“New Orleans Threw a Party and Nobody Came”

The 1984 Louisiana World Exposition

Published: August 31, 2023

Last Updated: November 30, 2023

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Neptune and a mermaid greet visitors to the fair.

“The fragrance of the food, they say, wafts all the way out to the Gulf of Mexico,” Michael Demarest wrote in Time, in an article published on May 28, 1984. “The roar of the bands washes up the Mississippi to St. Louis, maybe. The soul, spirit, and stomach of the World’s Fair that started its six-month run in New Orleans a week ago is the city itself: brooding and flamboyant, raucous and urbane, devout and dissolute. The fair stirs together the razzmatazz of Mardi Gras, the harmony of New Orleans’ elegant old buildings and the French-Spanish-African-Italian-Irish-German-Creole-Cajun gumbo gusto of its everyday, every-night street life.”

By most accounts, it was a spectacular display of regional culture, complete with nightly concerts and fireworks displays. The Louisiana World Exposition heralded the transformation of a significant swath of New Orleans geography and helped to elevate the tourism industry to its current position as one of city’s top economic drivers.

But it was also an unmitigated financial disaster that left many contractors unpaid and became the subject of criminal investigations and national ridicule. Far fewer visitors turned out than expected, and the fair eked out its six-month run under the pall of fiscal troubles that consumed headlines and nearly forced an early closure. It was the only world’s fair to declare bankruptcy while the gates were still open.

