Fall 2024

Looking Down and Back

The history and preservation of New Orleans’s ceramic street tiles

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

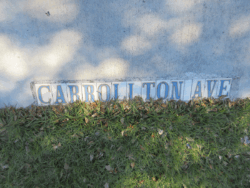

Street tiles on Carrollton Avenue in New Orleans.

Infrogmation, Wikimedia Commons

The iconic blue and white New Orleans street tiles are one of the “great untold stories” of the city, according to Ann Marie Guidry-Derby, co-owner of local ceramics shop Derby Pottery and Tile.

Yet, the city’s celebrated tile street markers are in danger of becoming just another fragment of the past. In fact, the historic tiles were even named to the Louisiana Landmarks Society’s most endangered list in 2022.

This is mainly due to a huge, much-needed citywide infrastructure project repairing cracked sidewalks and damaged streets. The city asks their street contractors to remove the tiles and reinsert them after new sidewalk is poured.

But that doesn’t always happen. And the street tiles are disappearing at an alarming rate.

Over the years, these blue and white tiles have become symbols of the city—so much so that local shops sell refrigerator magnets, keychains, T-shirts, and other souvenirs incorporating the beloved style. Even the corridors of New Orleans City Hall are lined with replicas of the iconic street tiles. Other US cities had ceramic street tiles in their developing neighborhoods, Guidry-Derby noted, but nowhere as widespread as the Crescent City.

Local amateur historian Michael Styborski has spent hours tracking down the tiles and their story. Styborski, an artist and photographer who admits his interest in the street tiles might be called an obsession, moved here with his family in 1977 and became fascinated with the tiles as a teenager. In the early 2000s, he started looking more deeply into where the tiles came from; over the subsequent nineteen years he has collected materials and tried to put together the whole puzzle. Some of the information he’s gathered could be called circumstantial evidence, and some of the dates may not be exact, but it’s as close as anyone has come to finding the hidden history of the historic street tiles. He has even visited the site of the factory in Zanesville, Ohio, that produced many of the tiles in the early 1900s.

Amazingly enough, it all started with a love story, according to Styborski, and corroborated by newspaper accounts. Belgian entrepreneur Prosper Lamal ran the Belgian exhibit at the 1884 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans. Lamal promoted Belgian products at expositions like this all over the world, and the enterprising businessman would have gone onto another world’s fair and sold more products—except he met the lovely Marie Grandmont, a sales clerk at D. H. Holmes department store. They married, and Lamal decided to make his permanent home in the city.

One of the Belgian products Lamal imported was street tile from Belgian Encaustic Tile Co. Encaustic is the name of a ceramic technique dating back to medieval times in which colored clay is inlaid into a contrasting-colored body.

In late 1800s New Orleans, the installation of sidewalks had become more common, said Styborski. Initially, private contractors putting down sidewalks would install street name tiles, as well as house number tiles, to provide added value to homeowners. The City of New Orleans started laying sidewalks when, in 1903, the United States Post Office stipulated that streets must have sidewalks of wood or concrete.

When Lamal died in 1895 in New Orleans, there were probably some surplus Belgian tiles, according to Styborski, but at some point contractors and the city started using tiles made at American Encaustic Tile Co. in Zanesville, Ohio, until the plant closed in 1935. Styborski has painstakingly documented the different types of tiles in the city. According to his unpublished 2021 field guide, there are five variations of the Belgian tiles and two variations of the American tiles in New Orleans.

What happened after the American plant closed? It’s anyone’s guess, Styborski says, but he has found evidence that the tiles were still placed in the 1960s and ’70s. The years from 1894 to 1930 were the heyday of the tiles installed because of street name changes. The tiles were mostly neglected after 1935 until local artisan Mark Derby became interested in the tiles as a side project in the early 2000s.

“The street tiles were interesting to me as a potter. Where they came from, how they stayed, and so on,” said Derby. After Hurricane Katrina devastated so much of the city, Derby had an epiphany that his side project was a way that he could help the city: “This was in my wheelhouse.”

Derby started by recreating the street tiles. Over two years, he made pencil rubbings of the whole alphabet in the American style, which has a yellow pinstripe groove around each letter.

The process to create the tiles by hand, the “old school way,” takes at least three days and involves pouring the colored clay into his handmade mold, drying the clay, firing the clay. “The heating process brings out the color and makes the tiles durable and impervious to water,” said Derby.

The humble artisan has made at least 29,000 individual tiles for the city to replace damaged or lost ones since 2006. “This was my way to give back,” said Derby. Derby Tiles is approved by the city as a street name tile vendor aligned with the city’s mission to “minimize harm to historic resources,” according to the Roadwork NOLA website.

“The City’s efforts to preserve tiles and other streetscape features are tied to the [guidelines] required by FEMA on federally funded roadwork projects. This includes roadwork projects under the Joint Infrastructure Recovery Request (JIRR),” said city Historic Preservation Specialist Philip Gilmore.

The JIRR, with almost $2.5 billion in federal funding to settle outstanding federal relief claims from widespread Katrina damage, started in early 2019 and mandated hiring a preservationist (Gilmore) and an archeologist to monitor the project and advise the city on how to avoid damaging the historic streetscapes, including the street tiles. As of January 2022, contractors can be fined $10,000 for loss, damage, or destruction of an existing street tile, said Gilmore.

Residents like Guidry and Styborski and others monitor—and even count—the street tiles in the city. In 2021 Styborski created a map to show how many tiles are in the city by neighborhood. Initially he walked the streets to map the tiles, but it proved too time consuming. Styborski eventually realized that Google Street View could show him every street corner in the city. The project still took him six months. Guidry and others also joined the crusade to identify locations where tiles are missing or improperly replaced. Aided by the city, this citizen-led effort, which also includes a Facebook group called Legacy Street Furniture of New Orleans, is trying to stop the loss of this important piece of New Orleans history.

“The craftsmanship, the detail, the beauty of these tiles mark a place in time,” Guidry said.

Harriet Riley is a freelance nonfiction writer living in New Orleans. She has taught both creative writing and journalism, worked as a non-profit director and as a newspaper reporter. Riley recently published articles in Mississippi Folklife, Minerva Rising, and the Wanderlust anthology. She holds an MA in print journalism from UT Austin.