performs frequently—at home and overseas—with a spectrum of musicians including the roots-rocker Anders Osborne and the blues harmonicist Jumpin’ Johnny Sansone, in co-billed formats or as an accompanying band member. Fohl also appears regularly as a solo artist.

Hands on You distills elements of all the music mentioned above, along with tinges of ’60s and ’70s rock à la Van Morrison, Little Feat, and Cream. More specifically there is a strong similarity, in terms of their keen timbre, between Fohl’s voice and that of Morrison during his heyday. This resemblance is especially evident on the opening song, “This Side of the Grass,” a reflection on mortality that Fohl sums up with the comment “how silly it is to live forever.”

…I’m gonna find myself some shaman

Wholl help me outlive everyone

So get the old gang back together

I’m gonna tell ’em I like it better

On this side of the grass.

Ain’t gonna see me wearin’ no halo

Ain’t gonna come back wearing wings

If you see them coming with their golden feathers

Just tell them I like it better

On this side of the grass

I’m gonna hold on to my vision

I’m gonna hold on to my sense

I’m gonna see one hundred and fifty

Ain’t gonna leave my lovely city

So get the old gang back together

So I can tell ‘em I like it better

On this side of the grass.

Fohl delivers his soulful, convincing vocals in a straightforward manner devoid of ornamentation and effectively punctuated by silent spaces. His guitar playing is more complex and at times intense, although never frenetic. On the mid-tempo “This Side of the Grass” Fohl connects his vocal lines with continuous sustained single-note phrases, in a manner resembling a call-and-response dialogue. The up-tempo “Go Again” climaxes in a solo of increasingly urgent bent-note licks, played with dead-on rhythmic certainty, before dramatically resolving its harmonic tension with a single resonant chord. Conversely, chords that seem to float like clouds create a dreamscape for Fohl’s solo on “Army of One,” a blunt, evocative tale of life as a musician.

Fohl is accompanied throughout the album by a small band of local A-list veterans on bass, drums, and various keyboards, with the occasional use as well of accordion, harmonica, and background vocals. In the best New Orleans tradition, these players share a feel that is simultaneously tight yet fluid. Each part makes a statement and then bows out so that the songs never become cluttered. In terms of its mixes and recording quality—and the all-around fine performances—this artist-funded album has a thoroughly professional big-budget sound, and Fohl’s self-production recalls the less-is-more sensibility of Allen Toussaint. Appropriately, Hands on You includes a heartfelt tribute to this New Orleans renaissance man, featuring evocative piano work by John Gros.

Other highlights from Hands on You include the spiritual reflection of “Shinin’,” an exploration of relationship complexities on “Taste Your Tears,” the introspective “A World Undone,” and the lustful zydeco groove of “I Can’t Wait.” Such variety, presented with well-paced cohesion and consistent quality, raises the question of correct categorization. Hands on You combines instrumental elements of blues, rock, funk, R&B, Crescent City syncopation, and zydeco from Louisiana’s western parishes. In addition, the emotional depth of some of Fohl’s lyrics invite comparison to singer-songwriter genre, in the best sense of that term. What, then, is the most accurate descriptor for this hybrid album? The open-ended label of “contemporary New Orleans music” will suffice.

Zydeco is also a hybrid, albeit one with obvious primary sources. These include the early Creole and Cajun music of southwest Louisiana and that music’s respective Afro-Caribbean/ French origins, plus zydeco’s signature instruments—the accordion and the frottoir (also known as the rub-board). But zydeco also blends in blues and R&B, swamp-pop, country, reggae, and, more recently, rap and hip-hop. Rap music’s influence has created somewhat of a divide on the current zydeco scene between a varied repertoire—in terms of song forms that include waltzes, for example—and a bass-heavy sound, at times repetitious and predominantly sung in English. Some zydeco bands straddle this malleable cultural gap by playing both styles, depending on the preference of the audience at hand.