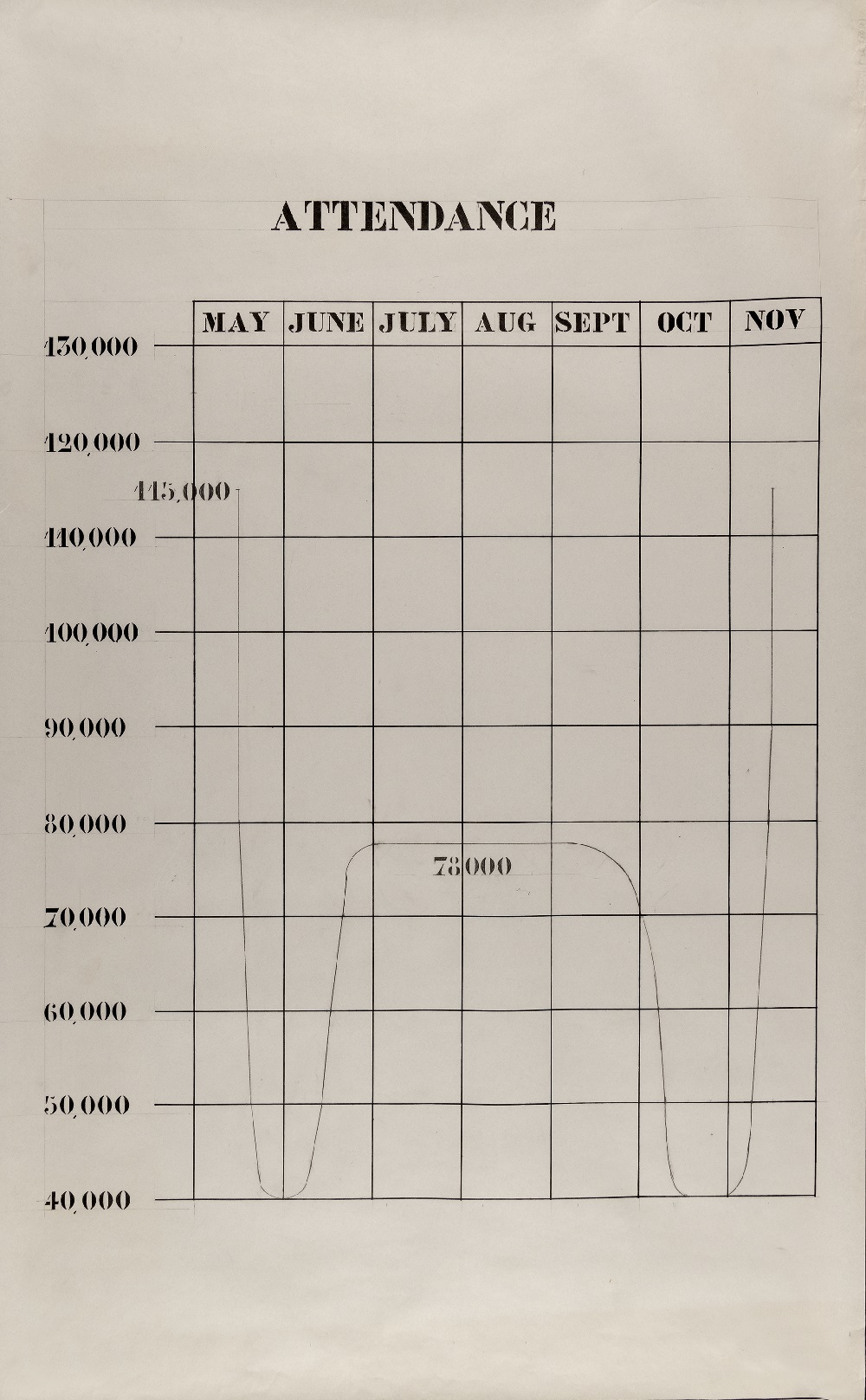

A final report graphs visitor numbers. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

An Event Decades in the Making

The fair opened its doors a century after the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition took over present-day Audubon Park in 1884. The twentieth-century version was based on an idea hatched in the 1960s, according to Tulane sociologist Kevin Fox Gotham, when a group of business leaders formed the Council for a Better Louisiana and conceived of such an event as a means of countering economic decline and attracting new investment to the region. Gotham observes in his 2007 book Authentic New Orleans: Tourism, Culture, and Race in the Big Easy that the Louisiana World Exposition was intended as “a major spectacle to revitalize the city and imbue social consensus in an era defined by fiscal crisis, racial upheaval, and metropolitan transformation.”

New Orleans was in tremendous flux in the years leading up to the 1984 world’s fair, as Gotham notes in a 2009 paper about the fair and its impacts. The city’s population dropped from 627,000 in 1960 to 557,000 in 1980, amid white flight and a precipitous drop in the oil and gas production upon which the state’s budget relied. The city was in financial crisis, and many leaders saw an event on the scale of a world’s fair as an appropriate antidote.

People with political and economic clout, including Governor Edwin Edwards and New Orleans developer Lester Kabacoff, owner of the Hilton Riverside hotel, threw their support behind the idea. The fair was envisioned as an opportunity to draw crowds to the city; to show off New Orleans culture; to get state and federal support for the construction of a new convention center that could attract larger events than the city was then able to host; and to revitalize a section of the city comprising largely derelict former warehouses once used by the shipping industry.

There was broad but not universal support for the idea. Gotham notes that Mayor Ernest “Dutch” Morial and Councilman Joseph Giarrusso (grandfather of the current New Orleans councilman of the same name) were among the skeptics.

The nonprofit Louisiana World Exposition Inc. was formed by business and civic leaders in 1976 as a public–private partnership tasked with planning and lining up financing for the fair. New Orleans was announced as the host for the fair in 1980, following approval by the US Secretary of Commerce and the Bureau of International Exhibitions, beating out Anchorage, Alaska, which had also filed a bid to host the 1984 exposition.

Pelicans and pineapples festoon a welcome gate. Photo by N. Thomas Criar, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Great Expectations

The fair opened on May 12, 1984, with Governor Edwards announcing, “Laissez les bons temps rouler!” In homage to the Mississippi flowing along the fair’s periphery, the official theme was “The World of Rivers: Fresh Water as a Source of Life.” A looming sculpture of Neptune greeted visitors at the main entrance, alongside, as Demarest described it to the readers of Time, “a titanic pair of bare-breasted mermaids, who have stirred a surprising flap in a city sated with live mammary display.”

Along the four thousand feet of riverfront newly opened up to the public, “[t]he grounds inside sparkle with fountains, winding waterways, aqueducts, pools and water sculptures,” wrote Demarest. “This is officially a World Exposition, on the scale of the one in Knoxville, Tenn., two years ago. Alongside that effort, New Orleans can hold its candle proudly, and with a raffish wink that few cities would wish to match.”

“I remember it being hot and muggy,” Bill Cotter told me. Cotter is a Los Angeles–based world’s fair enthusiast who attended the New Orleans fair in his early thirties and wrote a 2009 book about the exposition called The 1984 World’s Fair. “I remember wishing the site had more greenery on it,” he continued. “But what I also remember was just a big party atmosphere. A Mardi Gras that just went on night after night.”

“Music is everywhere,” Demarest wrote. “Cajun, zydeco and cool blues vie with big bands and hot jazz. There are marching bands and washboard scratchers, as well as beer hall oom-pah-pah and big-name oomph. Concert performers will run the scale from Willie Nelson and Linda Ronstadt to Itzhak Perlman and Isaac Stern. Naturally, Al Hirt and Pete Fountain will also drop by to blow a few notes on behalf of the local talent.”

The fair was a beloved pastime of many locals during its run, the backdrop to birthday parties, engagements, and even weddings. One poll found that two-thirds of the adults surveyed in Orleans, Jefferson, and St. Tammany Parishes attended the event. Cotter said so many bought season passes that the fair lost money on them. My own sixty-eight-year-old uncle still has his laminated fair pass; he remembers watching Kool and the Gang perform at the fair’s riverfront amphitheater, designed by the architect Frank Gehry.

Matt Gresham, 49, a Thibodaux native, told me the fair acted as his babysitter in the summer of 1984, thanks to relatives who lived in New Orleans. “We went at least once a week, if not more,” said Gresham. Video footage of him enjoying the fair alongside its pelican mascot Seymour D. Fair ended up in a fair commercial. His summer at the fair was a formative experience, representing the most time he’d ever spent on the riverfront. Today, Gresham works for the Port of New Orleans.

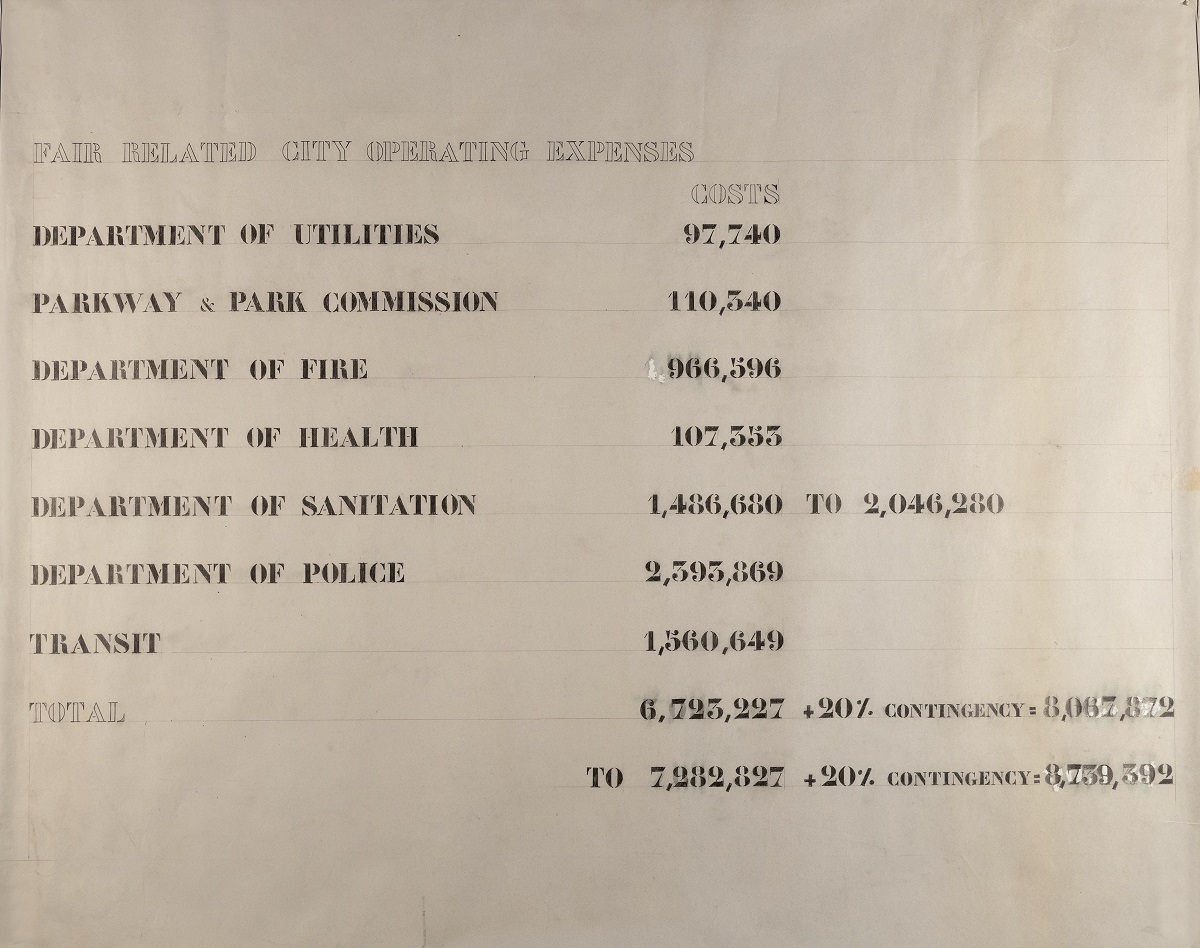

Final City of New Orleans expenses for the fair. The Historic New Orlean Collection.