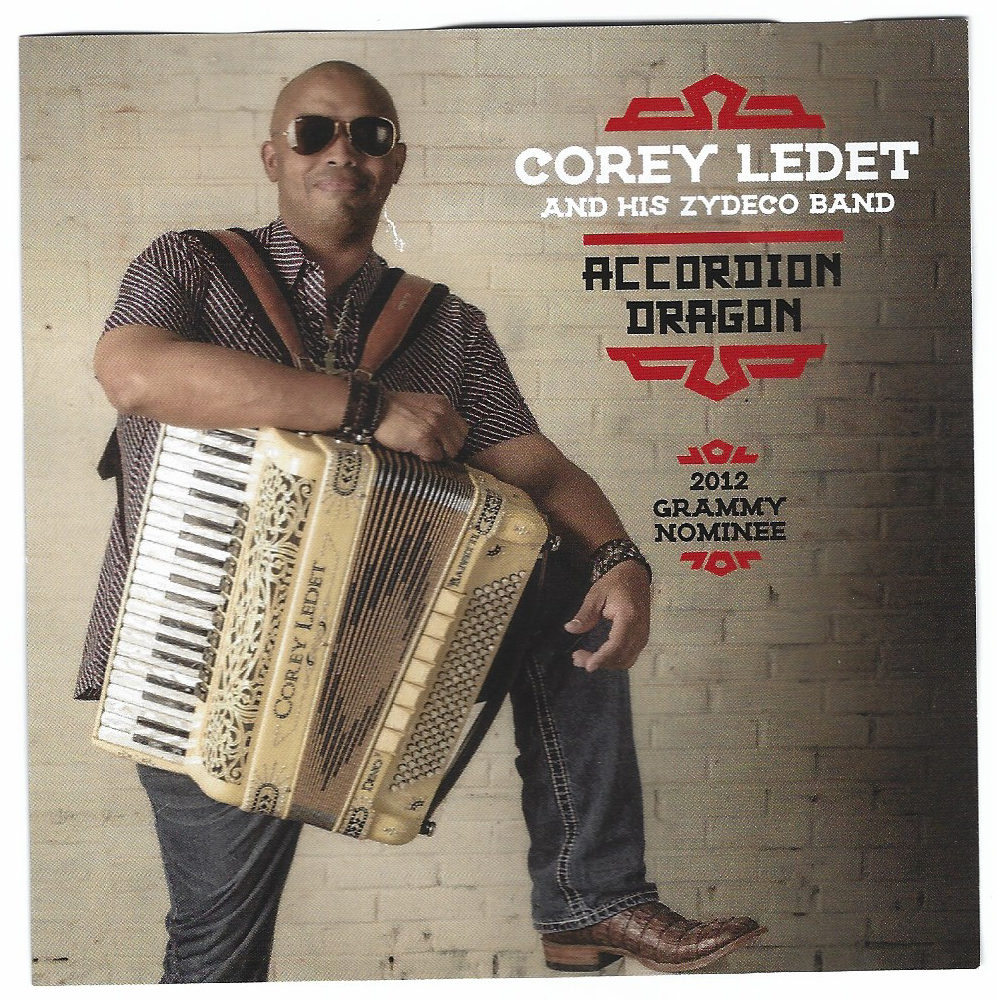

Corey Ledet can perform the entire range of such material, quite expertly, as heard on his new, all-original album Accordion Dragon (coreyledet.com). New songs are welcome in zydeco because, like all genres, it is rife with familiar old standards that are over-performed and over-recorded. But the most impressive facet of Accordion Dragon is its spotlight on both the Grammy-nominated Ledet’s agile, inventive accordion work and the unique band arrangements that Ledet crafts to showcase his talent. On the instrumental “Erika Potier’s Waltz,” for example, Ledet’s deft, ornate playing is underpinned with a bass line so increasingly complex that at times it resembles a solo. In addition this song features lush, urbane horn arrangements that are rarely heard on zydeco waltzes but which work quite well. The up-tempo “Dragon’s Boogie” and the slow, sensual “Dragon’s Blues” both refer to Ledet’s interest in martial arts, of which the dragon is a widely recognized symbol; in a bigger sense and in musical terms these songs honor the undiminished influence of Clifton Chenier, some three decades after his death. Such homage is quite natural and appropriate, because Corey Ledet stands tall among Chenier’s worthy torch-bearers.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based writer, folklorist, producer, and the former drummer for the Grammy-nominated Cajun/Western swing band The Hackberry Ramblers. Sandmel’s published work includes Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans (erniekdoebook.com). In May 2018, the LEH honored Sandmel with an award for his Lifetime Contributions to the Humanities.