Problems Apparent Early On

But the out-of-town markets proved harder to attract, and from the start, attendance at the fair fell far short of expectations.

To break even, the fair was counting on an average daily attendance of 65,000. Less than half of that showed up on the second day. “Attendance was sluggish all summer, to pick up only in the last month,” graduate student Peter Hagan wrote in his 1994 paper “The History and Impact of the 1984 Louisiana World Exposition.” By its close, the fair tallied around 9.2 million customers, according to the New York Times, around 44 percent shy of projections.

“For the first time, New Orleans threw a party and nobody came,” the Times-Picayune pronounced.

Part of the problem was timing. The fair coincided with an oil bust that took hold in the early part of the decade; the bust hit not only the Louisiana economy but also those of neighboring states like Texas. Jeanne Nathan, who’d served as the fair’s director of public relations, reflected that “Texas was the heart and soul” of the fair’s marketing base. “If you don’t have Texas,” Nathan said, “you’re in trouble.”

The 1984 Summer Olympics, held in Los Angeles during the fair’s run, also didn’t help. “They were gobbling up all the ad dollars,” Nathan said. “The advertisers who wanted to promote their cars and the like were fulfilling their marketing needs with the Olympics, which was a much more proven entity.”

The New Orleans fair came right on the heels of the 1982 fair, in Knoxville, Tennessee. That fair, too, fell shy of anticipated attendance, attracting just 11 million ticket-buyers, according to Gotham. (By comparison, he noted, the 1967 fair in Montreal boasted 50 million-plus participants, and the 1968 fair in San Antonio drew 64 million.) The market may have also been impacted by the 1982 opening of Walt Disney World’s Epcot Center, which was promoted, according to Cotter, as a “permanent world’s fair.”

Exacerbating the fair’s financial woes was the decision by the federal government to substantially reduce the subsidy typically offered for the event. In 1981 the Reagan administration let organizers know that just $10 million in federal support would be available for the New Orleans fair—half of what had been allocated for the Knoxville fair, according to Gotham. The president also bucked tradition and declined to attend the fair’s opening ceremonies.

Several multimillion-dollar loans were required to keep the gates open for the full run of show. By the time the gates closed for the last time, the Louisiana World Exposition was at least $100 million in the red. More than one hundred guarantors of a $40 million loan that made the fair possible lost their money, according to Hagan, and the state was on the hook for $20 million, to say nothing of local contractors and tradesmen, some of whom lost exorbitant sums. “We’re owed $17 million and we’re a relatively small group,” Jim Landis of Landis Construction Company told the New York Times in November 1984. An Associated Press article in December of that year cited court records showing total fair losses of around $121 million. Bankruptcy proceedings continued until 1993, according to Hagan, with some creditors paid “as little as eight cents on the dollar.”

“By the time the last note from a closing parade had echoed and died over the Mississippi in what in some respects seemed like a New Orleans wake, the fair’s turnstiles had clicked more than seven million times,” the New York Times reported in an article headlined “Failed fair gives New Orleans a painful hangover.” The article described sparse crowds, last-minute personnel shakeups, and “two grand jury inquiries and a Federal Bureau of Investigation operation to trace kickbacks.” According to Cotter, litigation stretched for as long as twenty years after the gates closed, with no convictions.

Nathan argued that it was a piling-on by local and national news outlets eager to make news of the fair’s financial troubles as much as the lagging public and private financing that doomed the 1984 fair.

“You could call this a media catastrophe,” Nathan told me. “We are being characterized as a failure every single day on the front page of the Times-Picayune,” she said, remembering a recurring graphic in the local paper tallying the projected fair attendance alongside actual crowd sizes.

“I’d say it was a disaster in a public image sort way,” Cotter agreed. “When it goes in the paper that the bathrooms aren’t being cleaned and the janitors aren’t being paid, that never looks good for a host city.” On the other hand, Cotter said, “it lost money but almost every single one does.” He noted that the Knoxville fair also came very close to declaring bankruptcy.

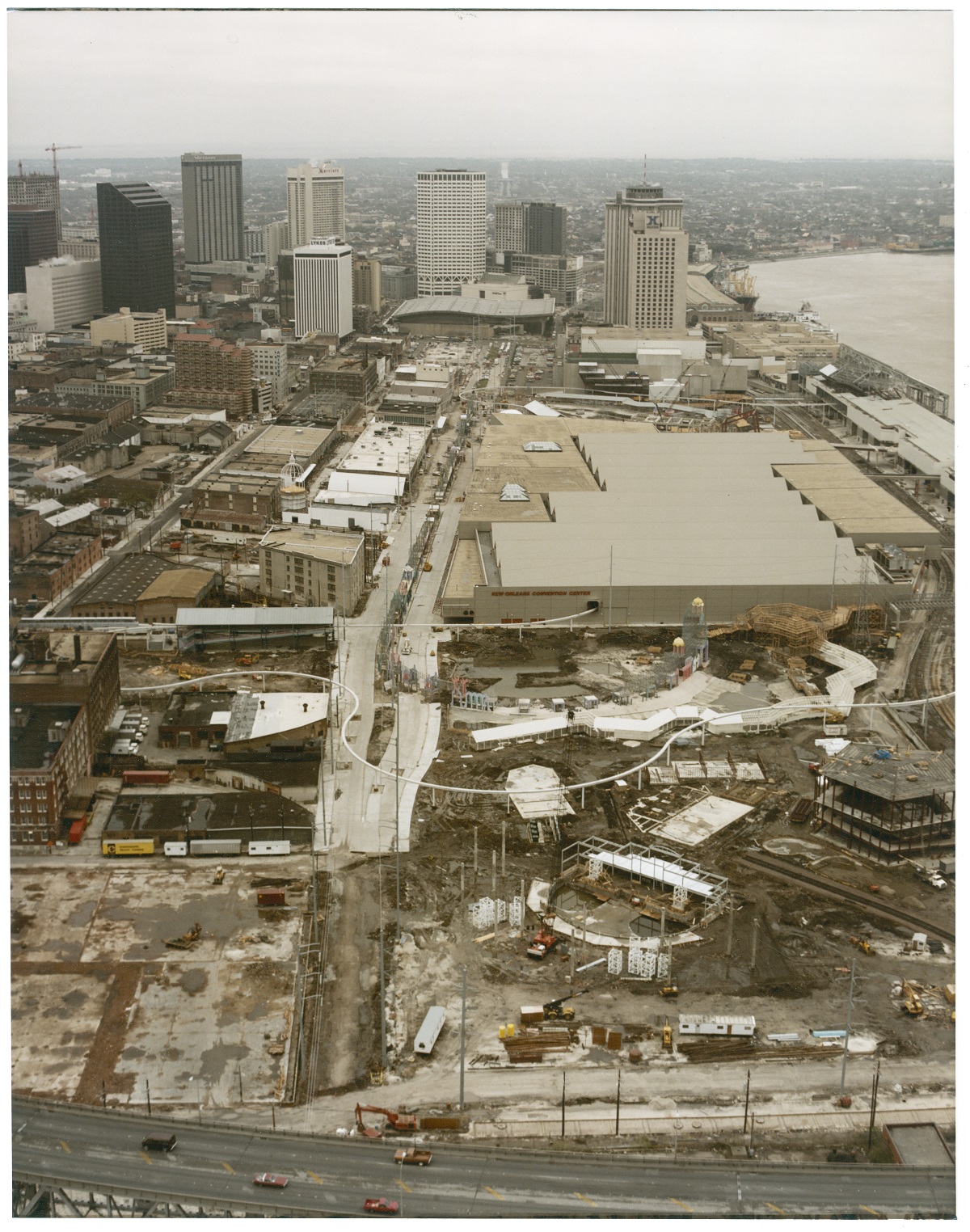

An aerial view of development, ca. 1984. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Birth of the Warehouse District and the Modern Tourism Industry

Historically, Cotter said, world’s fairs have been hosted by countries and cities looking to position themselves as leaders in some realm or to otherwise put themselves on the map.

“These fairs are not done because somebody wakes up and says, ‘Let’s go entertain people,’” he said. In the case of New Orleans, the municipal interests were to redevelop a largely fallow former industrial section of the city and home in on the tourism sector.

“The world’s fair was one of the great shows and experiences,” said developer Pres Kabacoff, 77, who with his father, the late Lester Kabacoff, was intimately involved in bringing the fair to the city. “It was a dismal failure at the box office for a whole number of reasons, but it also helped to revive one of the great neighborhoods in the country.”

Kabacoff told me he was tasked with assembling the eighty-plus acres of parcels for the fair in the largely derelict section of town not yet known as the Warehouse District. He became convinced that the area—with its proximity to the river, French Quarter, and Central Business District, and the charm of its old structures with exposed brick walls and huge windows—was prime for a residential neighborhood. (When I asked him what the area was called at the time, he said, “All I remember is, Don’t call Gus, he’ll cuss for all of us”—a bit of graffiti scrawled on one of the abandoned buildings.)

At the time, Kabacoff said, the idea of turning warehouses into other uses was still nascent in this country, limited to the SoHo neighborhood in lower Manhattan and Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco. “The notion was if you put a world’s fair there, you’d get enough improvements in the area to generate a new use of the neighborhood,” he said.

During the fair, Kabacoff leased the Federal Fibre Mills building, a 150,000-square-foot warehouse that contained the maintenance facility for the monorail system that ferried passengers around the fairgrounds, a popular beer garden, and a Cajun dance hall, among other amenities. At the close of the fair, Kabacoff and his business partner, the late Ed Boettner, bought the building and, relying on a combination of historic and affordable housing tax credits to help finance the development, turned it into the first warehouse-to-residential project in the neighborhood through their new company Historic Restoration, Inc., now known as HRI Properties.

The fair also left lasting impacts on the city’s tourism economy. Although New Orleans was famous for its celebratory spirit, and the French Quarter and Mardi Gras were huge tourist draws, the city had not managed to develop a steady year-round tourism base as of the 1970s, according to Cotter.

“The infrastructure simply was not there to support a significant convention trade or to attract families interested in seeing the city or the rest of Louisiana,” Cotter wrote. The exposition would make possible the construction of a new $88 million convention center, with the fair planned as its first tenant.

“It really was a catalyst for New Orleans being awakened as an international destination,” said Mark Romig, who served as the exposition’s director of protocol and guest relations. Today Romig is senior vice president and chief marketing officer for New Orleans and Company, which markets the city to travelers. “It pushed us twenty years faster than I think we would have gone.”

The fair not only resulted in the completion of the first phase of the city’s new convention center—now one of the largest in the country. By Gotham’s count, it was also responsible for the construction of some ten thousand hotel rooms by companies including Westin, Windsor Court, Holiday Inn, and Sheraton. The Riverwalk Mall, a tourist-oriented riverfront shopping center built by the James Rouse company, took shape as a result of the fair. And the fair’s International Riverfront building would become the Julia Street cruise terminal.

“By the 1990s, a proliferation of tourism attractions and entertaining spectacles meant New Orleans residents were now living in a metropolitan area reconfigured as interesting, entertaining, and attractive for tourists,” Gotham writes. Tourism is now arguably the city’s top industry, with a peak of 19 million visitors in 2019 spending more than $10 billion, according to Romig.

A view from the Mississippi Aerial River Transit (MART). Photo by N. Thomas Criar, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Still, the benefits resulting from changes to the city’s physical and economic landscapes were not universally accessible. “Critics argued that the exposition’s residual products—such as riverfront development and reinvestment in the Warehouse District—did little to address wider social problems, including neighborhood disinvestment and racial polarization,” Gotham writes. “[E]xposition attractions and other tourism developments seemed increasingly divorced from the problems and concerns of the city’s neighborhoods and working people.”

The 1984 Louisiana Exposition was the last world’s fair held in the United States. Shortly after its close, Harry Greenberger, then president of the French Quarter Business Association, told the New York Times, “You can go to Disney World. You can go to Epcot. What world expositions used to be were the leading edge of the newest ideas and the newest technology. Now we see that every day on television.”

According to the New York Times, among the smaller-than-desired crowd in the closing days of the 1984 fair was the general manager of the fair being planned for Chicago in 1992. That fair never materialized, with New Orleans held up as a cautionary tale.

Emilie Bahr is a writer and urban planner living in New Orleans. She can be reached at [email protected].